Fifty Year Friday: November, 1971

Looking back fifty years, one can identify a number of months in the early 1970s, particularly those approaching the end of year, whose bounty of riches border on the spectacular. Such is the case with November 1971, which I could easily argue is the very best month of releases in the entire history of the Long Playing record — and going beyond that, extending also into the digital (CD and streaming) age.

Besides highlighting some of the more outstanding releases of November 1971, I also have included a few albums I had missed mentioning earlier — albums released in 1971, but before November. That certainly gives us a lot to cover, but whether fortunately or unfortunately for you, the reader, my time to do blog writing is extremely limited — and this month, I have almost no bandwidth. I am going to be challenged to just list my favorite albums, let alone say anything of substance. However, as regular readers can attest, I rarely say anything substantial in this column anyway (thankfully the music stands on its own) and I do my best to say a few words of no special consequence in my limited time. I certainly can’t, wouldn’t and have no reason to fault any reader that prefers to just quickly glance at what albums are mentioned, which by itself justifies my effort and is as much as I expect and actually have any reason to expect. That said, I am going to see how much I can tackle before the last friday of the month arrives, and as I always have done, post whatever I have, whether readable or not.

It’s also important to note the increasing prevalence of synthesizers in so many albums of this time period. Ever since hearing Switched on Bach around 1969, I developed an undeniable affection for the thrilling portamento and the more blatantly artificial wave forms produced by keyboard synthesizers. In November of 1971, we get several classic albums that place the synthesizer in a very prominent role.

Yes: Fragile

Yes releases their fourth (and finest up to that date) studio album on November 26, 1971. Rick Wakeman has been added to replace Tony Kaye, further raising the potential of the group — potential that was immediately realized starting with this fourth album, Fragile, a classic from the day it was available in record stores — and classic, not just in the sense of being of highest merit and quality, but in terms of stylistic characteristics such as direct, concise, clearly defined, and finely balanced components as well as an elegant use of contrast — both in mood and musical dynamics. The music avoids excesses and, with a couple of minor exceptions, is economical, avoiding the kind of excessive repetition so prevalent in most rock music.

Yes went into the studio with four finished compositions which make up most of the album. All of these four tracks received some FM airplay, and a slimmed down version of “Roundabout” received significant AM airplay peaking at 13. For the remaining portion of the album each band member contributed their own solo works, with Wakeman’s condensation of the Brahms quasi-scherzo from the 4th symphony, Anderson’s “We Have Heaven” and Bruford’s “Five Per Cent for Nothing” all being distinctly original. With the exception of Howe’s “Mood for a Day” and Squire’s “The Fish (Schindleria Praematurus)”, both still excellent and contribute to the stunning impact of the album, but which are slightly overextended through repetition of material, this album approaches perfection, achieving a level of musical distinction equal to the very best rock albums of all time.

Emerson, Lake and Palmer: Pictures at an Exhibition

Recorded in March of 1971 and released in November of 1971, this exuberantly energetic live album captures Emerson, Lake and Palmer’s concert rendition of Modest Mussorgsky’s classic piano suite, Pictures at an Exhibition. Already in love with ELP’s first two albums, this would have been an album I would have purchased on sight. However, it was my next door neighbor that sighted it first, bought it immediately, and brought it over for me to listen to and record on my reel to reel for future listening. At that point, cash-constrained as most sixteen-year olds, I was content to listen on that 3 3/4 IPS (inches per second) copy of the album over and over again until college when I finally bought my own LP copy of it.

Prior to this recording, most people knew of Mussorgsky’s great work from Maurice Ravel’s orchestral version. Ravel is one of the great composers of the first part of the twentieth century, and very skilled at orchestration with a number of his own compositions, originally written for piano, then very effectively scored for an orchestra. He had worked with Stravinsky on a performance version of Mussorgsky’s unfinished opera, Khovanshchina, and thus very well prepared in 1922 to tackle Pictures. The result was an excellent work, but was clearly Ravel’s own vision and interpretation — the original, which deftly represents both the viewer of the gallery and his mood and perceptions of the objects on display, is quite different from Ravel’s interpretation, with the original piano composition having a darker and more inward perspective. Ravel is focused on creating a grand work with its own identity, bringing to the table his own compositional and cultural mindsets and not particularly beholden to the mood and intent of the original. That doesn’t mean that this final orchestrated version is any less worthy of being enjoyed because it isn’t particularly faithful to the spirit or personality and attitude of the original — it just means it should be listened to and enjoyed on its own terms. The same pretty much applies to ELP’s version, which not only “orchestrates” the original piano work with modern rock trio (keyboards, bass, drums) but also adds vocals and new material.

Of course, the piece starts off with the promenade theme, played very simply by Emerson but with the grandeur that a real organ, the organ used at Newcastle City Hall (the venue for the live recording), can provide. The first picture follows, “Gnome”, with Palmer’s staccato and perfectly punctuated percussion dancing with Lake’s bass, providing the appropriate dramatic setting for the eventual entrance of Emerson’s moog synthesizer — making clear this is not Ravel’s concert hall Pictures. This, then, is the final catalyst to fully engage the listener into the magic and ferocity of this post-Ravel, prog-rock version of Pictures. The album ends with ELP’s take on Kim Fowleys’ take on Tchaikovsky’s “March” from his Nutcracker Ballet.

