Fifty Year Friday: November 1970

If you were creating a bracket for “Top Sixteen” best months for rock album releases, November of 1970 would not only be included but possibly end up as the winner depending on the diversity of your musical taste in the many rock genres of the early 1970s. For me, it is a particularly special month with debut albums by two of my all-time favorite rock groups, Gentle Giant and Emerson, Lake and Palmer, and notably, not rock nor prog nor jazz, the release of Joshua Rifkin’s first Scott Joplin album.

Joshua Rifkin: Scott Joplin Piano Rags

Started in the mid-sixties, Nonesuch Records was a budget classical label — and when I mean budget, this applied to both the price and the quality of the pressings, which generally had more than their share of vinyl surface noise. However, with focus on releasing lesser known music and generally solid, if not exceptional performances, Nonesuch releases were not only welcome by individual music record buyers but by record libraries, both community and college/university libraries. Music ranged from Medieval and Renaissance to Mannheim school composers to Berwald to Charles Ives to contemporary composers with electronic music by Subotnick and a 2 LP guide to electronic music. Nonesuch also launched the Explorer series which included music from India, Bulgaria and Japan. And then, in November of 1970, Nonesuch kicked off the ragtime revival by releasing Joshua Rifkin’s performances of the well-known “Maple Leaf Rag” and seven additional Scott Joplin gems, including “The Entertainer” which was eventually showcased in 1973 as the theme to the movie, The Sting.

What makes this album special is the care and musical attention Rifkin administers to each work, taking “The Entertainer”, for example, at a sensitive strolling tempo and stretching the lilting “Magnetic Rag” to over five minutes. Ragtime was now revived: not hurried through at a breakneck speed like some quirky novelty, but treated with the same respect as Chopin or Debussy — with record stores across Southern California generally filing this ragtime album in the classical music section. Fortunately Nonesuch and Joshua Rifkin were awarded for their efforts, with this album becoming the first Nonesuch album to sell one million copies.

Cat Stevens: Tea for the Tillerman

With his fourth album, Tea for the Tillerman, Cat Steven’s finely tunes the simplicity of his music and lyrics to create his very best work: an album without weakness or a moment of filler material. Two tracks, back to back on side one, are two of his very best ever: “Wild World”, which received plenty of FM airplay, and “Sad Lisa.”

David Bowie: Man Whole Sold the World

Whereas Tea for the Tillerman is an album of musical and lyrical transparent simplicity, David Bowie’s Man Who Sold the World, released in the U.S. on November 4, 1970, is a work of layered complexities. And though there is no apparent unity in the songs, it provides a musical experience approaching an art-music song cycle. I hadn’t heard this album in at least forty-five years and was not expecting it to provide much more than a trip down memory lane. I was also expecting it to be uneven with sections lacking in compelling musical interest. I was completely wrong and had underestimated the instrumental ingredients applied to each and every song on the album. To what degree producer Tony Viscounti deserves credit for the final product, I can only guess, but Bowie’s selection of him for a band member along with guitarist Mick Ronson and drummer Mick Woodmansey provided a solid framework for a varied and multi-faceted album.

This album also provides a more modern version of David Bowie: one where he starts to develop the persona and vocal characteristics that were perfected for Ziggy Stardust. Unlike most British rock singers up to this point, Bowie doesn’t shy away from emphasizing and exaggerating his English accent. That first step, provides an effective starting point for the idiosyncratic pitch, timbre, and inflection traits that became such an easily recognizable trademark in Bowie’s vocals. And in the midst of all the musical freshness, boldness, and complexity are lively lyrics as in same-sex encounter of “The Width of a Circle.” (Yes, with the seventies there was less interference by record executives around “appropriate content”, now allowing tracks like Steppenwolf 7’s (another album released in November of 1970) “Ball Crusher.”

