Fifty Year Friday: Donovan, John’s Children and David Bowie

DONOVAN

Though it was not a short drive, on a few occasions in the mid seventies, a group of us, consisting of a consistent core of four, along with two or three additional participants, rode in one van and, sometimes, an extra car, from Southern California to Las Vegas to see a concert. For one particular trip we went to see Yes, and the opening act for them was the Scottish singer/songwriter Donovan Leitch, simply known as Donovan.

We were comfortably seated in the mid-size Aladdin Theater for the Performing Arts , when Donovan walked on the stage, by himself, carrying an acoustic guitar. Having purchased a few of his albums when I had been much younger and having grown up hearing his music as part of the sixties listening experience, I was intrigued to see him perform. Not so apparently with many in the audience that were here to see Yes. At one point, one of my fellow passengers, a generally great guy and skilled guitarist, shouted to the stage (we were quite close and had good tickets) for Donovan to finish quickly and leave. There was not much crowd noise and I suspected that Donovan could hear him as well as some of the other voices in the area expressing the impatience.

“That’s not right”, I told my friend. “He’s did a lot in the sixties”

“Well, it’s time for him to move on” was the reply.

And, if on cue, Donovan sang just one more song and then left. It was very sad. I had made the mistake of buying his 1973 Cosmic Wheels album when it had been released, hoping for the best and getting something closer to the opposite, and I was under no illusion that his best days were over, but I respected some of what he had done earlier, and appreciated his contributions to the musical world I had grown up with.

The sixties, particularly 1966 and 1967, a time of great cultural and musical change, culminating not in the summer of love, but really, in the society of which we live today — a society far from all the hopes and dreams of the youth of the sixties, but, still, a society more tolerant of cultural and musical diversity than any time in history. Yes, many in today’s music industry as well as numerous “mainstream” fans don’t have a broad tolerance for musical diversity, but in terms of what is available to purchase and the range of musical styles one finds in music groups the world over, the musical freedom allowed and accepted today is greater than ever and owes much of this to what occurred in the sixties.

Classical music (also known as concert music or concert hall music) had seen an increasing velocity of change from Baroque to Classical era to Romanticism to Nationalism to various phases and flavors of Modernism until the accepted norm in the fifties was atonal and/or serial music: unmelodic, unpredictable and often classified as “experimental.” The level of sophistication expected from the listener for this newer music created such a divide that most music presented to concert audiences were “favorites” or “war horses” from decades or one or two centuries earlier; the more modern music was relegated to college campuses, relatively small music venues, or, when part of traditional concerts, as small samplings or token works inserted into the regular season’s program schedule as almost a symbolic gesture of musical tolerance.

Jazz had undergone even more rapid changes in its short time span, borrowing from blues, marching music, written ragtime, foxtrots, and other sources to give us improvised music, first in small groups, then larger bands, and then with the advent of bebop, more emphasis on small groups again, with further changes in the 1950s incorporating influences from around the globe and classical music — expanding the various forms of jazz. Hard Bop, Free Jazz, Third Stream and other styles pushed the level of sophistication required from the listener so much so that contemporary jazz audiences grew smaller and smaller.

Early twentieth century blues had evolved into a louder, grittier, more public style, spawning jazz music based on blues progressions, boogie-woogie, jump blues, Texas and West Coast big band blues, Chicago blues, classic rhythm and blues, Rock and Roll, and British rhythm and blues.