It’s worth noting that ELP’s Pictures at an Exhibition was at one point considered more appropriate as a Nonesuch Records label release due to its classical origins. It might have also been part of a 2 LP set with Trilogy (ELP’s subsequent album), except that public demand, particularly after the concert recording was played on WNEW-FM (New York), convinced the Atlantic execs to release it sooner, and as its own album.

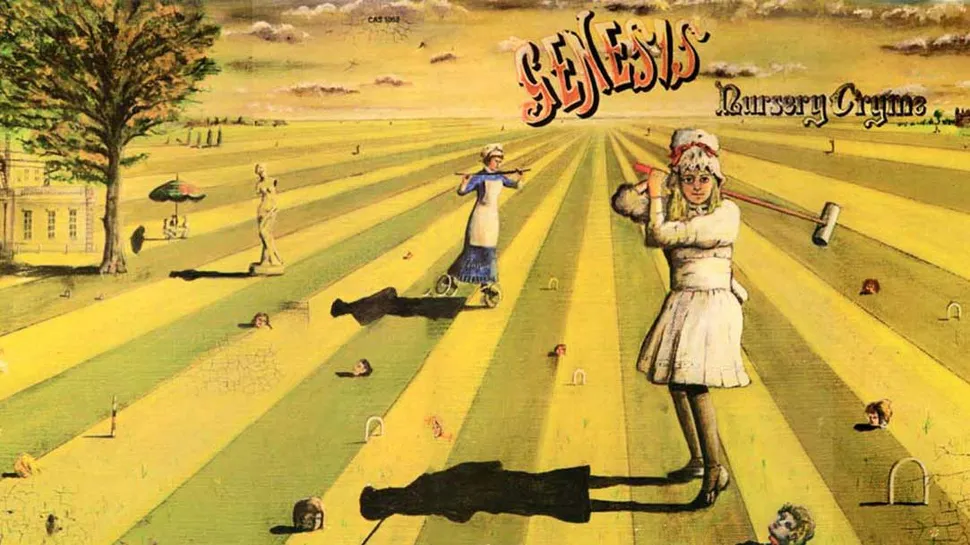

Genesis: Nursery Cryme

Released November 12, 1971, this already highly creative and musically skilled group adds world-class drummer, Phil Collins. Though Nursery Cryme is not at the level of sound quality as Yes’s Fragile or quite as impressive in terms of focused musical content, this is a nuanced, highly crafted album that starts off incredibly strong with “Musical Box” and includes Genesis’s first masterwork, “The Attack of the Giant Hogweed.”

Traffic: The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys

This classic fifth studio album was a staple of FM AOR (album-oriented radio) stations, with “The Low Spark of High Heeled Boys” getting most of the airplay, but the rest of the album getting some time also. In fact, I am pretty sure this was the second rock album I heard played in full on FM radio (the first being Webber and Rice’s Jesus Christ Superstar, which was played in its entirety in very late October or very early November of 1970.)

Led Zeppelin: Led Zeppelin IV

On November 8, 1971, Atlantic Records releases Led Zeppelin’s masterpiece, the unnamed, untitled fourth album. Atlantic internally catalogued it as Four Symbols and The Fourth Album. We used to call it “Zofo” from the first of those four symbols on the LP label. People smarter than us, or people from England who were more used to lines crossing through lower case “s”s than those of us in Orange County, California, would just as incorrectly call it “Zoso” since the designer of the symbols, guitarist Jimmy Page had not intended for these four symbols to represent anything rather than the four band members of Led Zeppelin.

Now I admit, I would rather listen to the guitar craft of Jimi Hendrix, or the two guitarists I mention later in this blog post, John McLaughlin and George Benson, or a number of other guitarists such as Django Reinhardt, Eddie Lang, Wes Montgomery, Jim Hall, Grant Green, Tal Farlow, Gary Green, Steve Howe, Robert Fripp, Steve Hackett, Andrés Segovia — as well as a number of others — however, I still enjoy every moment of Jimmy Page captured on this album, a unquestionably skilled and creative guitarist at the world class level.

In fact, I pretty much enjoy every moment on this album — one of those musical treasure chests of the early 1970s. It may not generally be labelled as progressive rock, but it really is, from the focused abstraction of rock and roll in “Black Dog” to the refined distillation of rock and roll in “Rock and Roll”, to the epic “The Battle of Evermore” with its gorgeous acoustic guitar, to the bouncy, again abstract, “Misty Mountain Hop” and the frenzied and contrastingly uplifting “Four Sticks”, to the best work of the album, “Stairway to Heaven”, possibly consciously or unconsciously influenced by Spirit’s “Taurus” (Led Zeppelin opened for Spirit for Spirit’s 1968 U.S. tour) but nonetheless a definite improvement over the alleged original. Though I may be a bit more advanced in my musical tastes today, I vividly remember listening to this album on headphones almost fifty years ago, the album borrowed from my next-door neighbor who purchased it in late November or December of 1971, and being totally swept away by the impact of the entire album.

Sly and the Family Stone: There’s a Riot Going On

Released on the first of November, 1971, created by Sly Stone during the depths of his stratospheric-recreational drug abuse, this is a masterpiece not only to be taken very seriously musically and artistically but even more seriously historically.

