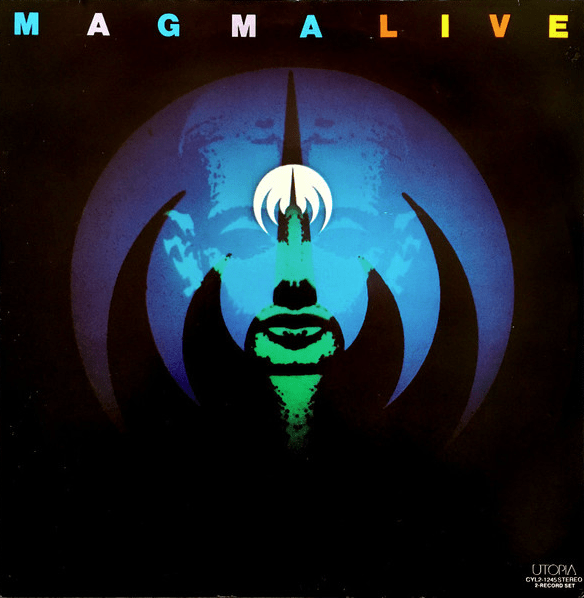

Queen, Joni Mitchell, Keith Jarrett, Magma, Vangelis, Chris Squire & more; Fifty Year Friday: November and December 1975

