Fifty Year Friday: November 1969 including David Bowie and Almendra

Somos seres humanos

Sin saber lo que es hoy un ser humano

(We are human beings, without knowing today what a human being is.)

— Almendra

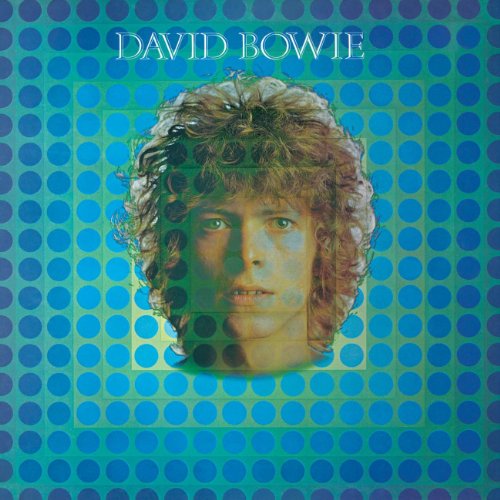

On Nov 14, 1969, Philips released David Bowie’s second album in the UK, originally titled “David Bowie.” Mercury released the album in the US as “Man of Words/Man of Music” which was re-released by RCA in 1972 as “Space Oddity” after the success of the Ziggy Stardust album. Whereas Bowie’s very first album sounds like he is intentionally imitating Anthony Newley and includes mostly songs of limited musical and lyrical depth, this second album raises the level of artistry considerably, bringing together a few easily accessible songs with several more carefully crafted, more reflective numbers. Perhaps Bowie’s break up with his deeply-loved girlfriend, Hermione Farthingale contributed toward a decided shift to a more personal artistry. Bowie thought of her as a soulmate and suffered deeply from the end of their relationship — two songs on this album are clearly about her: “An Occasional Dream” and “Letter to Hermione” — both providing an insight into the impact of the loss.

With the exception of the second track, “Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed”, a clear homage to Bob Dylan, Bowie is mostly his own artist on this album, produced mainly by Tony Visconti, who also plays bass. One track, the single “Space Oddity”, which Bowie wrote after seeing Kubrick’s “2001, A Space Oddity”, was produced by Gus Dudgeon and climbed up to the number 5 position on UK charts, though in the U.S. it did not fare any better than the 124th spot. The general US AM listener would not be exposed to it until 1973 when it reached the 5th position and then again, in 1975 when it made the #1 spot and seemed to be played unceasingly.

The album includes Rick Wakeman on mellotron and harpsichord and Gus Dudgeon on cello. It will be another year before Bowie works with Mick Ronson and Mick Woodmansey and another year after that until Trevor Bolder is added on bass. Though there are many better albums to follow, this may be the most personal and the one closest to reflecting the native-state David Bowie as opposed to Bowie the mastery of multiple external personnas and styles.

In November of 1969, Colosseum release their second album, Valentyne Suite, which did fairly well in the UK, reaching number 15 on the UK album charts. The highlight of the album is Dave Greenslade’s contributions, both as a performer on keyboards and as a composer on the first two sections of the three movement Valentyne Suite. Interestingly the original version of the suite was included in the 1969 US release of Colosseum’s previous album “Those Who Are About to Die Salute You”, which is a combination of the first and second UK albums. For the UK version of the second album, the original third part of the suite, “Theme Three, Beware the Ides of March”, co-written by Greenslade, Dick Heckstall-Smith, Jon Hiseman and Tony Reeves is replaced by “The Grass is Always Greener” co-written by Heckstall-Smith and Hiseman, since “Beware the Ides of March” had previously appeared on the first album. The suite works in either configuration and provides a strong ending to both the UK version of the second album and the US version of “Those Who Are About to Die Salute You, which is a mix of tracks from both the first and second UK albums.

Other November 1969 albums include Steve Miller’s Your Saving Grace and Jefferson Airplane’s Volunteers, both albums including Nicky Hopkins on keyboards. Volunteers is the more significant album historically and musically, containing both strong language and strong political content.

Steppenwolf’s Monster, also released in November 1969, starts with a similarly strong political message. recounting how “Like good Christians some would burn the witches;

later some got slaves to gather riches.” and “While we bullied, stole and bought a homeland, we began the slaughter of the red man”, and warning of the inevitable transformation into a monstrous beast with cities turned into jungles, strangling corruption, and the costly Vietnam war.

