Fifty Year Friday: The Canterbury Scene: Soft Machine and Caravan first albums

Establishing the starting point of progressive rock is a hopeless cause since elements of progressive rock appear in bits in pieces long before a general progressive rock style. The best one can do is try establish the earliest date of the first progressive rock group. Some might argue that such an “earliest date” is established by the formation of the Wilde Flowers, a group of jazz-leaning musicians that took a crack at British Rock and Roll in 1964 and developed a more-or-less accessible, and even partly danceable style of music that foreshadows the music of the Canterbury scene — easily enough explained by the members of the Wilde Flowers all taking prominent roles in these later groups. Though no albums were recorded, we have a set of demos that have been released on CD and are currently available on You Tube. Keep in mind that these were demos and not particularly representative of Wilde Flower live performances, which included some jazz-based improvisation.

Though I prefer to keep my distance from the term “progressive rock” as a label for a style of music, I support a concept of progressive rock representing the pushing of boundaries of status-quo music and breaking free of the constraints of commercial expectations, particularly when commercially successful as in the case of songs like the Queen’s “Bohemian Rhapsody.” This means that any rock music, whether by the Beach Boys, the Beatles, Jefferson Airplane, The Doors, The Zombies or some other group from the mid or late sixties that goes past the minimal expectations of pop/rock to explore the passageways that naturally and unnaturally twist and spiral out into Robert Frost’s road not taken. This is also why I am hesitant to consider some of the “neo-progressive” rock bands as notably progressive — such a use of the “progressive” label creates the ironic condition when applied to today’s musicians, of being indicative of a lack of progressiveness as they are trying to recreate an older style as opposed to pushing out to new territories. However, that said, quality and excellence is a more welcome and appealing feature in any music over progressiveness for the sake of sounding or being progressive. I will more readily listen to the post-romantic British symphony composers of the early twentieth century over many of their contemporary atonal composers.

The Wilde Flowers

Band members included, at various times:

- Hugh Hopper – bass, alto saxophone (died 2009)

- Robert Wyatt – drums, vocals

- Kevin Ayers – vocals (died 2013)

- Graham Flight – vocals

- Richard Sinclair – rhythm guitar, vocals

- Pye Hastings – guitar, vocals

- David Sinclair – keyboards

- Richard Coughlan – drums (died 2013)

- Brian Hopper – lead guitar, alto saxophone, vocals

The Soft Machine: The Soft Machine

The Soft Machine, named after the 1961 novel by William S. Burroughs (titled based on the nature of the human body) started as a quartet in 1966 that included Robert Wyatt and Kevin Ayers from the Wilde Flowers, and classically-trained keyboardist Mike Ratledge and guitarist Daevid Allen from the free-jazz group Daevid Allen Trio. Following a European tour in August 1967, Allen, an Australian, was refused re-entry into Britain due to a previous overstay on an earlier visit. Allen returned to Paris, to later form the group Gong, leaving Soft Machine a trio. On the first Soft Machine album we also have Brian Hopper and Hugh Hopper, prior members of The Wilde Flowers, appearing in the writing credits.

This first Soft Machine album is a mixture of psychedelic rock and jazz elements as in tracks like “Joy of a Toy”, based on “Joy to The World” and sounding more like early space rock than Christmas music. Robert Wyatt makes up for any shortcomings as a vocalist with his contributions on drums.

Interestingly, the post of this first Soft Machine album on YouTube (link) has a Dislike to Like ratio of .0257 in the same ballpark of the Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers (link) ratio of .0254 — compare that to the Beatles’ Abbey Road ratio of .15 (link) or Gentle Giant’s Free Hand of .030 (link)

Track listing [from Wikipedia]

| Side one | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 1. | “Hope for Happiness” | Kevin Ayers, Mike Ratledge, Brian Hopper | 4:21 |

| 2. | “Joy of a Toy“ | Ayers, Ratledge | 2:49 |

| 3. | “Hope for Happiness (Reprise)” | Ayers, Ratledge, B. Hopper | 1:38 |

| 4. | “Why Am I So Short?” | Ratledge, Ayers, Hugh Hopper | 1:39 |

| 5. | “So Boot If At All” | Ayers, Ratledge, Robert Wyatt | 7:25 |

| 6. | “A Certain Kind” | H. Hopper | 4:11 |

| Side two | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

| 7. | “Save Yourself” | Wyatt | 2:26 |

| 8. | “Priscilla” | Ayers, Ratledge, Wyatt | 1:03 |

| 9. | “Lullabye Letter” | Ayers | 4:32 |

| 10. | “We Did It Again” | Ayers | 3:46 |

| 11. | “Plus Belle qu’une Poubelle” | Ayers | 1:03 |

| 12. | “Why Are We Sleeping?” | Ayers, Ratledge, Wyatt | 5:30 |

| 13. | “Box 25/4 Lid” | Ratledge, H. Hopper | 0:49 |

The Soft Machine

- Robert Wyatt – drums, lead vocals

- Mike Ratledge – Lowrey Holiday De Luxe organ, piano (on 13)