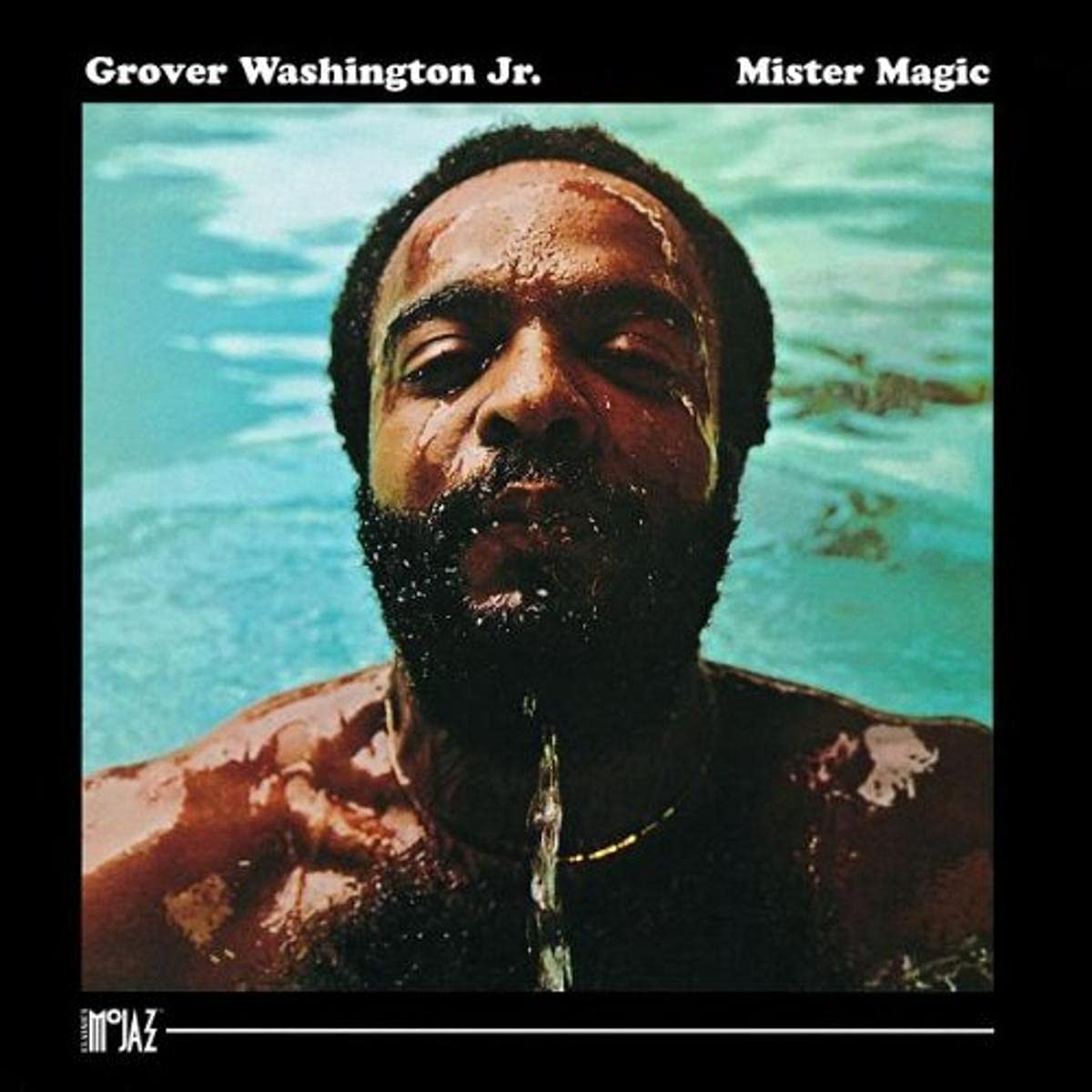

Queen: Night at the Opera

Released in November of 1975, Night at the Opera starts with the excitement of an ocean voyage — we hear arpeggiated waves from the piano, whale rumblings from the bass, bird cries and seagull squawks from multitracked guitar breaking into soft strains of a tango quickly turning into heavy metal. This is Freddie Mercury the composer at the height of his craft.

After having purchased three Queen albums already, the first thing I did when I brought this album home in December of 1975 was note which tracks were attributed to Mercury — this served as indicators to what tracks would impress me the most. That turned out to be an effective predictor, but, importantly, the rest of the band’s contributions were some of their very best songs, making this album packed with classic material from start to the pinnacle of the album, the penultimate track, “Bohemian Rhapsody” — one of those rare instances in rock since the Beatles had disbanded where a truly great work of music made its way from legendary status with serious listeners, musicians, and dedicated fans to legendary status with the general public, even though, perhaps as expected, it took some time to do so.

And just as the Beatles elevated their work with multi-track musical enhancements, so too did Queen elevate Night at the Opera to a precisely rendered set of cohesive numbers that deservedly live up to the album’s title. Now, don’t get me wrong — we have an amazing musical diversity on this album — with such diversity in just Mercury’s compositions — but we add to that “I’m in Love with My Car”, “You’re My Best Friend,” the vaudevillian “Good Company” with ukulele and outstanding guitar accompaniment, and “The Prophet’s Song” with its brilliant use of deceptively simple imitative counterpoint, and it’s pretty easy to understand how Night at the Opera more than holds its own today as a timeless classic.

Keith Jarrett : The Köln Concert

One of my favorite possessions was the triple LP Keith Jarrett Solo Concerts: Bremen/Lausanne which I had purchased with Christmas money in 1973. It was just incredible to have a three LP set of piano improvisation of such high quality. Given that, I am puzzled why I never bought The Köln Concert until the complete version made its way on to CD around 1984.

Recorded live in January of 1975, The Köln Concert was released in late November of 1975, the album starts off plaintively in the style of the quiet Americana reflectiveness so well done by classical composers like Aaron Copland and Roy Harris. For the first improvisation, Jarrett leans heavily on repetitive phrases and ostinato-like patterns to continue to move the music forward, flowing as if driven by stream of consciousness, yet always compelling and logical, deftly avoiding lingering too long in any single style, texture, or mode of emotional expression as the music logically unfolds.