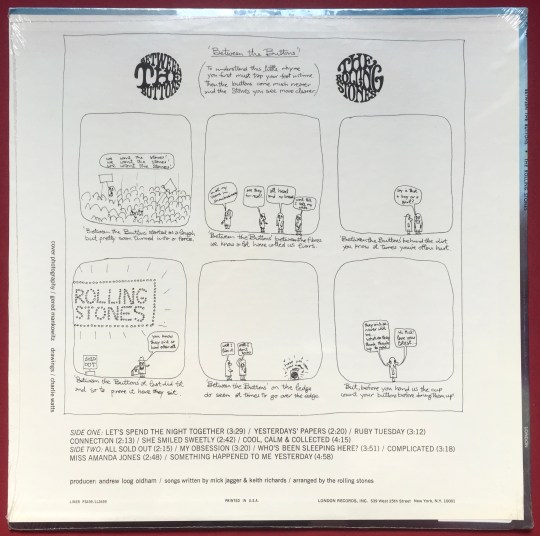

Most of the bands that came to the forefront by the mid 1960s (Animals, Yardbirds, Rolling Stones, Pretty Things, Spencer Davis Group, Manfred Mann, and to a large degree even the Beatles and Kinks) either started as blues-based bands or were formed by former members of such bands. The most successful of these British Bands developed their own personalities and style, abandoning blues progressions and incorporating multiple musical influences into their music. American bands were then influenced by the British as well as incorporating folk and country music influences. By 1967 we were seeing many of the best groups having their own sound, producing music that was not quite like any other music or other groups, and, more notably, not static but changing significantly from album to album.

Popular music in 1967 is often eclectic, groups learning from each other, borrowing elements from American Folk, Indian Classical, Jazz, Ragtime, Free Jazz, Western Classical, American Country, Gaelic, English Music Hall and the Caribbean.

Early Donovan was influenced by Bob Dylan, both musical and lyrically. As Donovan forged his own identity, he also borrowed from contemporaries, incorporating Indian and Near East influences into his music and, as with many bands and performers, created a final product in partnership with the producer. Donovan’s best albums, “Sunshine Superman”, “Mellow Yellow”, and “Hurdy Gurdy Man”, (and unfortunately one of his worst, “Cosmic Wheels”) were produced by Micky Most, a very singles-oriented, short song producer.

In 1967, Donovan had his own sound, was an influence on others, and was relatively popular. Donovan’s “Mellow Yellow” album was released in March 1967 and included the hit song “Mellow Yellow” which reached the number two spot on the Billboard 100 in late 1966. The era of sex, drugs and rock and roll was underway, and the lyrics of Mellow Yellow” align with such a culture: “mellow yellow”, “electrical banana”, and “wanna high forever to fly” which one can interpret as drug references (those of us from the era remember the myth of smoking banana peels), or more accurately interpret as sex references (as later explained by Donovan — mellow yellow being a model of a vibrator), making this a love song from a vibrator to a young lady named Saffron. What may be more interesting, at least musically, is how Donovan accents the word “electrical” to fit the melody’s rhythm, something we see as a particular Donovan trait from this era — whether that is intentional or just his forcing words to fit the music. “Epistle to Dippy”, which got to #19 on the Billboard chart around February 1967, also takes liberties with accents not only with “crystal spectacles”, “paperback” and “suspicious” but between modifiers and nouns as in “over dusty years, I ask you” sounding like “over dusty, years I ask you.” One may miss this if not listening to with the lyrics. I can’t currently find a youtube video that display the lyrics with the music, but below are the lyrics and its worthwhile to follow them along with the song:

“Epistle To Dippy”

See the young monk meditating rhododendron forest.

Over dusty years, I ask you

What’s it’s been like being you?Through all levels you’ve been changing,

Getting a little bit better, no doubt.

The doctor bit was so far out.

Looking through crystal spectacles,

I can see I had your fun.Doing us paperback reader,

Made the teacher suspicious about insanity;

Fingers always touching girl.Through all levels you’ve been changing,

Getting a little bit better, no doubt.

The doctor bit was so far out.

Looking through all kinds of windows,

I can see I had your fun.

Looking through all kinds of windows.

I can see I had your fun.Looking through crystal spectacles,

I can see I had your fun.

Looking through crystal spectacles,

I can see I had your fun.

Such a tiny speculating whether to be a hip or

Skip along quite merrily.Through all levels you’ve been changing:

Elevator in the brain hotel.

Broken down, but just as well.

Looking through crystal spectacles,

I can see I had your fun.”

This song is not on the original “Mellow Yellow” album but on the current CD as a bonus track.

In October of 1967, Donovan recorded material for one of the first box sets in rock, “A Gift From a Flower to a Garden” with Donovan evidently being the flower and his audience a garden. The first record starts off with the enchanting “Wear Your Love Like Heaven” which eventually appears in cosmetic commercials including an “Eau De Love commercial with Ali MacGraw of “Goodbye, Columbus” and “Love Story” fame.