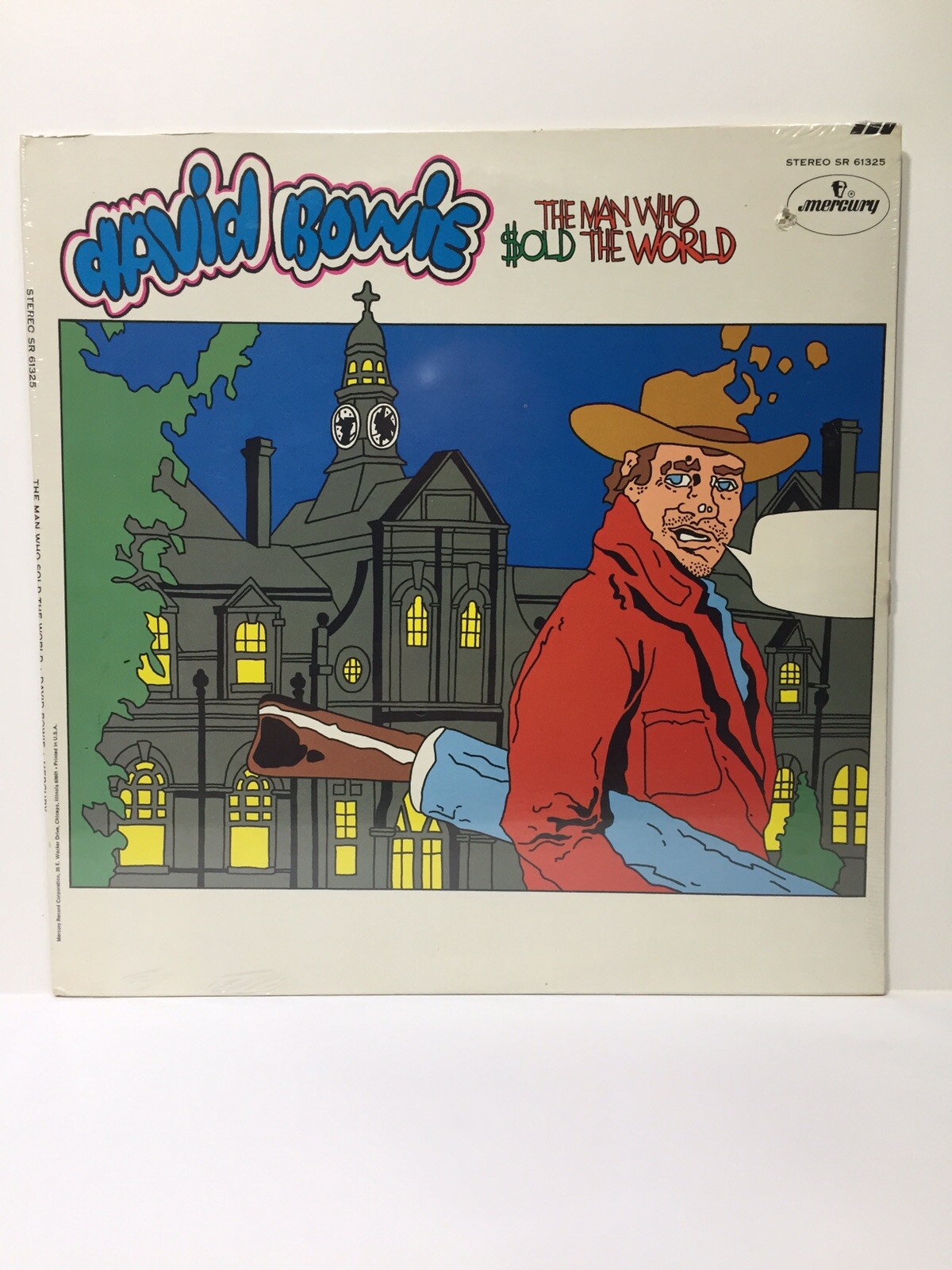

There is great musical variety throughout Man Who Sold the World from the effortlessly accessible T-Rex-influenced “Black Country Rock” to the hard-rock “Running Gun Blues” to more lyrical works like “After All” and “The Man Who Sold the World.” The album sold poorly in the U.S. and was pretty much forgotten until the solid success of Ziggy Stardust sparked a strong interest in earlier Bowie albums. The originally-intended cover created for the album, the comic-book like artwork of a man carrying a rifle against a backdrop of buildings and an open caption (for which the proposed multi-meaning content of “roll up your sleeves and show us your arms” was rejected and thus, by default, a blank caption bubble) was not to Bowie’s taste and he chose instead to have the cover shown above. Such a cover was determined unacceptable for U.S. release and the original artwork of the cowboy and blank caption bubble was used — shown below. The later U.S. release, after Ziggy became popular, used the cover shown below that.

Kinks: Lola Versus Powerman and the Moneygoround, Part One

Where Bowie represents the leading edge of London modernity, Ray Davies and the Kinks continue to represent more conservative values. Here we have another representation of the hard-working working-class culture extended into an album length-theme on the hard-working working-class-band-making-the-big-time contrasted against the greedy representatives of the record industry.