The second piece, broken up onto three sides of the double LP album, is dramatically different in tone and character. Like the first improvisation, it evades any simple stylistic labels sometimes flirting into rock piano improvisation. Where the first improvisation was reflective, the second is inexhaustibly joyous and intensely rhythmically as Jarrett turns the piano into a percussive engine, hammering out a powerful, trance-like groove with his left hand that is pure, ecstatic energy. This propulsive marathon of invention continues through Part IIb, before finally dissolving and making way for the famous encore, “Part IIc.” After all the complex fireworks, this final piece is a moment of breathtaking, lyrical grace — a simple, hymn-like melody that releases all the tension and remains one of the most beautiful themes Jarrett ever played.

The music makes this performance legendary, but like the most interesting legends, it has an almost mythical backstory. Jarrett had specifically requested a Bösendorfer 290 Imperial concert grand. Unfortunately, what was made available on the stage was a baby grand rehearsal piano in such bad condition that Jarrett had initially refused to play on it. The requested piano was in storage and due to horrid weather was not able to safely replace the inferior piano. So Jarrett was forced to confront the rehearsal piano, an unsuitable, tinny, and out-of-tune practice piano he tested during the afternoon of the concert and was so dissatisfied with it he almost threw the towel in performing that evening. The promoter finally convinced him that he had a responsibility to play as best as he could for a sell-out crowd and somehow do his best to deal with the inadequacies of the inferior rehearsal piano. Jarrett went forward with the performance and it was this limitation, this ‘bad instrument,’ that forced Jarrett to navigate that evening’s improvisations into new territory, compelling him to avoid the shrill upper register notes and the weak lower bass notes, replacing the harmonic function of the latter with lower middle register accompaniment patterns and repetitive ostinatos — thus creating the distinctive style that unifies the music of this remarkable performance.

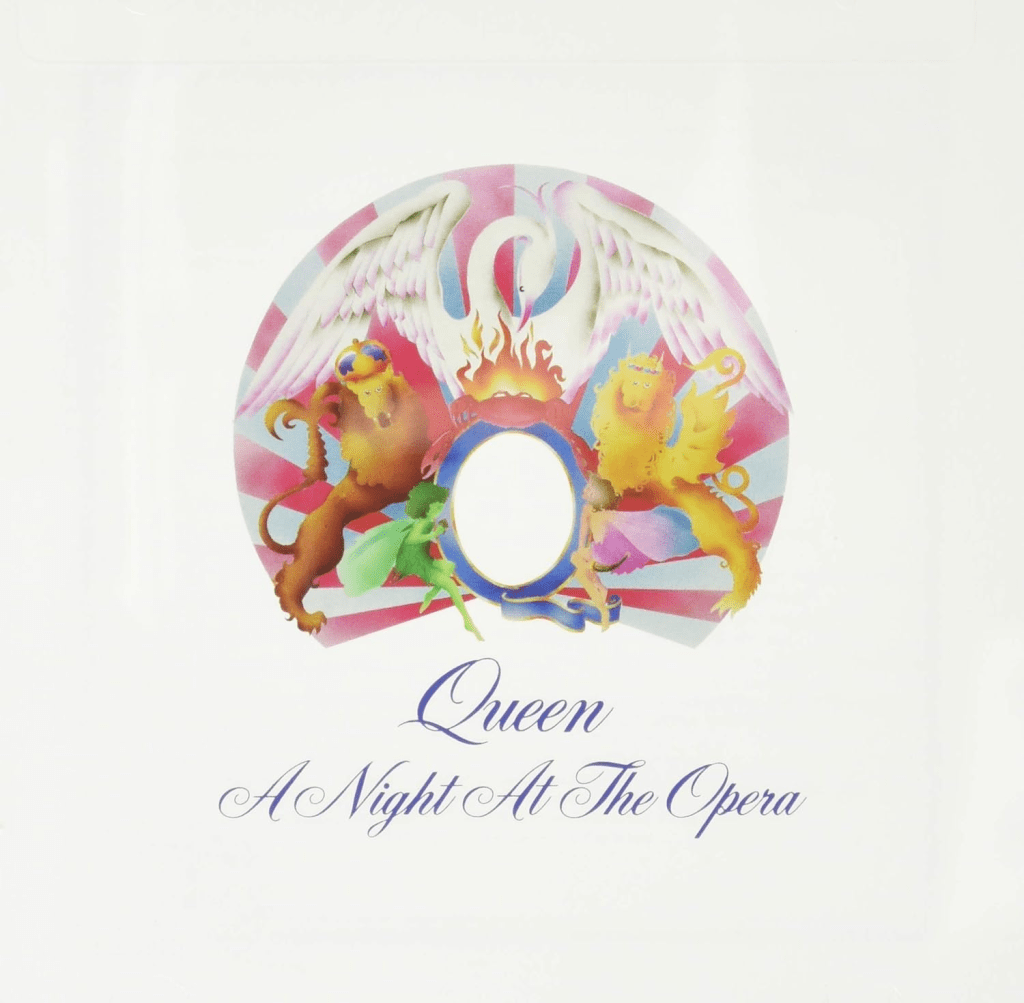

Joni Mitchell: The Hissing of Summer Lawns

Released in November of 1975, The Hissing of Summer Lawns finds Joni Mitchell presiding over one of the most seamless marriages of lyrics and music of the 1970s. The poetry here is evocative and ironic, crafting memorable metaphors and unforgettable images. It’s often said that when constraints are placed on artists, they often produce their best work. For an artist who had previously written music around pre-existing lyrics to then make that shift over to the craft of fitting words into already composed music, one might expect a change in character — or at least in lyrical texture. Beginning around 1973 or 1974, Mitchell’s lyrics indeed became more fluid, impressionistic, and engaged, so that by the time of this album, she had achieved a near-perfect fusion of music and poetry, with the music among her finest creations.

And how does one classify the sound? One cannot. It draws on pop, rock, folk, and jazz, yet it belongs to none of them. The album charts its own course, allowing space for stellar contributors like Bud Shank and Joe Sample to leave their imprint without overshadowing Mitchell’s vision. The closing track, “Shadows and Light,” brings the album to a transcendent conclusion: a multi-tracked a cappella choir of Mitchell’s voice against a contrasting, processed drone from a Farfisa organ. The result is a kind of sonic cathedral, where light and sound filter through like stained glas — ever shifting, quietly monumental, and filled with a sense of cosmic design.

The entire album is a showcase of extracting equilibrium from motion. The music is built on a strong foundation yet exploratory and liberating. Here we have an artist of the highest level in full command of her gifts, unafraid to blur the lines between song and painting, intellect and intuition. The Hissing of Summer Lawns continues to be an album worth returning to: we achieve familiarity with repeated listenings but never is the magic lessened.