The first LP is a bit silly, but nicely melodic. The second LP, a little more serious in my mind, is an acoustic LP dedicated to children (“For Little Ones”) and perhaps it is more serious just because the children of that era were marginally more serious and responsible than many of the teenagers and young adults.

Though “Wear Your Love Like Heaven”, “Epistle to Dippy” and “Mellow, Yellow” far outshine any of other of Donovan’s songs on “Mellow Yellow” or “A Gift from a Flower” both albums are enjoyable, interesting, and worth listening to for both historical perspective and musical enjoyment. As a bonus one gets Paul McCartney on bass on some of the Mellow Yellow tracks, and one is exposed to a style of music that could simply be categorized as “Flower Power”, perhaps the musical equivalent of the contemporaneous philosophy of peace triumphing over the corrupt and violent aspects of social organizations and governments.

JOHN’S CHILDREN

Relatively unsuccessful, and called “positively the worst group I’d ever seen” by their own manager, Simon Napier-Bell, John’s Children qualifies as one of the more interesting groups of 1967 for many reasons.

First, they probably played as loudly, if not louder, as anyone at that time In fact, so loud and rowdy were they (including staged fights with fake blood capsules) that the Who dropped them as an opening act since they very effectively made the Who’s own onstage drama anti-climatic.

Second, in March 1967, the band replaces their previous guitarist with a relatively unknown, Marc Bolan, a London native with the dream of making it a singer-songwriter, like Donovan. Bolan, becomes the new guitarist at the request of Napier-Bell, the manager of Bolan and John’s Children as Napier-Bell believes this is a win-win situation for everyone. Marc arrives at the bands’s own club and rehearsal hall, John’s Children Club (in Leatherhead, Surrey southwest of London), with his acoustic guitar and a set of his own songs. Switching him to a borrowed Gibson SG the current members of the band rehearse through some of their current material, listen to Bolan’s music, leaving him to continue to play away at high volume on the Gibson.

Third, and I welcome any challenges to this contention, I believe the roots of Glam Rock can be traced to this band. I can make a somewhat shaky case for musical elements of glam in the Kinks, The Pretty Things, and Small Faces (traces of glam in the Rolling Stones come after John’s Children’s 1967 singles), but the glam elements one find in John’s Children are more remarkable. Yes, they were loud, violent at times, so much so they got kicked out of Germany, they were technically and musically unimpressive on their instruments (except for Marc Bolan) and the lacked any notable musical identity. But they had a outcast-type of independence, disdain for propriety, and unabashed attitude towards sex resulting in the Bolan-authored single “Desdemona” getting banned by the BBC for the phrases “Lift up your skirt and fly” and “Just because the touch of your hand can turn me on just like a stick”, naming a single “Not the Sort of Girl You’d Like to Take to Bed” (shelved by their label), and most notably, naming their first and only album “Orgasm” (which was stopped from being released with pressure from the Daughters of the American Revolution — at least until September 1970 when it was released with it’s title removed from the front cover and the LP label (but, perhaps accidentally, still visible on the thin outside spine of the cover.)

And so where was the glam? They didn’t wear eyeliner, they mostly adhered to mod cultural norms (which were transitioning to the psychedelic era), and they didn’t wear platform shoes or embrace sexual ambiguity.

Well, elements of glam are evident in several tracks of the pre-Bolan, “Orgasm” album, starting with the Napier-Bell/Hewlett “Smashed Blocked” track with its Queen-like ensemble vocals, the affected, seductive vocal that follows, the 1950’s ballad chord changes á la Bowie’s “Drive-In Saturday”, the alternation between chorus and solo á la the Tubes, the flirtatious tempo, and the overall general attitude. This is the first track on the 1982 Cherry Red LP, which, I believe, presents a more accurate version of the intended order of songs than the 1970-released White Whale LP. An interesting gimmick in play here is that the “Orgasm” album includes overlaid crowd-noise (dominated by screaming female fans) to make this sound like a live album, probably a wise choice given the general musicianship of the band.