And yet, it is Ray Davies and the Kink’s “Lola”, not Bowie’s “Width of the Circle” that disintegrated conservative AM radio constraints. Sure Bowie was relatively unknown and the Kinks were long-time rock fixtures, but it was the ambiguity of “Lola” that allowed it to slip on to the pop-music airwaves; and that same ambiguity enhanced the overall coolness of the song and contributed to its popularity, particularly one of the coolest lyrics in rock: “Well, I’m not the world’s most masculine man, but I know what I am and I’m glad I’m a man, and so is Lola.” Ironically, the BBC forced the Kinks to overdub one word — but it was related to BBC’s policy on product promotion: Ray Davies was forced to overdub “Coca” with “Cherry” on the single-version of the song to avoid any semblance of advertising “Coca Cola.

Lola is the most notable song on this strong album, but there isn’t a bad track. Dave Davies provides two songs on this album including the beautiful ballad “Strangers”, which musically and lyrically is one of the most heartwarming songs in the Kink’s catalog, a sentimental tribute to the bond of two brothers. His other song, “Rats”, rocks hard and relentlessly pushes forward musically and lyrically. And of course, we have Ray Davies “back to nature” Apeman — catchy and quirky.

I had always wondered about the “Part One” in the title. Well, it turns out that this was originally planned as a double album, but the Kink’s released what they had with plans for a follow-up that never happened, despite indications that they had started on sequel material. At any rate, Part One stands perfectly well on its own, and works well as a concept album about the rise of an English rock band, having a number of biographical elements, and an abundance of musical charm.

Velvet Underground: Loaded

Based on direction from Atlantic Records, the Velvet Underground’s fourth album, Loaded, released November 1970, was primarily focused on including material suitable for singles with six of the ten songs in the 2 1/2 minute to 4 minute range. However, the album provided not even one single that created any kind of dent in either the UK or US charts, and the album itself also had little commercial success making no advance into the Billboard 200.

The combination of strong lyrics and easily assimilable music from the forlorn “Who loves the sun”, the classic “Sweet Jane”, to the autobiographical “Rock & Roll” to the album’s final and longest track “Oh! Sweet Nothin'” have served this album well with it’s influence on other bands and albums, including its apparent influence on Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust, and the album’s steady long-term increase in popularity. So much so, that there was a 2-CD release of the album in 1997 and a six-CD release in 2015. At least check out the bonus tracks via CD or a streaming service. One of the unreleased tracks, “Ride Into the Sun”, seems like it would have been perfect to have closed out the original LP.

Ike and Tina Turner: Workin’ Together

Some albums are soooo good that one doesn’t know where to start in praising them. However, in the case of “Workin’ Together”, a suitable follow-up title to their previous album, “Come Together”, one has to start and end with Tina Turner. She sings with incredible variety and virtuosity on this album, performing at the level of a top-tier jazz instrumentalist, a feat rarely accomplished except by such legends like Billie Holiday and Ella Fitzgerald. Pay particular attention to the melodic expression of her vocals on “The Way you Love Me” and “You Can Have It.” Then there’s the delight and energy of her rendition of Paul McCartney’s “Get Back” elevating it to Hall of Fame level. The instrumentation and arrangements on the album are excellent and one gets many bonuses like the intriguing piano solo on a revisited version of Jessie Hill’s 1960-hit “Ooh Poo Pah Doo” and Alline Bullock’s (older sister of Tina Turner) leading-edge, hard swinging example of 1970 funk, “Funkier Than a Mosquita’s Tweeter” which was put on the B side of the single of the album’s best known number, “Proud Mary.” So it’s easy to start any retrospective reflection on this classic album by focusing on Tina Turner’s contributions, understanding all the other work involved and realized so exceptionally well by Ike Turner, The Kings of Rhythm, and the Ikettes, but ultimately coming back to the most important factor, the contributions of Tina Turner.

Emerson, Lake and Palmer: Emerson Lake and Palmer

On November 20, 1970 (with no corresponding U.S. release until early in 1971) Emerson, Lake and Palmer released their self-titled first album. Even more heavily classically influenced than Emerson’s work with the Nice, the album was a delight for both fans of the revered and historically-important acoustic piano and the new, and not-yet-fully exploited Moog synthesizer. The other two members of Emerson’s newly formed trio, providing their own significant contributions, were Greg Lake, previously of King Crimson, and impressively-skilled relatively young drummer Carl Palmer previously with the Atomic Rooster.