The album starts of with the incredible “Luv N’ Haight”, a psychedelicized, celebratory blues-based number, underpinned by lyrics that could either be interpreted as also celebratory (“Feel so good inside myself, don’t want to move”) or subtly dark (“As I grow up, I’m growing down and when I’m lost, I know I will be found.”) The lyrics for the second track provide the same type of ambiguity (“Just like a baby everything is new” and “Just like a baby sometimes I cry. Just like a baby I can feel it when you lie to me.’), and though open to a wide range of interpretation, appear to be referring to rebirth or re-awakening, though not clear if from some spiritual rebirth or transformation, or from drugs or trauma. The third track seemingly unsubstantial with simple lyrics that still get to the heart of songwriting (“My weapon is my pen and the frame of mind I’m in) is one of the most sampled songs ever.

The fourth track, “Family Affair”, one of the highlights of the album, was played substantially on AM radio starting in early November 1971, and went over my head both musically and lyrically, excused to some degree by only hearing it on the shoddy speakers of our school bus that took us over to our high school. In terms of lyrics, it is open to interpretation, but I think the interpretation is clear when one embraces the two apparent co-existing meanings: commentary on nature versus nurture (the disadvantages of being in a disadvantaged family unit) and family bonds. Underscoring these meanings is the understated arrangement (I believe Freddie Stone on guitar, Billy Preston on keyboards, and bass and drums) and assignment of vocals to just Sly and his sister Rose, particularly inviting us to connect “One child grows up to be somebody that just loves to learn and another child grows up to be somebody you’d just love to burn” to Rose and Sly, respectively. This is followed by the bleak “Africa Talks to You” (“Timber, all fall down”) with its eventual complex instrumental interplay, which contrasts sharply with the simpler music of the previous track. The first side ends with an absent track (or a track of zero length, if you prefer), “There’s a Riot Goin’ On” — a very clever commentary which Sly intended to simply indicate that since he didn’t like riots, there was no corresponding song. The second side continues with more excellent music, including the infectious “(You Caught Me) Smilin’ — once again apparently intentionally ambiguous as to whether it is statement against or for drug usage: “You caught me smilin’ again, hangin’ loose, ’cause you ain’t used to seeing me turnin’ on, ha ha” and “I ain’t down. I’ll be around to carry on!” Is this ironic and sarcastic or in praise of the release that drugs provide?

Besides admiring the artistic merit of the album, it’s worth considering its historical impact. Though there are plenty examples of funky music and elements of funk before Riot (a common pet name for this album), this really is the first modern funk album, influencing many artists of all backgrounds and musical leanings. It also is substantially the first hip hop album — not in terms of musical style, of course, but in terms of narrative and borderline-obsessive personal reflection. And, I will boldly, if not controversially venture, that if we remove this album from the historical river, that the currents of disco would have been perceivably altered — maybe for the worse, if that’s conceivably possible. It worth noting, that many critics did not get this album at all when it came out, including our local Southern California L.A. Times music critic who generally was befuddled by, or more often shied away from (handing the review to another staff writer), any music with any level of complexity. Now fortunately, just about all music critics are in unison when acknowledging both the artistic and historical merit of this fine album.

Osibisa: Osibisa

With the increasing interest in World music, particularly that from the Caribbean and West Africa, conditions were receptive for a jazz-influenced, musically compelling, Afro-beat group of four Ghanaian-English musicians and three Caribbean musicians. Osibisa’s first album, released in the first half of 1971, made its entry into the Billboard 200 the first week of July, 1971 at position 105, climbing up to position 55 by mid-August. The rhythm section is incredible (remember their inclusion on Uriah Heep’s title track of Look At Yourself) with the dedicated drummer supplemented by other members of the group as appropriate. Instruments include assorted percussion, flute, saxophones, trumpet, flugelhorn, organ, piano, guitar, bass guitar and some vocals. Album is both technically impressive, and musically vibrant, filling in the checkboxes for world music aficionados and progheads alike.

Osibisa: Woyaya

The second album, released in late 1971, has a similar Roger Dean album cover to the first, and the band members are the same (with the exception of an appearance of the “Osibisa choir” which provides an additional uplifting, spiritual to the third track, Roland Kirk’s “Spirits Up Above”), yet the quality is noticeably different — better engineering, less spontaneous but now exquisitely polished, and leaning more towards American jazz and even English progressive and psychedelic rock with less of a West African and Caribbean feel — even containing some American funk (“Move On”.) Though this album fell short of the previous album’s climb up the Billboard charts (only 66 compared to 55) it is even better than the first, perhaps with a greater appeal to a broad audience, particularly with the anthem, title-track, “Woyaya” being covered by Art Garfunkel and The 5th Dimensions and used as the theme for a Ghanaian television show from 1972 to 1981.

Assagai: Assagai

Though less musically stylistically diverse than Osibisa, Assagai’s first album is a enjoyable blend of African folk, African rock, and African jazz elements. The group consists of band members on cornet, alto sax, tenor sax, and drummer — all from South Africa — and an electric guitarist and an bass guitarist from Nigeria, with some additional piano possibly from the alto sax player, Dudu Pukwana. Album is mostly original material by the guitarist, Fred Coker, with one composition by Dudu Pukwana, one collaboration between Coker and Jade Warrior guitarist, Tony Duhig, as a well as a cover of Jade Warrior’s “Telephone Girl” (from their first album) and Paul McCartney’s “Hey Jude.” Of all the various covers of Hey Jude I know of, this is one of the best, relatively brief at under 4 minutes, and infused with a rich tapestry of Afro-beat seasonings.