The second track, “Just What You Want — Just What You’ll Get” continues to seem more glam than possible for 1967, with its tango and cabaret undertones and sexually unapologetic lyrics sounding like a cross between Alice Cooper and a song from “The Rocky Horror Picture Show”; the arrangement includes chorus backup that sounds like its coming from a cadre of male strippers. Some of this may be inferred with the advantage of a retrospective viewpoint, but there is no denying the sexual boldness and directness of the lyrics:

“Your hands and lips

Always know what I like to feel,

But don’t think I can’t see that

You’re trying hard to make me say I love you.

So what’s in it for me?

(backup singers singing “hey, hey”)

“You think that I should be crazy about you,

But I know what life would be with

Someone like you always hanging around me

So what’s in it for me?

(Chorus — lead vocal stage whisper with “hey, hey” and “buh, buh, buh” backup)

“Don’t think I don’t know just what you want – everything…

Don’t think I don’t know just what you’ll get – nothing!

What’s in it for me?

Don’t think I don’t know just what you want (just what you want)

Don’t think I don’t know just what you’ll get (just what you want, just what you’ll get)

“Leave me alone until you don’t wan’t to

Or come back, we’ll make your love worthwhile

What’s in it for me?

Don’t come around until you’ve thought of something that

find or use your luke warm smile*

What’s in it for me?”

(*lyrics unclear at start of line)

The sixth song, “Jagged Time Lapse” provides more of this nascent glam style with a liberal amount of breathy”aaahs.” There a several other tracks on the album, some like “Not the Sort of Girl You’d Like to Take to Bed” that are also of interest, though none of these other tracks provide any significant additional evidence to support my contention of this being the first glam album.

Note, again, that this album is before the band replaces Geoff McClelland with Marc Bolan.

:format(jpeg):mode_rgb():quality(90)/discogs-images/R-1643216-1387560051-7713.jpeg.jpg)

The band gets an upgrade at guitar with the addition of Bolan as well as some interesting songwriting contributions. At this point, Marc is mainly sticking to formula chord patterns but it’s fun to hear his vibrato-heavy vocals. One can get a more complete picture of this Bolan-era of John’s Children (brief as that is) in the 2013 2 CD set, “A Strange Affair”, which includes all tracks from “Orgasm” and several post-“Orgasm” tracks. The two CD set includes compositions by Bolan including “Hippy Gumbo” which foreshadows his upcoming Tyrannosaurus Rex work.

DAVID BOWIE

In 1967, very much under anyone’s radar, and already thirty-years old (a few months younger than Donovan and a few months older than Marc Bolan), David Bowie (replacing his real last name of Jones to avoid confusion with one the band member’s of the Monkees) releases his first album. Nothing here indicates even a slight trace of Donovan’s Flower Power, John’s Children early glam, the Beatles sophistication, the more advanced psychedelic tendencies of Pink Floyd, Jimi Hendrix, or the Doors, the rock and roll or rhythm and blues of the early sixties British Bands, the soul of Aretha Franklin, the progressive aspirations of fellow Deram-label Moody Blues, or much of anything currently pushing the musical envelope of the time. However, there are strong influences, musically and lyrically, from Anthony Newley and English Music Hall style. Bowie adds an offbeat twist to several songs, even more than we find from Newley or most English satire of this time. The level of lyrical craftsmanship is solid even if the melodies are unoriginal and forgettable. For a Bowie fan, music historian, or someone wanting to more completely understand Bowie’s range of skills, its worth exploring the David Bowie of 1967.

Previous Fifty Year Friday Posts:

John Coltrane/Jefferson Airplane

“With one stroke,” he wrote to his friend

“With one stroke,” he wrote to his friend

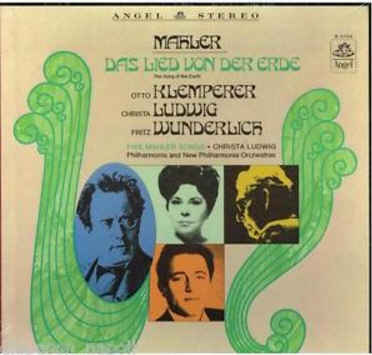

In launching a Google search for lists of Jazz albums of 1967, one finds lists like this that include many fine albums:

In launching a Google search for lists of Jazz albums of 1967, one finds lists like this that include many fine albums: