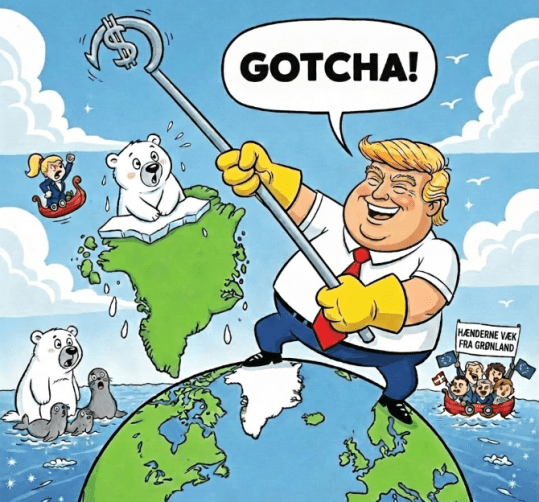

Grēnland unfæst (Greenland off-balance)

The Greenland saga continues to intensify, and this Zumwalt poem addresses the latest escalation of targeted tariffs, contrasting the gravity of the situation with a bit of humor. Given the history of Greenland with its European associations going back to the 10th century, Zumwalt chose a poetic style common to English speakers of that era: Anglo-Saxon alliterative meter.

“Grēnland unfæst” is the latest published Zumwalt poem, published today at New Verse News: https://newversenews.blogspot.com/2026/01/grenland -unfst-greenland-off-balance.html

This is the third consecutive month that Zumwalt has had a work published at New Verse News and the second day in a row a Zumwalt poem has been published in a literary journal.