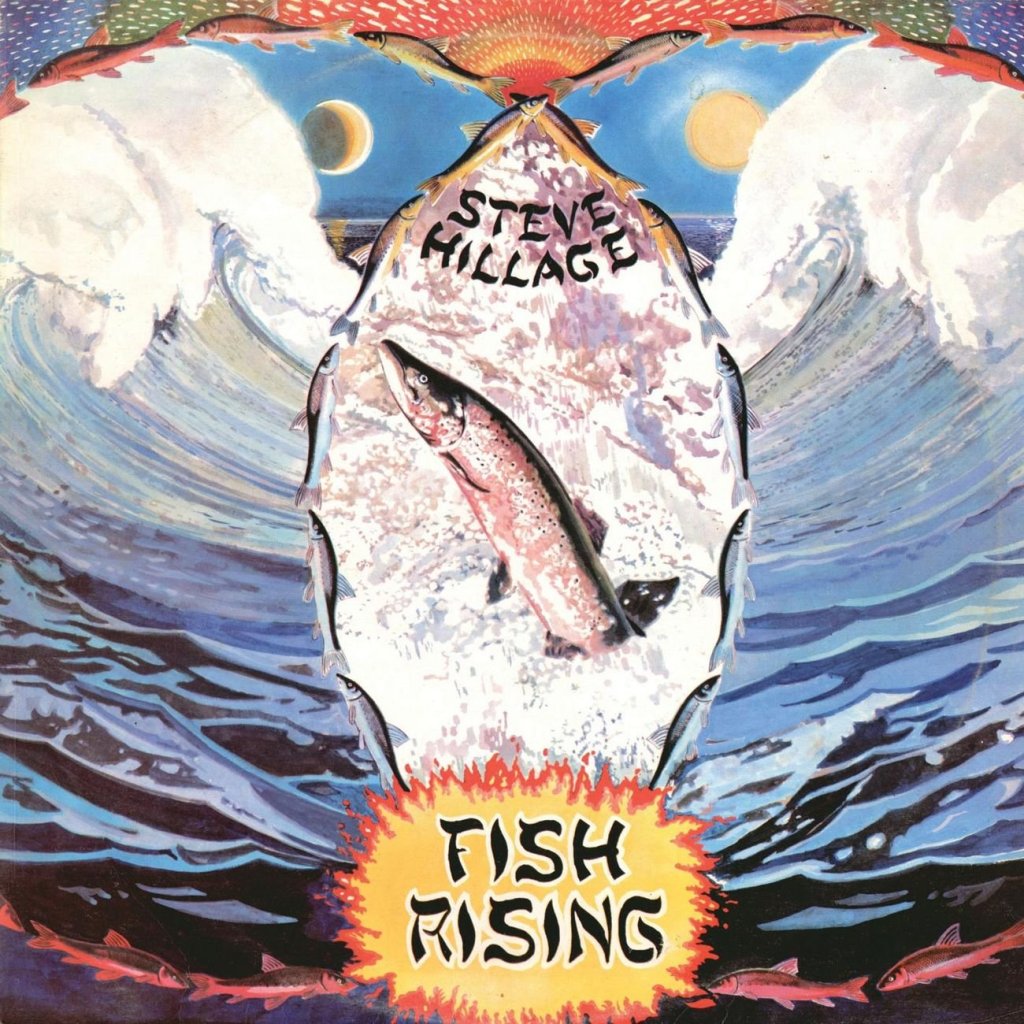

Chris Squire: Fish Out of Water

Another November 1975 release was Chris Squire’s highly accessible, melodic Fish Out of Water. For those like me who couldn’t get enough of the brilliance of Yes’s Fragile, this album was filled with the musical inventiveness and wonderful bass lines that dominated that Yes album. Musicians include Bill Bruford on drums and percussion, with saxophonist Mel Collins on two tracks and Patrick Moraz on bass synthesizer and organ on one track . Squire handles all the vocals, bass guitar, some acoustic twelve-string guitar and electric bass. Special compliments go Andrew Pryce Jackman who provides acoustic and electric piano keyboards and seamlessly integrated orchestration providing the album with additional depth and further contributing to its ebullient vitality. Fish Out of Water is a must-have album for all Yes fans surpassing most of their catalog released after 1975.

Crack the Sky: Crack the Sky

Crack the Sky’s debut was released in limited quantities in November 1975 by the independent label, Lifesong. Is this the biggest accomplishment by this label? Depends on your perspective — Lifesong posthumously re-released several greatest hits albums of Jim Croce material starting in 1976 as well as being responsible for “The Biggest Rock Event of the Decade” — that’s right — the rock opera Spider-Man: Rock Reflections of a Superhero — an album of such popularity that I cannot find any entry for it on Wikipedia, though in fairness, the title was released again twenty-five years later on CD and is currently available on eBay for $49.

Putting Spider-Man historical considerations aside, the Crack in the Sky album, despite its limited distribution, eventually climbed up to spot 161 on the Billboard Charts in February 1976 aided by some airplay in the Baltimore area and more importantly being identified by the Rolling Stone magazine as the debut album of 1975.

