Fifty Year Friday: Byrds, Hollies and Buffalo Springfield

Formed in 1964, in Los Angeles California, the Byrds are generally, with the advantage of retrospect, considered one of the more essential and influential bands of the mid-sixties, primarily due to their blending the rock style of the British Invasion with elements of country and western music, folk, west coast rock and psychedelia.

The fourth album, opens robustly with the semi-ironic, partly humorous, “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” Other strong songs include the jingly-jangly arranged Chris Hillman composition “Have You Seen Her Face”, Hillman’s “The Girl with No Name” (apparently inspired by a young lady with then real name of “Girl Freiberg”, one of the better known covers of Bob Dylan’s “My Back Pages”, and the David Crosby tracks “”Renaissance Fair” , “Everybody’s Been Burned”, “Mind Gardens” and “Why.” Psychedelia and Indian musical influences are present on several tracks with an electronic oscillator providing suitable effects and McGuinn’s guitar providing a suitable substitute for the sitar on “Why.”

Track listing [from Wikipedia]

Side one

- “So You Want to Be a Rock ‘n’ Roll Star” (Jim McGuinn, Chris Hillman) – 2:05

- “Have You Seen Her Face” (Chris Hillman) – 2:25

- “C.T.A.-102” (Jim McGuinn, Robert J. Hippard) – 2:28

- “Renaissance Fair” (David Crosby, Jim McGuinn) – 1:51

- “Time Between” (Chris Hillman) – 1:53

- “Everybody’s Been Burned” (David Crosby) – 3:05

Side two

- “Thoughts and Words” (Chris Hillman) – 2:56

- “Mind Gardens” (David Crosby) – 3:28

- “My Back Pages” (Bob Dylan) – 3:08

- “The Girl with No Name” (Chris Hillman) – 1:50

- “Why” (Jim McGuinn, David Crosby) – 2:45

Personnel

Sources for this section are as follows:[1][5][23][54][55]

The Byrds

- Jim McGuinn – lead guitar, vocals

- David Crosby – rhythm guitar, vocals

- Chris Hillman – electric bass, vocals (acoustic guitar on bonus track 12)

- Michael Clarke – drums

The Hollies, released two albums in 1967, “Evolution” and “Butterfly”

Both albums have their annoying, overly-commercial, teeny-bop elements (think of what you dislike about Herman’s Hermits) but this is compensated by the inclusion of several excellent tracks. Lot of the credit for what is really good here goes to Graham Nash.

The best track on “Evolution” is the simply arranged and perfectly conceived “Stop Right There.” Other worthwhile tracks include the hyper-vibrato-infused “”Lullaby to Tim”, the catchy, if outdated-sounding for 1967, “Have You Ever Loved Somebody?”, the wistful, and melancholic “Rain on the Window”, the early Beatles-era “Heading for a Fall”, and the AM radio hit “Carrie Anne.”

US/Canada track listing of “Evolution” [from Wikipedia]

Side 1

- “Carrie Anne” (Clarke-Hicks-Nash) lead vocal: Clarke, Hicks and Nash

- “Stop Right There”

- “Rain on the Window”

- “Then the Heartaches Begin”

- “Ye Olde Toffee Shoppe”

Side 2

- “You Need Love”

- “Heading for a Fall”

- “The Games We Play”

- “Lullaby to Tim”

- “Have You Ever Loved Somebody”

Personnel

- Allan Clarke – vocals, harmonica

- Tony Hicks – lead guitar, vocals

- Graham Nash – rhythm guitar, vocals

- Bobby Elliott – drums

- Bernie Calvert – bass guitar

“Butterfly” (retitled “Dear Eloise / King Midas in Reverse” in the US) has its moments also such as the introduction to “Eloise”, the upbeat, yet also partly annoyingly cloying “Wishyouawish” and “Away Away Away”, Nash’s simple and direct “Butterfly” (similar to “Stop Right There” on “Evolution”), and “Leave Me”, which was on the original twelve track UK “Evolution” album but not on the US ten track release of “Evolution.” Another notable track, not on the UK version, but only on the US version of the “Butterfly” LP, is the quirky, “King Midas with a Curse.”

US/Canada track listing of “Butterfly” released as “Dear Eloise / King Midas in Reverse” [from Wikipedia]

Side 1

- “Dear Eloise”

- “Wishyouawish”

- “Charlie and Fred”

- “Butterfly”

- “Leave Me” (Clarke-Hicks-Nash)

- “Postcard”

Side 2

- “King Midas in Reverse“

- “Would You Believe?”