The album opens most vigorously with a formidable arrangement of Bela Bartok’s solo piano piece “Allegro Barbaro”, transformed to fit the trio capabilities so impressively that anyone with any uncertainty about when progressive rock had truly proceeded beyond the psychedelic rock/ proto-prog stage, would have to concede that it happened at least with the release of this album. The reworking of the Bartok’s piano work into a prog-rock work is so complete and seamless that anyone not previously familiar with the work would have little reason not to identify this as some original masterpiece reflecting the aesthetics of the group and the turbulent times of the start of the 1970s. So passionately and comprehensively realized is the arrangement and performance that I consider it an indisputable improvement over the superb original.

Greg Lake provides the main melody and lyrics for the next track, “Take a Pebble” as he does for the more well-know final track, “Lucky Man.” In the instrumental section of “Take A Pebble”, Lake strums through a reflective guitar passage that effectively compliments Emerson’s extended solo piano work. The third track is an arrangement of the first movement of Leoš Janáček’s Sinfonietta. Once again we have an arrangement so complete it seems original, particularly with Lake’s and Fraser’s lyrics used in transforming the opening brass fanfare theme into a verse and then that material transformed further and more remotely into a chorus/bridge. The three main notes then are used as the basis for an instrumental interlude that then gives way to a Bach passage on a organ with a return to the verse and an synthetic sonic explosion (replaced in the remastered version with the original coda.)

The second side opens up with formidable Emerson composition “Three Fates”. The first represented Fate, Clotho, is realized on the Royal Festival Hall’s grand pipe organ, the second Fate, Lachesis, is realized as a grand piano solo and then the third fate, Atropos, after a brief return to the pipe organ, is launched in scintillating syncopated 7/8 with the piece wrapped up with an another synthetic explosion possibly representing the cutting of the thread.

“Tank” proceeds at full steam, a perfect platform for Carl Palmer, starting off as a trio featuring a sparkling clavinet and then after Palmer and Emerson trading twos and a brief transitional passage includes one of the most engaging and musical drum solos of 1970s rock followed by an musical onslaught that features exhilarating Moog synthesizer work by Emerson.

The album ends with Lake’s “Lucky Man” very much in the folk-rock vein with solid acoustic, electric and bass work from Lake and then the electrically charged Moog to end the song and the album. Released as a single, “Lucky Man” mostly got its airplay on FM and in Europe until picking up some traction in 1971 on AM radio and then again in 1973. Interestingly, this is the one song that did the best, commercially (and financially through royalties) for ELP — this simple four-chord (I, V, ii, vi) based song Greg Lake wrote around the age of 12. This 1970 realization of a pretty solid and easily accessible song eventually provided relatively wide appeal, something that, despite their progressive focus, Emerson, Lake and Palmer were also able to achieve as a trio in the following years after the release of this excellent album.

Gentle Giant: Gentle Giant

Gentle Giant’s self-titled first album was released in the UK on November 22, 1970. (It was not released in the U.S. until several years later.) Though far short of their next six albums, there is a lot of strong musical content on the album.

Gentle Giant, was formed by the Shulman brothers, Derek, Phil and Ray, after the demise of their previous group, Simon Dupree and the Big Sound. Bringing along their previous drummer, they auditioned several candidates for keyboards, apparently one of them Elton John, and auditioned candidates for the lead guitarist. The keyboardist would be Kerry Minnear, their most important and distinctive acquisition due to his compositional contributions. They also did well in landing semi-professional blues guitarist Gary Green, who was one of the more underrated guitarists of the seventies.

This first album starts and ends with some weaknesses including some silly lyrics in the opening track and the penultimate track (the last track is a brief instrumental, a short rendition of “God Save the Queen.”) The same goes with some of the music on those tracks, but when one sets that aside, the album goes beyond providing musical insight into the future Gentle Giant, delivering an album that is pretty good for its own sake.

First off, one must acknowledge that this album is not much more than a collection of well-executed, intriguing songs with no apparent attempt a unifying the album or providing musical continuity beyond a recurring synthesizer motive (derived from the third song) that sneaks its way back between later tracks.