- Kevin Ayers – bass, lead vocals (on 10 and 12), backing vocals (on 7 and 9), piano (on 5)

- Additional personnel

- Hugh Hopper – bass (on 13)

- The Cake – backing vocals (on 12)

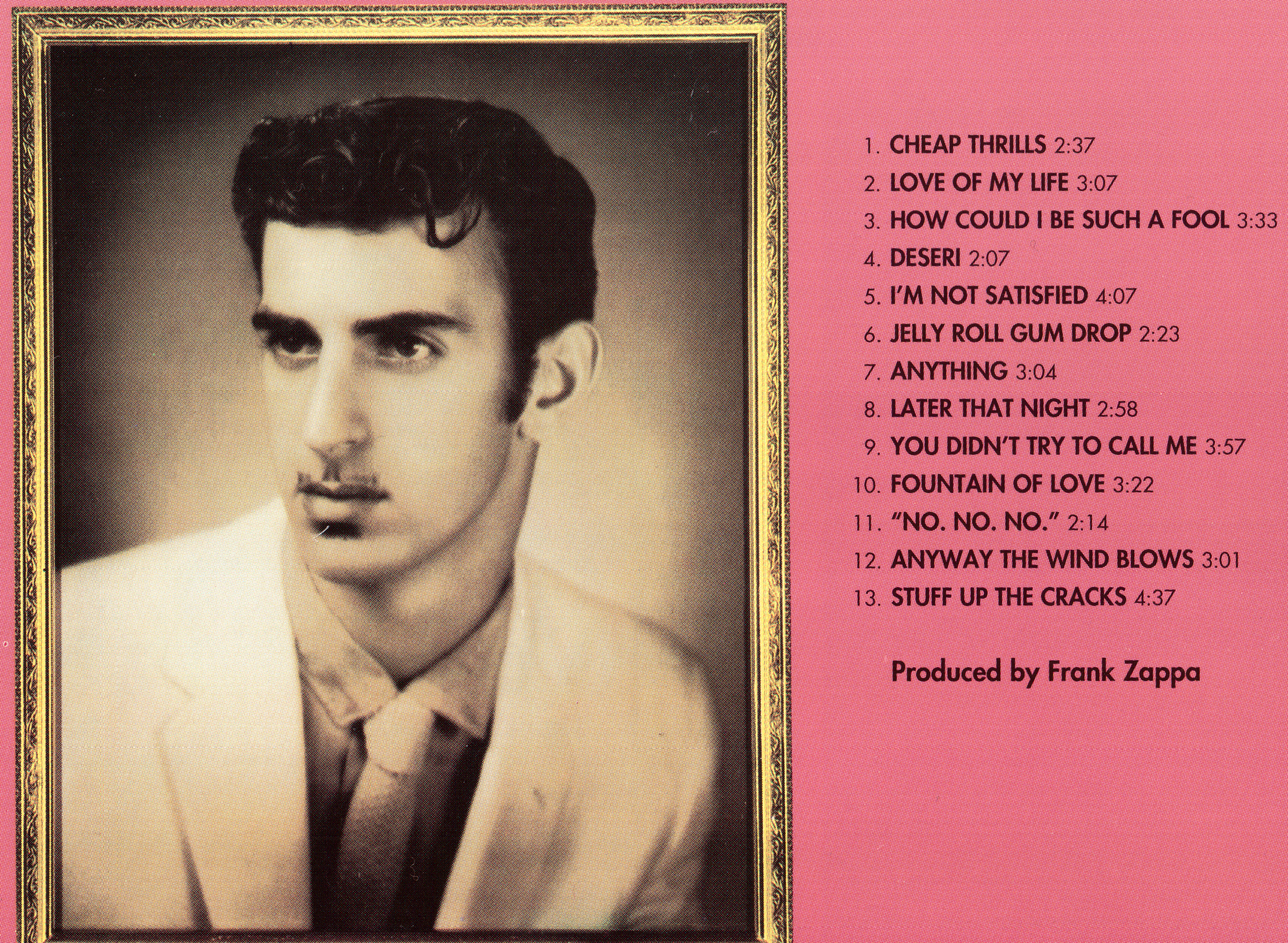

Caravan: Caravan

Also made up of band members from The Wilde Flower (Pye Hastings, David and Richard Sinclair, and drummer Richard Coughlan), Caravan started up in 1968 and released their first album about the same time as Soft Machine’s first album. This would be the first British group signed to Verve records, the famed American Jazz label founded in 1956 by Norman Granz that not only carried the most jazz titles in their catalog of any label, but also was home to Frank Zappa and The Velvet Underground.