- “Away Away Away”

- “Maker”

- “Step Inside”

Personnel

- Allan Clarke – vocals, harmonica

- Tony Hicks – lead guitar, vocals

- Graham Nash – rhythm guitar, vocals

- Bobby Elliott – drums

- Bernie Calvert – bass guitar

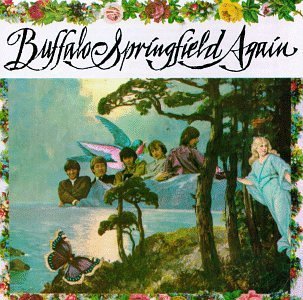

At this point the reader probably sees where I am going with this post — covering the Byrds, which had David Crosby writing some of their best songs, the Hollies, with Graham Nash writing some of their best tunes, and next, Buffalo Springfield, with Neil Young and Stephen Stills — these four guitarists/singers/composers forming Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

Buffalo Springfield’s first album. simply titled after the band, was released in December 1966, but it qualifies as one of the first solidly 1967-sounding albums. In January 1967, the most impressive song of the first half of 1967 hit the airwaves, a rare objective view of the widening political divide in the U.S.. “For What It’s Worth”. I was eleven when I heard this, and it was, for me, clearly the coolest song on AM radio of all time. It is worth re-examaning the lyrics so relevant to 1967, but also applicable to today:

There’s a man with a gun over there

Telling me I got to beware.

Everybody look what’s going down.

Nobody’s right if everybody’s wrong.

Young people speaking their minds —

Getting so much resistance from behind.

Everybody look what’s going down.

A thousand people in the street

Singing songs and carrying signs

Mostly say hooray for our side!

Everybody look what’s going down.

Into your life it will creep.

It starts when you’re always afraid:

You step out of line, the man come and take you away.

Everybody look what’s going down.

Stop, hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down.

Stop, now, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down.

Stop, children, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down.

Track listing of “Buffalo Springfield” [from Wikipedia]

| March 1967 pressing side one | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

| 1. | “For What It’s Worth” (Dec. 5) | Stephen Stills | Steve with Richie & Dewey | 2:40 |

| 2. | “Go and Say Goodbye” (July 18) | Stephen Stills | Richie & Steve | 2:20 |

| 3. | “Sit Down, I Think I Love You” (August) | Stephen Stills | Richie and Steve | 2:30 |

| 4. | “Nowadays Clancy Can’t Even Sing” (July 18) | Neil Young | Richie with Steve and Neil | 3:24 |

| 5. | “Hot Dusty Roads” (August) | Stephen Stills | Steve with Richie | 2:47 |

| 6. | “Everybody’s Wrong” (August) | Stephen Stills | Richie with Steve and Neil | 2:25 |

| March 1967 pressing side two | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

| 1. | “Flying on the Ground Is Wrong” (September 10) | Neil Young | Richie with Steve and Neil | 2:40 |

| 2. | “Burned” (August) | Neil Young | Neil with Richie and Steve | 2:15 |

| 3. | “Do I Have to Come Right Out and Say It” (August) | Neil Young | Richie with Steve and Neil | 3:04 |

| 4. | “Leave” (August) | Stephen Stills | Steve with Richie | 2:42 |

| 5. | “Out of My Mind” (August) | Neil Young | Neil with Richie and Steve | 3:06 |

| 6. | “Pay the Price” (August) | Stephen Stills | Steve with Richie | 2:36 |

Personnel

- Buffalo Springfield

- Stephen Stills — vocals, guitars, keyboards

- Neil Young — vocals, guitars, harmonica, piano

- Richie Furay — vocals, rhythm guitar

- Bruce Palmer — bass guitar

- Dewey Martin — drums, backing vocals

Track listing [from Wikipedia]

| Side one | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

| 1. | “Mr. Soul“ | Neil Young | Neil with Richie and Steve | 2:49 |

| 2. | “A Child’s Claim to Fame” | Richie Furay | Richie with Steve and Neil | 2:09 |

| 3. | “Everydays” | Stephen Stills | Steve with Richie | 2:40 |

| 4. | “Expecting to Fly“ | Neil Young | Neil | 3:43 |

| 5. | “Bluebird” | Stephen Stills | Steve and Richie | 4:28 |

| Side two | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Vocals | Length |

| 1. | “Hung Upside Down” | Stephen Stills | Richie and Steve with Neil and Richie | 3:27 |

| 2. | “Sad Memory” | Richie Furay | Richie | 3:01 |

| 3. | “Good Time Boy” | Richie Furay | Dewey | 2:14 |

| 4. | “Rock and Roll Woman” | Stephen Stills | Steve with Richie and Neil | 2:46 |

| 5. | “Broken Arrow“ | Neil Young | Neil and Richie | 6:14 |

Personnel

- Buffalo Springfield

- Stephen Stills — vocals, guitars, keyboards

- Neil Young — vocals, guitars

- Richie Furay — vocals, rhythm guitar

- Bruce Palmer — bass guitar

- Dewey Martin — vocals, drums

- Additional personnel

- James Burton — dobro on “A Child’s Claim to Fame”

- Chris Sarns — guitar on “Broken Arrow”

- Charlie Chin — banjo on “Bluebird”

- Jack Nitzsche — electric piano on “Expecting to Fly”

- Don Randi — piano on “Expecting to Fly” and “Broken Arrow”

- Jim Fielder — bass on “Everydays”

- Bobby West — bass on “Bluebird”

- The American Soul Train — horn section on “Good Time Boy”

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(40)/discogs-images/R-762405-1156303154.jpeg.jpg)

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1246114-1304100058.jpeg.jpg)