Jade Warrior: Jade Warrior

(One of the albums I previously missed covering in Fifty Year Friday.) In 1970, Vertigo signed Jade Warrior primarily due to Mother Mistro, the production company for both Assagai and Jade Warrior, insisting that Vertigo couldn’t sign Assagai, a group coveted by Vertigo for their commercial potential (based on Osibisa relative success) without also signing Jade Warrior. Vertigo, though, had made up their collective mind that Jade Warrior had very little commercial potential and so didn’t put in any real effort promoting Jade Warrior’s first album, Jade Warrior, released sometime in the first part of 1971. Interestingly, Assagai would release a total of two albums, both on Vertigo, while Jade Warrior would release well over a dozen with the first three on Vertigo, and the next four on Island Records.

Even if this first album was not particularly commercially appealing, it was musically so, opening up with the beautiful “Traveller” with its simple acoustic beginning, its majestic middle section, and its quiet ending followed by the more aggressive, mostly pentatonic “A Prenormal Day at Brighton” providing a good representation at Jade Warrior’s balancing act between hard progressive rock (“warrior” portion of the group’s name) and soft worldly folk rock (“jade”), sometimes with emphasis on acoustic guitar and flute with some additional, non-traditional percussion and sometimes more in a rock idiom with the electric guitar in the forefront. Overall a fine eclectic album that still sounds great today.

Jade Warrior: Released

With their second album, Jade Warrior shifts away from a world music vibe to focus more on hard rock, jazz rock and progressive rock elements, adding two new members, Dave Conners (sax, flute) and Allan Price (drums) to the pre-existing trio.

Ash Ra Tempel: Ash Ra Tempel

Another album I missed mentioning, released around June of 1971, is the classic first album of Ash Ra Tempel, one of the finest German space rock albums, a style often referred to as Kosmische Musik (cosmic music.) We have a single composition on each side, improvisations similar to what one could expect during a live performance. The first side is adventurous, extroverted and like a peril-filled voyage through outer space, starting gently and then encountering the more unpredictable moments of cosmic exploration. The second side is calmer, introverted and reflective, like a journey through spiritual innerspace. Overall, far above one of the best musical adventures of space rock, each of these two tracks compelling and creating an unfolding, meaningful soundscape.

Strawbs: From the Witchwood

And yet another album I missed earlier, the Strawb’s Witchwood starts off pretty much as folk music, by the third track is it full-throttle prog rock. This is Rick Wakeman’s last album for the Strawbs, and his keyboards raises the album up the scale of musical excellence including an effective organ intro for “The Hangman and the Papist.” Overall there are some similarities with Genesis’s Nursery Cryme and Foxtrot, both of which were recorded after From the Witchwood was released.

Le Orme: Collage

Le Orme’s first album, recorded in 1968 and released in 1969 was effectively an early prog rock album, with an album title of Ad Gloriam, an opening track named “Introduzione”, a closing track titled “Conclusione” and many of the lyrical and the Italian rock equivalent of the bel canto elements that would become identifiers of the Italian Prog rock style. With their second album, Collage, released sometime in 1971, they shift to full prog mode, reducing the group to a ELP-like trio, quoting the classics (or at least Scarlatti’s K. 380 sonata, a piece I heard over and over from piano student performances during my university years), and exploring the more aggressive and bombastic aspects of early Italian prog but not abandoning the lyrical or expressive components.

Man: Do You Like It Here Now, Are You Settling In?

Man released their fourth and strongest album so far on November 1971. Though a bit uneven, the musicianship is consistently strong with some ear-catching instrumental interplay such as that on “All Good Clean Fun” and “Many are Called, But Few Get Up” that further increases the impact of the album.