The first track may be the weakest, and even cringe-worthy, but Minnear’s organ work is exemplary, Ray Shulman’s bass work is admirably accomplished, the band’s playing is remarkably tight (all instruments are played by the band members including the featured trumpet), and both the incorporation and the execution of the time signature changes maintains listener-interest throughout. The instrumental passage in the middle is the highlight, presaging later work, and includes a fine choral-like section. The return to the main theme may be somewhat predictable, but it sets up the perfect contrast for the intro of the second track.

That second track, “Funny Ways”, is arguably the finest song in the set. The opening strummed guitar, cello, and violin give away to guitar and vocals and then the perfectly-placed pizzicato violin. Once again, it is Gentle Giant playing all the instruments — as always the case for their albums. The chorus is short but noteworthy displaying Gentle Giant’s penchant for musically supporting the text, with “My ways are strange” preceded by a g-minor-seventh motif with equivalent chord changes on the underlying bass notes and gives quickly to another verse and the accompanying strings. This then is followed by a return of the chorus and a contrasting sort of bridge-like section that provides opportunity for one of Gentle Giant’s most notable trademarks, the use of short-phrase repetition — a short, often quirky fragment that is played four times often with subtle changes underneath. Gary Green provides front-and-center electric guitar with accompanying trumpet punctuation until a return to the verse which winds the song down nicely, eschewing any chorus repeat. Fortunately for their fans that attended live performances, this song was included in their concerts up through their eighth album.

The third track, “Alucard”, starts with an upbeat bebop-based approach that is followed by a short motivic interplay that uses the time-tested centuries-old technique of shortening a repeated musical phrase, an oft-used Gentle Giant trademark. Minnear lets loose with synthesizer at full-power, followed by a tasteful dramatic section that evolves into a moog-lead sequence that I always think of as the Gentle Giant “stride style” — not because it resembles stride music in any-way, but it sounds like a giant striding over an open field, the upward pitch movement of the sequence creating an illusion of forward momentum and quickening speed. Several more bars are spent on the previous instrumental material, with a development section from quiet to loud, peaceful to aggressive, magically returning to the “stride” motif, calming down again, with repetition ever a component, followed by a return to the dramatic surreal vocal section and then the stride motif once again, with a brief rock representation of pointillism and a return to the main instrumental theme with synthesizer. The song then dramatically (and tidily) ends with a Gentle Giant flavored classical-style authentic cadence. All-in-all a pretty wow experience — only surpassed in inaugural albums by King Crimson’s “21st Century Schizoid Man.”

This then, strangely and appropriately enough, is followed by the Beatlesque “Isn’t Quiet and Cold” with Ray Shulman providing a perfect alternation of pizzicato and bowed violin. There are no strange detours here — it’s all very straightforward and beautiful — with Minnear’s hard-mallet xylophone solo being particularly engaging. This ends side one.

Side two opens up with a similar tone to the last track on side one, again sounding Beatlesque. But GG is more adventurous here — after stating the song in full (two and a half minutes), they tiptoe into development territory taking a bass countermelody from earlier and briefly exposing it with a hint of the sinister, then a quieting down, revisiting it with new material — a bridge in a sense — and showing off Derek Shulman’s signature glissando vocal-style and Gary Green’s outspoken guitar commentary. The shimmering of a gong takes us to a contrasting section of mostly reverberated percussion and some piano quoting Liszt — one of only two classical music quotes in all of GG’s studio albums (the other being a retrograde quote of Stravinsky in their last album), which then eventually gives away to the recap of the original song. This is by a wide margin the longest studio track Giant ever recorded — for a prog-rock group it’s remarkable to note that their longest song is well under ten minutes — this in the prog-rock decade where single sides and even albums were sometimes a single piece.

The album ends relatively weakly with the partly hard rock “Why Not” including a pleasant, contrasting Kerry Minnear middle section with Phil Shuman on tenor recorder and then some solid electric guitar work, and an unremarkable though pleasant-enough treatment of “God Save the Queen.” Album is produced by Tony Visconti.

And yet despite weaknesses this is an album full of notable melodic and transitory material that promises much for future albums — with those albums eventually meeting and exceeding that promise. This, in itself, makes this first album more than a collection of varied songs, but a historical artifact providing insight into the later works.