Keyboard player and lead vocalist John Palumbo wrote all the music and lyrics showcasing an eclectic range of styles incorporating sixties pop elements and contemporary progressive rock elements. Both the music and lyrics are generally quirky, with a tongue-in-cheek, often ironic, humor deeply embedded in the lyrics and the music rich with accessible melody. There are musical moments that recall surf music, the Beatles, Procol Harum, early Genesis, and even Gentle Giant. It’s not a particularly well-produced album but it is a lot of fun, and an album that anyone who considers themselves well-versed in the history of rock music should have heard at least once.

Tangerine Dream: Ricochet

Recorded in late October and early November of 1975 in England, partly live at Fairfields Hall in Croydon and partly in the studio, Ricochet was released in December of 1975. It continues that rhythmically intense sequencer-driven signature sound from Rubycon, delivering it with sparkling clarity and focus. The music unfolds logically with a strong sense of overall meaning and purpose, effectively locking in one’s attention and never letting it go. Side One, “Ricochet, Part One” contains studio improvisations and recreations of live performances with side two, “Ricochet, Part Two” being predominantly live.

Vangelis: Heaven and Hell

Released in November of 1975, Heaven and Hell is a mixture of the cinematic, early and modern “classical” music, Greek folk and some elements of progressive rock. The album effectively combines Vangelis’s mastery of synthesizer with orchestra to create a richly themed concept album about the duality of human interaction with good and evil, the light and the darkness of existence. Side One, “Heaven and Hell, Part I”, opens furiously with synthesizer and chorus setting a strong symphonic tone and concludes with vocals by Jon Anderson of Yes segmented with a glorious orchestral and synthesizer interlude. Side Two, “Heaven and Hell, Part II” opens up, contrastingly, darkly and ominously, generally maintaining that mood with the notable interspersion of an exuberant, infectious Greek-influenced folk-dance-like section and its more reflective ending. The musical tone-painting is particularly impressive, effectively supporting side two’s darker thematic premise.

Mike Oldfield: Ommadawn

Released in November of 1975, Ommadawn is Mike Oldfield’s third major symphonic work, following the partly Exorcist-driven phenomenon of Tubular Bells and the expansive, pastoral landscapes of Hergest Ridge. Ommadawn mostly consists of one long work, the title track, divided between the two sides of the original LP with a short additional work at the end. It is this title track that is the gem and centerpiece of the album, excelling in compositional presentation and development of thematic material with the first theme deftly varied, followed by an abruptly effective intrusion of the second theme around the 4:15 mark, which is also skillfully varied. After this exposition of fundamental material, both themes are further developed and extended with a richness of instrumental variety and occasional vocals (using a cleverly altered Irish translation of some simple English words) invoking a tribal sense of community.

The second half of “Ommadawn” is more dramatic with greater musical weight and contrast, further exploring a wondrous world-fusion sound that would soon become a whole sub-genre of music. The highlights here include Paddy Moloney on the Irish equivalent of bagpipes, more properly known as Uilleann pipes, and an uplifting blend of vocals and glockenspiel followed by an Irish-like dance section that brings the work to a close.

For those looking to check this album out, avoid the original mix and go for the sonically spectacular 2010 remix which provides significant clarification and enhancement of individual instruments and provides rich, immersive stereo.