Moody Blues released To Our Children’s Children’s Children on November 21, 1969 with the first track “Higher and Higher” and the general thematic direction of the album inspired by the Moon Landing. The album continues to distill the Moody Blues identifiable sound with tracks melting into each other. The album reached number #2 in the UK and #14 in the US.

Amidst a number of other November 1969 albums, many of them debut studio albums like those by the Allman Brothers and Mott the Hoople, Rod Stewart releases his first album, around 32 minutes of music including Ronnie Wood on guitar and Keith Emerson on organ on “I Wouldn’t Ever Change a Thing”

Humble Pie’s second album, the appropriately named Town and Country, released November 1969, provides an attractive balance of acoustic and electric guitar work with some Wurlitzer piano. The album contains a good measure of country-rock, two strong Peter Frampton songs, and Steve Marriot’s particularly evocative, mood-setting, “Silver Tongue.”

Kevin Ayers released his debut album, “Joy of a Toy”, in November of 1969 — a slightly tongue in cheek, intentionally laid back and understated set of songs that look forward to indie rock of the 1980s as much as an distillation of Soft Machine, sixties rock, show tunes, pop and early progressive rock. Even though the lyrics range in quality, the nature of the music and Ayers delivery always make the words work well with the music. The opening instrumental sets the appropriate mood, followed by the wry “Town Feeling” with effective oboe and then “Clarietta Rag” which sounds a bit too much like “For the Benefit of Mr. Kite”; a variety of songs follow, some having that identifiable “Canterbury” sound, some like “Religious Experience” which seems more spur of the moment composition and performance, and includes an appearance from Syd Barrett. Perhaps the best tune is “Lady Rachel” with a mysterious oboe introduction nicely setting the mood as well as the the colorful orchestration and the judicious use of a chromatically-raised augmented chord in the chorus. Musicians include Robert Wyatt, Michael Ratledge and Hugh Hopper from Soft Machine as well as David Bedford on piano and mellotron and Paul Buckmaster on cello. All in all an under-the-radar album (at that time and now), that had better material and more an influence on music than generally given credit for.

Argentina bands, as with bands from other Latin American countries, mostly were imitative or cover bands for most of the sixties. This “Nueva Ola” style, represented by local bands (having English names), though popular enough and providing live music, couldn’t compete in terms of record sales with new music from U.S. and Britain, and eventually the “Rock en Español” musical movement produced bands like Los Gatos and Almendra.

Led by songwriter, guitarist and vocalist, Luis Alberto Spinetta, Almendra released their first album, the self-titled Almendra, on November 29, 1969. How much this influenced future progressive rock bands in South America, Spain and Italy is not clear, but the album, like Spanish and Italian music to follow, incorporated folk music together with jazz, pop and rock elements.

The album opens with their earlier released, and successful single (in Argentina), “Muchacha (ojos de papel)”, a modern art song with beautiful melody and lyrics over Spinetta’s acoustic guitar. Another highlight on the album is Spinetta’s “Figuración” which alternates between a gorgeous folk-like melody and a rock section anticipating future Italian prog-rock groups like PFM. This is followed by the upbeat and partly Beatles-like “Ana no Duerme.”

Side two opens up with reflective, acoustic folk-like “Fermin”, followed by the equally graceful “Plegaria para un niño dormido” and the multi-thematic “A estos hombres tristes.” Bass guitarist contributes the jazzy, almost Brazilian-like “Que el viento borró tus manos.” The poignant and elegant “Laura Va”, with harps, strings and woodwinds provides a graceful and satisfying end to one of the best albums of 1969.

Woodstock: Aug 16-18

Woodstock: Aug 16-18

Recorded on May 17, 1968, and released in August of 1968, McCoy’s Tyner sixth albums feature the trio of Tyner, Herbie Lewis on bass and Freddie Waits on drums with the addition of Bobby Hutcherson on vibes for the first side of the two lengthier Tyner compositions and the the first two tracks on side two, Tyner’s “May Street” and Richard Rodger’s “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” from the 1939 Musical, “Too Many Girls.”

Recorded on May 17, 1968, and released in August of 1968, McCoy’s Tyner sixth albums feature the trio of Tyner, Herbie Lewis on bass and Freddie Waits on drums with the addition of Bobby Hutcherson on vibes for the first side of the two lengthier Tyner compositions and the the first two tracks on side two, Tyner’s “May Street” and Richard Rodger’s “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” from the 1939 Musical, “Too Many Girls.”

\

\