Even if one is able to somehow dismiss the first first two Nice albums or the first Soft Machine album as qualifying as fitting into the progressive rock genre classification (once again, I am making a distinction between between being considered progressive rock music and being classified under the prog-rock label), it is much more difficult to dismiss this first Caravan album. It is unfortunate that the balance and mixing of this album is dodgy at best, but the music more than compensates for this otherwise serious failing.

“Place of My Own” with its alternation between the dreaminess of impressionism and the insistent forward progress of a march creates a whole organic work of four minutes that is comparable in substance to a similar length classical or jazz track. With liberal use of keyboard arpeggios and emphasis on the instrumental section over the lyrics, Caravan creates an overall mood and character to the entire work giving it is own identity as effectively as bands like Yes and Genesis would do to many of their songs on their early albums. This is followed by the Indian-influenced instrumental, “Ride”, the effective forward-moving and sometimes beautiful “Love Song with Flute”, and the quirky, mostly psychedelic Cecil Rons. ” However, the most notable piece is the nine-minute “Where but for Caravan Would I” which is co-written by Caravan and Brian Hopper (who also co-authored some of the tracks on the first Soft Machine album.) It is epic in nature, starting off with a relatively simple section, repeated, that modulates to a short contrasting section that quickly returns to the original section again before breaking out into a furious instrumental section dominated by organ that again returns to the original key and the altered and more intense original theme, which is followed by a more complex rhythmical section that nicely functions as the coda to bring the work to a satisfying and complete conclusion. This is a template for the prototypical prog-rock track, laid bare without any unnecessary frills or complications, something easily grasped and enjoyed, and available to be copied with endless variation and development. Yes, later groups would move well beyond this, but Caravan provides the necessary starting point — and though it may not so much have influenced other groups as much as it was just an instance of the parallel development of the post-psychedelic rock groups that got their start at the end of the late sixties, it is as an impressive example of the relentless nature of this new music to carve out its own language and means of expression from the available languages and expressions readily available in the diverse music of that time.

Track listing [from Wikipedia]

All tracks credited to Sinclair, Hastings, Coughlan & Sinclair except “Where but for Caravan Would I?” which is written by Sinclair, Hastings, Coughlan, Sinclair and Brian Hopper.

- Side One

|

# |

Title |

Length |

|---|---|---|

|

1. |

“Place of My Own” |

4:00 |

|

2. |

“Ride” |

3:41 |

|

3. |

“Policeman” |

2:45 |

|

4. |

“Love Song with Flute” |

4:09 |

|

5. |

“Cecil Rons” |

4:05 |

- Side Two

|

# |

Title |

Length |

|---|---|---|

|

1. |

“Magic Man” |

4:01 |

|

2. |

“Grandma’s Lawn” |

3:23 |

|

3. |

“Where but for Caravan Would I?” |

9:01 |

-

Caravan

- Pye Hastings – lead vocals (side 1: 1-2, 4), co-lead vocals (side 1: 5 & side 2: 1, 3), guitars, bass guitar

- Richard Sinclair – lead vocals (side 1: 3 & side 2: 2), co-lead vocals (side 1: 5 & side 2: 1, 3), bass guitar, guitar

- Dave Sinclair – organ, piano

- Richard Coughlan – drums

Side Note:

Interestingly, the post of this first Soft Machine album on YouTube (link) has a Dislike to Like ratio of .0257 in the same ballpark of the Beatles’ Sgt. Peppers (link) ratio of .0254 — compare that to the Beatles’ Abbey Road ratio of .15 (link) or Gentle Giant’s Free Hand of .030 (link)

Caravan’s first album Dislike to Like Ratio on Youtube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bt1inf8CRnE&list=PLALZtwXPtUFKvbI7h8Fc5CdqRYoI_qyyd) is .0028 — or 356 likes to only one Dislike — rather unheard of in youtube land.