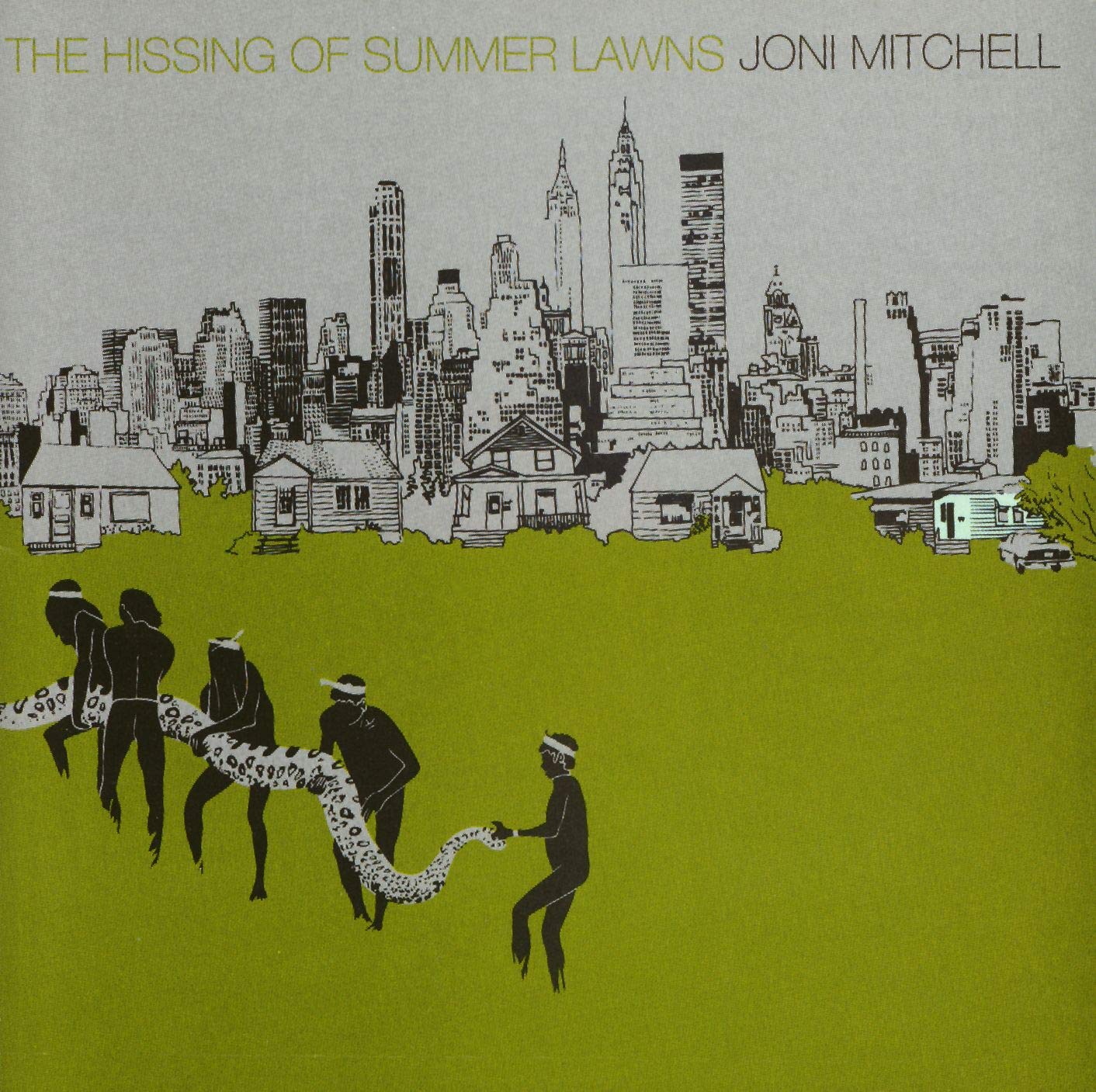

Magma: Live/Hhaï

Released in December of 1975, I bought this album in Germany in 1978, and I was not surprised in the least to find this live album of the French progressive rock group in Germany. Unlike Ange, which had a distinct French coloration to their albums, Magma had a Germanic sound and eschewed the French language to adapt a language more suitable to their music — not German, but — okay let’s break this down.

Christian Vander, son of French jazz pianist Maurice Vander, was born in Paris in 1948. Exposed to both jazz and classical music, he grew up listening to Wagner, Bach and Stravinsky and met several great jazz artists including Chet Baker, who gifted Christian Vander his first drum kit and Elvin Jones who shared his musical expertise. Vander brought all these influences as well as his intense admiration for a number of jazz giants, most particularly John Coltrane, as well as drummers like Art Blakey, Max Roach, Kenny Clarke and Tony Williams. Vander brought all such influences with him, including Coltrane’s searching musical intensity, when he founded Magma in 1969 as Magma’s leader, primary composer, drummer and an important contributing vocalist.

With the formation of Magma, Vander begin the creation of the mythology of Magma concept albums and the appropriate language — Kobaïan, the language of the fictional world of Kobaïa — a distant planet colonized by a group of humans fleeing earth’s moral and ecological collapse. The language’s main function was to provide the appropriate musical sound for Magma’s music and to represent a sacred language of renewal. Its sonic characteristics are starkly different than French, coming closer to Slavic and Germanic patterns, but intrinsically supportive of Vander’s musical ideas, which slowly coalesced into a dark, more teutonic, primitively spiritual style, with texture and timbral/orchestral characteristics eventually significantly influenced by Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana, which Vander first heard in 1972.

This 1975 Live/Hhaï album includes material as early as 1973, all of which represents the mature, dramatic Magma sound prevalent from 1973 on. The original album was a two LP set that could still fit on a standard single CD, but is currently sold as a two CD set. It is available for streaming on the usual sources for anyone wanted to sample this unique music, a music that will retain its excitement, mystery and appeal for centuries to come.

Brian Eno: Another Green World and Discreet Music; Fripp & Eno: Evening Star

In November of 1975, Brian Eno released his third solo studio album, the remarkable Another Green World which, while not as ambient as his upcoming work, is certainly an unconventional pop album full of highly accessible music surrounded with imaginatively unusual context. Eno provides a mix of catchy songs with him on vocals, some amazing guitar work from Robert Fripp, but mostly a level of exotic, quirky arrangements that elevate each and every track. Highly recommend!

In December of 1975, Eno’s fourth studio album is released, Discreet Music, and it is a boldly innovative ambient album. The first side, the title track, is a work of beauty and can be listened to directly or used as effective background music for a range of activities including writing, reading and napping off. The second side is more challenging: three “elastic” arrangements of Pachelbel’s well-known canon where the parts move at different paces — not by chance or performer’s whim but intentionally arranged to distort the relationship of the individual parts and the overall musical experience. One can still hear traces of the original canon — yet each of the three very different arrangements alters the original musical architecture with time-based abstractions that are roughly parallel to distortion concepts in cubism, futurism and surrealism and also seem related to rules-driven processes that are found in works by artists like Paul Klee, Bridget Riley, Sol LeWitt and even those famous rectangle paintings of Piet Mondrian. One also has to give credit to John Cage’s influence which opened up this whole realm of unexpected alterations whether aleatoric or rules-driven.

The most challenging of these three albums, Fripp & Eno’s Evening Star, released also in December of 1975, is another tale of two sides. The first side of four tracks, each with new standard ambient titles, is by far the most accessible and functions very effectively as truly ambient music or even meditative, reflective music, particularly the first, third tracks and fourth tracks “Wind on Water,” “Evensong,” and “Wind on Wind.”

The second side is devoted to a single piece “An Index of Metals” divided up into six tracks. I doubt there are many people that can turn it on in the background and experience a calming or relaxing effect from it. It is filled with tension and not smooth or flowing. I suspect many will just find it plain irritating if using it to relax, read, or write by as it has a somewhat intrusive and ominous character. It is more listening music and needs the attention of an active listener to properly navigate the tension, suspense, and forward progress of the music. The last of the six tracks is the most gritty of all and it ends with the tension decaying as opposed to any resolution. This sets up a nice contrast to some more relaxing ambient music, which would become more and more common and commercially viable thanks to this early work by pioneers like Eno and Fripp.