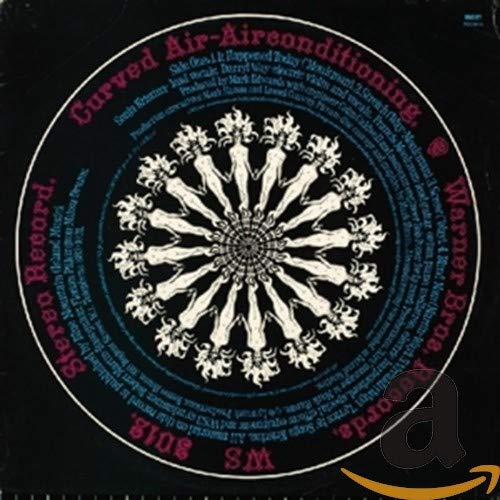

Curved Air: Air Conditioning

Recorded in July of 1970 and released in November of 1970, Curved Air’s debut album, Air Conditioning, did very well in the UK (#8.) Their name is based on the title of Terry Riley’s composition, “A Rainbow in Curved Air.” The band has some superficial similarities to the American Jefferson Airplane partly due to Sonia Kristina’s dark, evocative voice and partly due to hard rock, folk-rock and psychedelic rock components in the music. Add to this Darryl Way’s violin, Francis Monkman’s guitar work and keyboards and the skilled way each song is realized and the result is a distinct, progressive, and somewhat symphonic sound. The best known song is “It Happened One Day”, which received some FM radio airplay and was included in an 1971 Warner Bros Loss Leader album. It opens side one which includes the wispy “Screw”, the Donovan-inspired “Blind Man” and the Vivaldi-inspired “Vivaldi” with relentless multi-tracked electric violin followed by a Vivaldi-like cadenza that evolves into a multi-part, feedback-based cadenza-like section, then a free-form Hendrix-like section eventually reprising the original theme with heightened intensity and closing with a brief coda.

The dramatic “Hide and Seek” decisively starts the second side, is every bit as impressive anything on side one, and is followed by the upbeat and syncopated Propositions. “Situations” in A-B-A form includes a notable (also a-b-a structured) middle section that starts with an airy, floating vocal passage, followed by a guitar dominated section with a return to the “a” section and then, of course, returning to the main “A” section. The album ends with a hyped-up recap of “Vivaldi” aptly named “Vivaldi with Cannons.”

George Harrison: All Things Must Pass

With all the enticing albums on the shelves at the big retail record stores (the Warehouse in Southern California, particularly), Christmas time of 1970 was particularly memorable. There was Jesus Christ Superstar and so many other tempting musical wonders on display with George Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, released on November 27th, and All Things Must Pass looked the most tempting of all — a triple record set that promised ample listening material. Immediately upon release, the album received notable air play on the FM album-oriented stations and there was no hesitation for me to purchase it after Christmas with my available extra money I had received on Christmas Day.

The album starts off relaxed, with the Harrison/Dylan collaboration, “I’d Have You Anytime” setting the mood with its tranquil first verse — a mood that I associate with the album to this day. This is not loud in-your-face hard rock, but an acquired taste: subtle and reflective full of special moments like the Clapton guitar solo on the first track. It’s not accurate to say every song is a gem, but the many strong songs function to bring the rest of the album into balance, making it a delight to either sit down and listen studiously to or put on as background music. Now, when I reference the “album” I mean the first two LPs. The third, I have always viewed as a bonus album — a pastiche of jam numbers that after initial listening when I first bought the album set, received only occasional playing, and mostly when I engaged in some other activity, like homework or reading. Listening again to this third LP this week, I find it still does not pull me in any notable way, but those first two LPs are as magical as when I first listened to the album during the last days of Christmas vacation 1970.

Badfinger: No Dice

As mentioned, I had extra cash post-Christmas in 1970/1971 and previously impressed by Badfinger’s music in the movie Magic Christian and their rendition of Paul McCartney’s “Come and Get it” as well as a recent review I had read that compared them to the Beatles, I bought “No Dice.” I found it a little Beatlesque — but not in the Abbey Road or White Album sense, but in the “Old Brown Shoe”, “Don’t Let Me Down”, and “Ballad of John and Yoko” sense — only not as good. Yet it was still a pretty good album, at least to listen to half-a-dozen or so times and put it away for almost 50 years. Listening to it again, the best tracks, like “No Matter What”, “Without You”, “We’re For the Dark,” make the album a worthwhile listen even if a few of the weaker tracks approach the dull side.