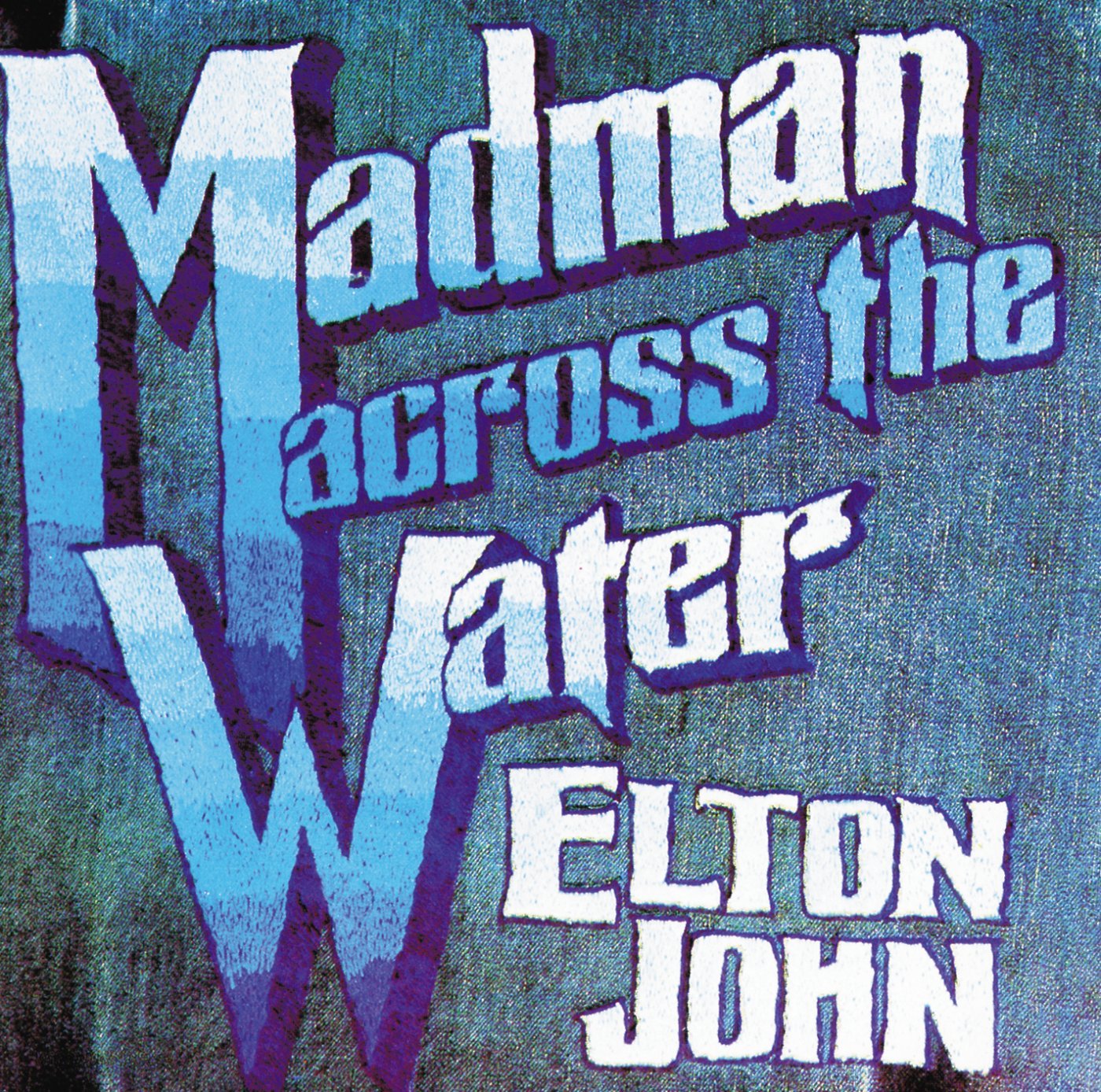

Elton John: Madman Across the Water

Another fourth studio album released, this time by an increasingly popular Elton John. Though Madman didn’t climb quite as high on the Billboard charts as Tumbleweed Connection (number 8 vs number 5) and the airplay provided “Tiny Dancer” couldn’t match “Your Song”, the prevalence of Elton John albums in personal collections was steadily growing. Paul Buckmasters arrangements are applied in full force on this album, and though the album falls short of Tumbleweed Connection, and was a general disappointment for me when I purchased it in late November, shortly after its November 5, 1971 release date, the album not only brims over with those strong Buckmaster arrangements and that strong musicianship from Elton, but from the contributions from a wide range of musicians including Rick Wakeman, Davey Johnstone, Chris Spedding, Herbie Flowers, David Glover and more. I listened to it about half a dozen times in very late 1971 and early 1972 and put it aside until just this week. It’s great to hear it on a much better stereo to appreciate the finer points, but still, it is likely I will again set it aside — good music, for sure, but still so much music I need to listen to!

Lighthouse: One Fine Morning

The Canadian jazz-rock group, Lighthouse, released their fourth and most commercially successful album, One Fine Morning, sometime in 1971, possibly around July or August of 1971. (Yes, another one I missed earlier.) The album is less pop and more solidly jazz-rock than their previous ones, with a number of strong tracks, including the opening track, “Love of a Woman”, “Sing, Sing, Sing” (Not related to the Benny Goodman classic), and the title track, “One Fine Morning”, which debuted on the Billboard 100 in the second week of September at position 75 and eventually ascended to the 24th spot. Plenty of good jazz-rock here with some more traditional rock content. Instrumentation includes trombone, saxophone, flute, trumpet and viola as well as guitar, piano and vibes.

Mahavishnu Orchestra: The Inner Mounting Flame

Formed in the summer of 1971, Mahavishnu recorded their first album in August of 1971, with Columbia releasing it on November 3, 1971. This album is a clear and unquestionable masterpiece combining jazz and progressive rock elements. John McLaughlin wrote all compositions on the album, and selected the band members from an international pool of talent (Czech-born Jan Hammer on keyboards, Panama-born Billy Cobham on drums, classically-trained American violinist Jerry Goodman when French violinist Jean Luc Ponty was not available due to immigration-related regulations, and Irish-born bassist and former McLaughlin bandmate from The Brian Auger Group.)