Derek and the Dominos: Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs

I immediately fell in love with “Layla” the first time I heard it on FM radio, hearing it as two songs, which is what it was, spliced together. Derek and the Dominos were formed by guitarist Eric Clapton and keyboardist Bobby Whitlock in the summer of 1970 to play mostly music created by them earlier that year. Added to the band were Jim Gordon on drums (first choice was Jim Keltner who was unavailable) and Carl Radle on bass with appearances from Duane Allman and Dave Mason. The album, Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs, a 2LP set, was released on November 9, 1970 and received mixed reviews, some very negative. Outside of “Layla” and the catchy part of “Tell the Truth”, the rest of the album fails to spark any strong interest for me despite several tries. The musicianship is strong but most of the songs are just run of the mill, mostly anchored in I IV and V chords with mostly ordinary rhythms and melodies and limited metric and harmonic contrasts. Even the inclusion of Hendrix’s “Little Wing” doesn’t work for me as, really, the original is so much more full of life and energy. Nonetheless the album is worth having just for “Layla.”

Grateful Dead: American Beauty

Grateful Dead released their fifth studio album, and second of 1970, with American Beauty, an appealing, heartfelt work that many fans rank as either their best or at least their second best studio album to the earlier Workingman’s Dead. The Dead incorporate the bluegrass musical ethos better than any other rock group. Though I generally shy away from most country music and most country-rock, I am strongly attracted to bluegrass, and love listening to live bluegrass bands, particular in their home settings in states like Kentucky or West Virginia. So even though this Grateful Dead album is far from authentic bluegrass, and may lack the passion and ardor of the finest bluegrass music, it captures and incorporates enough of that bluegrass spirit to enrich and elevate the album. “Candyman”, the final track of the first side, is a great example of how the group starts with blues-like lyrics and a pretty traditional country musical framework and by using the right chord changes, some yearning steel-guitar work, leisurely electric organ, and properly placed supporting choir-like vocals makes the song a special experience.

The second side opens up with “Ripple”, a relaxing, tonally stable, country-style, gospel-tinged ballad with its reassuring words of wisdom and then continues with a couple more Robert Hunter compositions reportedly written that same afternoon: the gentle gospel-influenced “Brokedown Palace” and the more upbeat, and more carnally-grounded “Til the Morning Comes.” The album ends with the classic “Truckin”, an anthem of attitude for the beginning of the seventies:

“Truckin’, got my chips cashed in

Keep truckin’, like the do-dah man

Together, more or less in line

Just keep truckin’ on.

“Once told me, “You’ve got to play your hand”

Sometimes the cards ain’t worth a dime

If you don’t lay ’em down.”

Spirit: 12 Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus

Released on Nov 27, 1970, Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus, Spirit’s fourth studio album, is another album that didn’t do particularly well when released, charting lower than their three previous efforts, but over time ended up being their best selling album going gold in 1976. The album’s first side is particularly strong with the undisputed gem being Randy California’s “Nature’s Way” which didn’t get very far up on the Billboard singles chart, but became a standard on FM radio, particularly as the environmental movement picked up steam. The second side continues with the same general energy starting with a strong instrumental by the keyboardist John Locke and a couple of quality songs by vocalist Jay Ferguson with some impressive guitar work by California on “Street Worm”, and then closing with three endearingly distinct Randy California tunes.

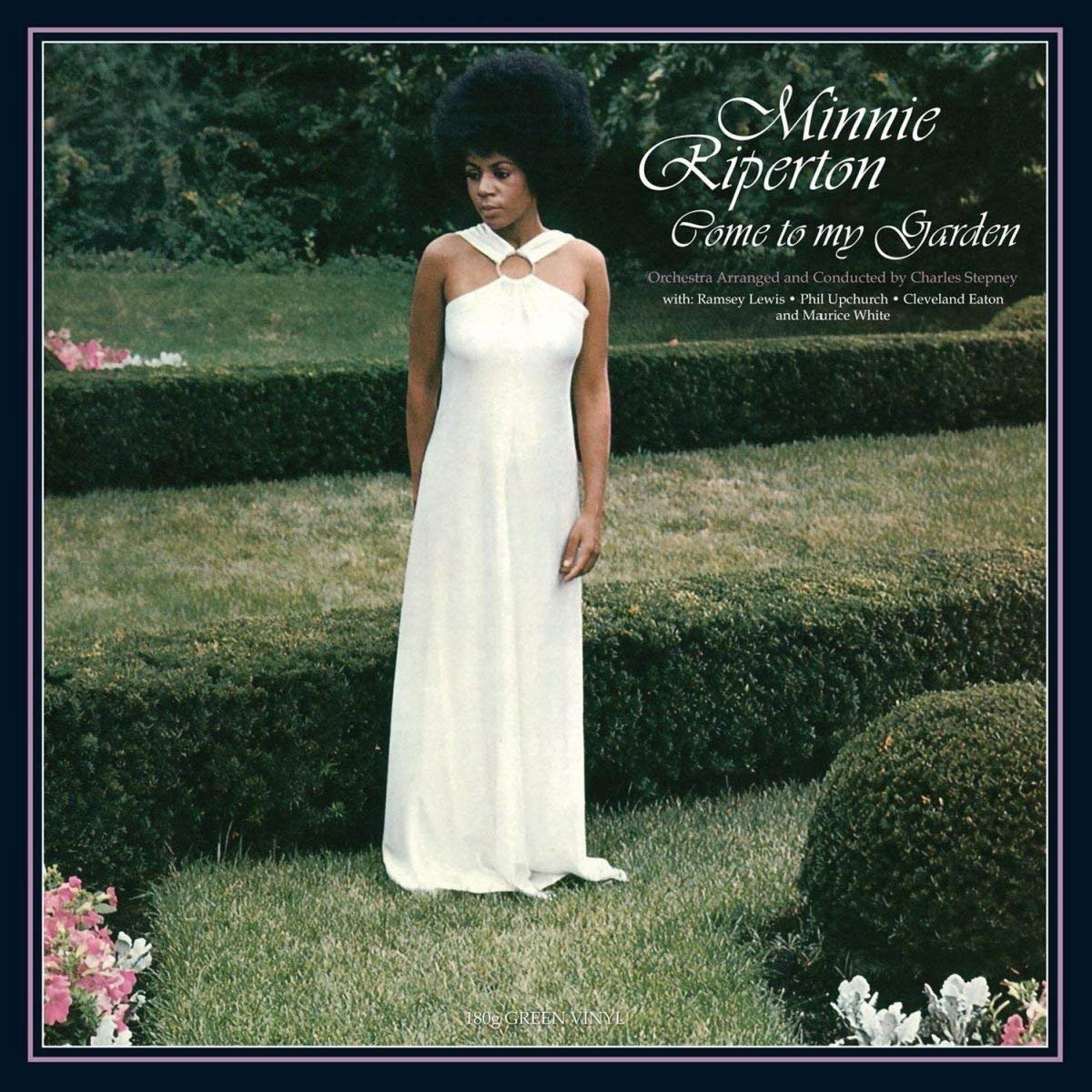

Minnie Ripperton: Come into My Garden

Released in November 1970, about a year after it was recorded, Minnie Ripperton’s debut solo album, Come Into My Garden, is a fine album that received little attention until her more commercially successful album was released in 1974. Minnie originally studied opera singing but eventually pursued her greater love for pop and soul music and in 1967 became a vocalist in The Rotary Connection.

In Come Into My Garden she displays her unusual upper-range vocal skills, but more impressive is her beautiful diction, phrasing and sublimely smooth vocal delivery. Her future husband (actual husband by August 1970) co-wrote some of the songs with additional material and arranging by Charles Stepney, keyboardist and songwriter of the Rotary Connection. Though “Les Fleur”, the opening track, is the most distinct and memorable song in the album, the excellent arrangements and superb execution elevate the rest of the album to delicate, graceful and sensuous musical experience.

At some point one has to wrap up a blog post even when there are many more albums to cover. There is the excellent Stephen Stills album, for example, as well as some lesser, but still notable albums like Kraftwerk’s unfettered self-titled debut and Isaac Hayes’ well-arranged To Be Continued. There is Family’s part live and part studio Anyway, Syd Barrett’s enjoyable second studio album, Barrett, Pentangle’s shimmering, though dark in subject matter, Cruel Sister, Steve Miller’s solid fifth album, titled Number 5, Tim Buckley’s brilliant, free-jazz influenced Starsailor, Laura Nyro’s excellent Christmas and the Beads of Sweat and several “Best of” albums that came out in November 1970. Certainly many of the releases, particular the “Best Of” LPs were timed to come out to be available for the holiday gift-giving season. That said, I don’t think one will find another month quite like November of 1970. At least not for classic rock.