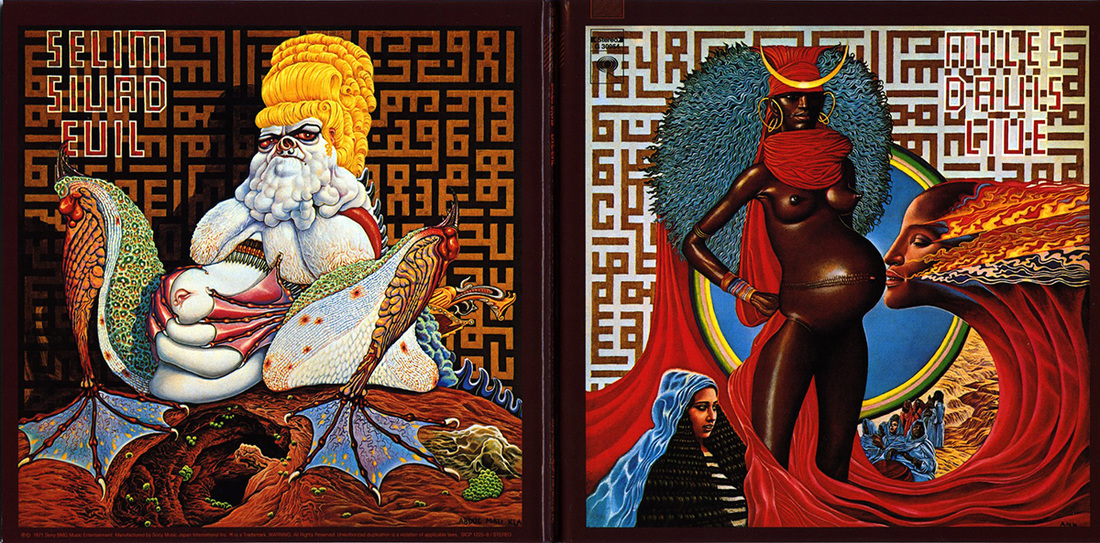

Miles Davis: Live-Evil

A bountiful 2 LP set of musical wonders with formidable front and back covers by artist Mati Klarwein (Santana’s Abraxis, Osibisa’s Heads, and of course, Bitches Brew) with the album containing both live material recorded on December 19, 1970 and studio material much earlier that year with the release date of the album on November 17,1971. The front and back cover are two sides of the dichotomy of beauty and ugliness (or perhaps more appropriate, beauty and anti-beauty) with the front headlining “MILES DAVIS LIVE” and the back proclaiming the reverse, or mirror image, as if seen from the other side of the album, “SELIM SIVAD EVIL.”

The fifteen minutes, four tracks, of studio material is rich, diverse and suitable for hours of exploration. Particularly interesting are the Hermeto Pascoal compositions with “Nem Um Talvez” being my favorite. For keyboard fans, it’s a real treat to get Keith Jarrett, Herbie Hancock and Chick Corea all at once.

The real treasure is the live material. Gary Bartz is great on both soprano and alto sax and the “electric” trumpet with wah-wah is a perfect vehicle for Miles Davis’s creativity and expressiveness. Jack DeJohnette is fantastic and creates magic with everyone, particularly Airto Moreira, Michael Henderson and Keith Jarrett. And then there is John McLaughlin, who shines in this material as much as in that first Mahavishnu Orchestra album.

It’s honestly a bit of a mess the way the live material is presented here due to the Ted Macero edits, perhaps well enough intended, but really throwing a wrench into the continuity and flow of the original performances. The best bet is to stream or pick up the 6 CDs of The Cellar Door Sessions 1970 to hear not only the original material used for this the bulk of this 2 LP Live-Evil release (edited from the sets that John McLaughlin sat in and represented in the fifth and sixth CDs) but the material for the earlier sets on the first four CDs.

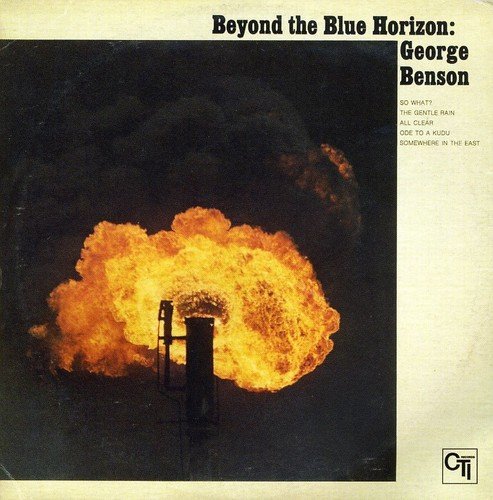

George Benson: Beyond the Blue Horizon

Any list of more than the twenty greatest electric guitarists that doesn’t have George Benson gets immediately discounted. He’s really is up there with the greats in terms of guitar technique and taste. This album may be casually classified as traditional post-bop jazz, but with two to three electric instruments on each track and Jack Dejohnette on drums, this is as much jazz fusion as any other albums of its time. Benson fares particularly well with his interaction with Hammond organist Clarence Palmer and DeJohnette is his usual incredible self. Ron Carter provides strong acoustic bass on track one, a particularly engaging rendition of Miles Davis’s “So What”, with funk and fusion elements from both Palmer and Benson. On track 2, “The Gentle Rain”, and track 3, “All Clear”, we have Carter on electric cello far exceeding the effectiveness and expressivity of at least 95% of contemporaneous rock guitarists. The third, fourth and fifth tracks are all Benson compositions with “Ode to a Kudu” relaxing and lyrical, and “Somewhere in the East” pushing out to more progressive and world music territory with a couple of additional percussionists added.

Herbie Hancock: Mwandishi

Another album I missed mentioning, released around March 1971, is Herbie Hancock’s second of his series of three Warner Brother albums, Mwandishi. It is yet another album that dedicates an entire LP side to one track, with the first side containing two contrasting works, the first of which, “Ostinato”, is an imaginative execution of improvising over an repetitively deployed musical pattern and brimming with that special class of rhythmically displaced jazz-funk championed by Herbie Hancock with Eddie Henderson shining on trumpet and Hancock on Fender Rhodes piano. The second track is true to its name, “You’ll Know When You Get There”, musically evocative of the sensation of being on leisurely journey, casually extended — the flute solo fitting in very nicely with the overall mood. The last track, taking up the second side, also provides music befitting it’s title, “Wandering Spirit Song”, with a strong Julian Priester trombone presence that carries into the free jazz section giving us a rough ABA form. Hancock provides compelling contributions on electric piano.

Kinks: Muswell Hillbillies

Released November 24, 1971, is the Kinks fourth (or fifth, if one counts the soundtrack album, Percy) concept album. Musically, there are no stand out tracks, but as a cohesive whole and faithfulness to the overall concept, the album works very well creating an overall experience that transcends the lack of memorable musical content, relying on the more memorable imagery, the well-crafted lyrics, Ray Davies’s distinct characters, Ray Davies’s vocal delivery to convey their viewpoints, and the generally creative and strong musicianship that lifts the more ordinary musical material.

Billy Preston: I Wrote a Simple Song

Released on November 8, 1971, I Wrote a Simple Song, is Billy Preston’s sixth studio album with Preston no longer on the Apple label but now with A & M. A soulful and rhymically lively album, it far exceeds allmusic.com’s two star rating, surpassing in quality most of the albums that allmusic.com rates as three or four stars. With some arrangements courtesy of Quincy Jones, George Harrison on guitar, and Preston’s expansive presence on piano, organ and vocals this album is a true joy to listen to.

John Martyn: Bless The Weather

Released in November, 1971, John Martyn delivers a very strong acoustic folk-rock album. Though I focus much more on music then lyrics, I’m still rather taken by the sentiment of the lyrics of “Let the Good Things Come” particularly lines like “I wish I had walked down, every road I ever set my eyes upon” and “I wish you could get through, to every face and every friend I ever knew.” Album is excellently engineered with quality musicianship. Strongest tracks include the jazz-tinged “Walk to the Water”, “Back Down the River”, and the sparkling instrumental, “Glistening Glyndebourne.”

Faces: A Nod Is As Good As a Wink… to a Blind Horse

Though perhaps my least favorite album mentioned in this post, despite ubiquitous presence in college dorm-room record collections during the early seventies, this third Faces album, A Nod Is As Good As a Wink… to a Blind Horse, released Nov. 17, 1971, is better than the previous two, partly due to Gus Dudgeon’s involvement and partly due to its shorter length, but mostly due to the exceptional last track, “That’s All You Need” and Ronny Wood’s near-historic guitar work on that same composition, and, to a lesser extent, Wood’s playing on “Stay with Me”, a song with such overtly sexist lyrics that current public sensibilities would probably exclude it from release today. Also worth noting is the brilliant and effective punctuation provided by use of the steel drum on “That’s All You Need.” Rod Stewart vocals are generally good, particularly on “Stay With Me” and “That’s All you Need”, and particularly when compared with the Ronnie Lane lead vocals on three of the album’s nine tracks.

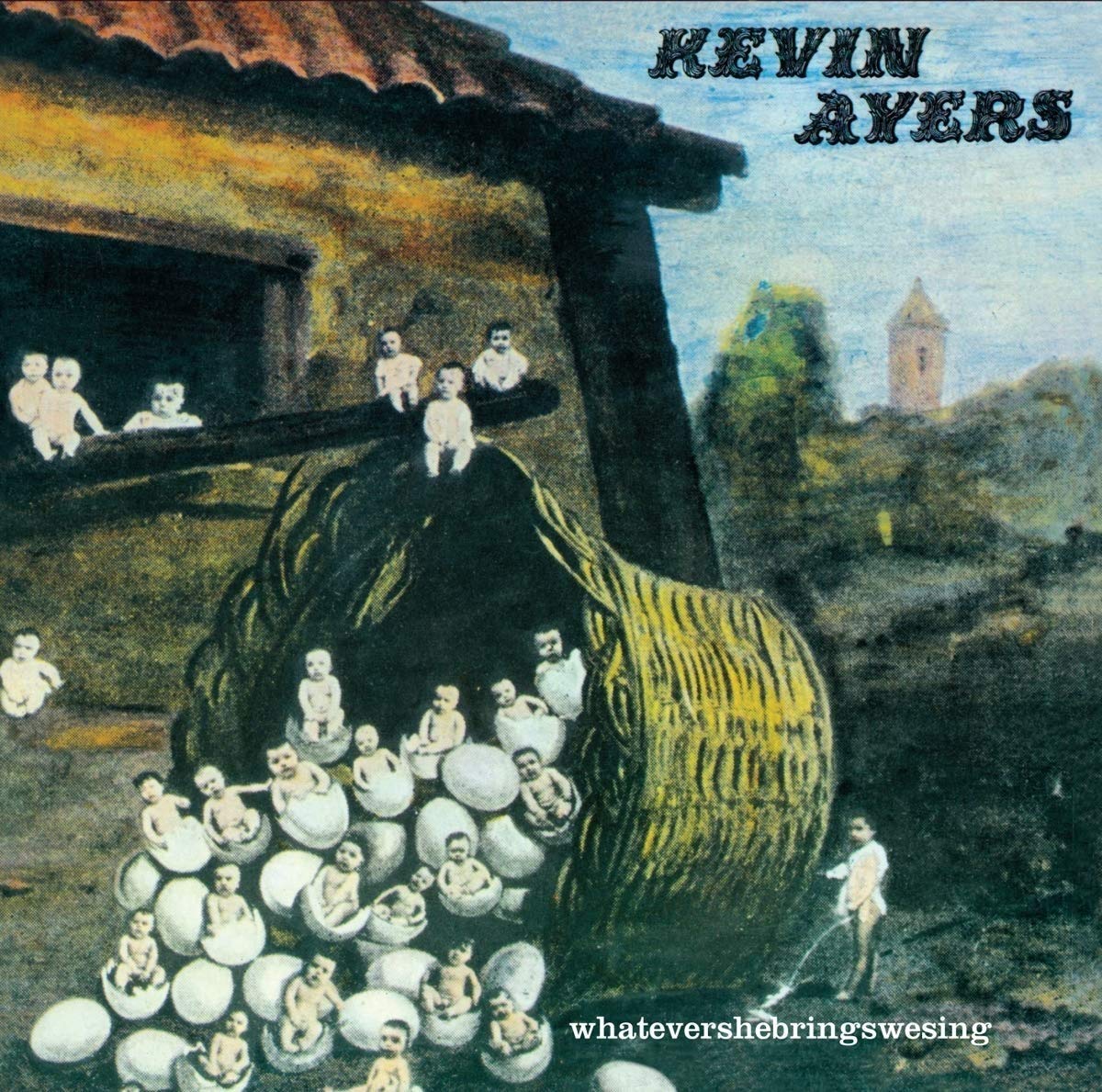

Kevin Ayers: Whatevershebringswesing; Laura Nyro: Gonna Take a Miracle; War: All Day Music; Carly Simon: Anticipation; Isaac Hayes: Black Moses; Status Quo: Dog of Two Head; Happy End: Kazemachi Roman; Alice Cooper: Killer; Sweet: Funny How Sweet Co-Co Can Be; Humble Pie: Performance Rockin’ at the Fillmore; Earth, Wind and Fire: The Need of Love; Harry Nilsson: Nilsson Schmilsson; Billy Joel: Cold Spring Harbor; Barclay James: Barclay James Harvest and Other Short Stories; Mott the Hoople: Brain Capers; Steppenwolf: For Ladies Only; David Axelrod: Rock Messiah

Clearly not enough time to cover all the good and great albums released in November 1971!!! Allow me to continue to stretch your patience and mention a few more.

In November of 1971, both Status Quo and Alice Cooper provided hard rocking albums with Alice Cooper’s Killer containing the classic hard rock hit, “Under My Wheels.” Harry Nilsson released Nilsson Schmilsson, his most commercially successful album opening with the upbeat and bouncy “Gotta Get Up” and a hit cover of Badfinger’s “Without You.” Sweet released their debut album, Funny How Sweet Co-Co Can Be, but it is more sugary bubblegum pop than glam rock, with glam rock becoming more popular and prevalent in 1972. Billy Joel’s first album, Cold Spring Harbor, with two strong tracks to start the album, was a sonic disaster with the album being unfathomably mastered as a faster speed, raising Billy Joel’s vocal range and timbre and causing all the music to sound rushed. Very puzzling how it got out the door as it clearly is sped up. The remix from 1983 also has issues, truncating the end of the strongest track. “You Can Make Me Free” and, apparently, not quite slowing down the music to the proper speed and pitch.

My friend that lived next door had two brothers, also my good and treasured friends, but not as close in musical preferences. One of them, the youngest of the three boys in the family and born 9 days earlier than I, was a fan of Moody Blues, CSN/CSN&Y (collectively and individually), and Humble Pie, and though I was glad to record his and one of his friend’s Moody Blues and CSN&Y-related albums, I never much took to Humble Pie, and though I never borrowed Humble Pie’s Rockin’ At The Filmore, I did get to hear it when visiting, and even when relistening to it almost half a century later, I have to admit that I still don’t take to either the music or the musicianship. Another album not on my favorite’s list is David Axelrod’s Rock Messiah. Because it is a mix between classical, rock, jazz, I would have bought it when it first came out, except for a scathing review of it in the L.A. Times. Nonetheless, a few years later, when I had ample spending money from teaching piano lessons and consulting at the computer lab, I did purchase it, and found it had its moments but only listened to it once — listening to it again, it doesn’t particularly resonant — overall, not wildly bold, creative, or innovative and nothing that entreats one to listen to it once again.

Laura Nyro released her fifth album, quite soulful and expressive and exclusively covers, each and every one imbued with Nyro’s finely detailed and exquisitely crafted interpretation — plus the addition of Labelle! Kevin Ayers released his third solo album, whatevershebringswesing, full of creativity and generally within the fairly wide progressive rock boundaries, with orchestrations, great musicianship (fellow Gong band members, if you consider Ayers an honorary member of Gong), and a wide range of vocal contributions from Ayers, including a commendable Vincent Price impersonation on the appropriately spooky “Song from the Bottom of a Well.”

It’s really worth recapping how lucky music lovers were in 1971, with all these great releases in November 1971. At this point there was not only great rock, progressive rock, and new jazz coming out, but we also had the latest revival of ragtime picking up steam, the emphasis on original performance practices in classical music, the ever-increasing popularity of baroque music and the corresponding issuing of recordings of a wider range of baroque composers. Beethoven’s 200th birthday in 1970 brought new recordings of Beethoven and one’s choices and access to riches in the public and university libraries was greater than ever. Living in the greater Los Angeles area provided a wealth of variety on FM radio with two full time classical stations, readily available jazz music, folk music from Eastern Europe on Sundays, and full albums played on some of the FM rock stations. And, contrary to the predictions of some of the adults of older generations, this new music of the late sixties and early seventies was not a transient fad or flash in the pan, but was lasting, enduring music — music that generations today still listen to via streaming, or in some rare cases, by purchasing original or re-issued LPs. Today’s easy accessibility of the music of all eras means that I don’t very often reach back into the catalog of the music of the 1960s and 1970s, but when I do, there is always plenty to enjoy!

Woodstock: Aug 16-18

Woodstock: Aug 16-18