Genesis: Selling England By the Pound, The Who: Quadrophenia, and much, much more; Fifty Year Friday: October 1973

Genesis: Selling England By the Pound

Released on either September 29, 1973, or more likely October 5, 1973, “Selling England by The Pound” stands as one of the finest progressive rock albums of the 1970s. The sound is superior to that of their previous album, “Foxtrot,” and the music maintains the same level of excellence. It adeptly balances instrumental passages with vocal sections, blending humor (seen in tracks like “The Battle of Epping Forest” and “Aisle of Plenty”) with more serious compositions.

“Firth of Fifth” (note the humor in the title, which is a reference to Firth of Forth , the fjord of the Forth river, in Scotland, north and northwest of Edinburgh) is my favorite track, particularly due to is introductory theme on piano, later reprised by the group, but there is not a single weak moment on the entire album — and quite an album it is, with seven perfectly realized tracks totaling over fifty-eight minutes of magnificent music.

The Who: Quadrophenia

Released on October 19, 1973, this is the Who’s masterpiece about teenage alienation, angst, attitude, and the multiple personalities vying for integration into the evolving identity of an individual. It also addresses the weaknesses within the UK social system and the moments of solace that British youth of the 1960s sought and found in music and by the seaside. Moreover, this work is an astounding musical achievement, characterized by skillful thematic reiteration. Its musical content can be enjoyed both on a visceral level and intellectually, making it enduringly captivating upon repeated listens. Notably, the lyrics were deftly incorporated into music that was apparently written first, and Townshend has delivered exceptionally well-crafted lyrics that serve as the narrative backbone.

Effectively, this is a rock opera set in 1965, centering around a singular British youth, inspired by conversations Pete Townshend had with early fans of The Who. A significant distinction is that, unlike “Tommy,” which featured two songs by John Entwistle, one by Keith Moon, and a reworking of a Sonny Boy Williamson tune, all the original material here is authored by Pete Townshend. The emphasis is on “initial”, since Townshend intentionally provided a framework of lyrics, melody and chords that would develop into final arrangements through Townshend’s working with the band and the studio equipment to achieve the final product. So though Townshend deserves appropriate credit here for the authorship of this impressive work, it is The Who, as a band, that must be recognized for making this an enduring classic.

For those interested in additional information on this great album, please check out this track-by-track review by Caryn Rose written back in 2013 for Quadrophenia‘s 40th anniversary: Track-By-Track Review

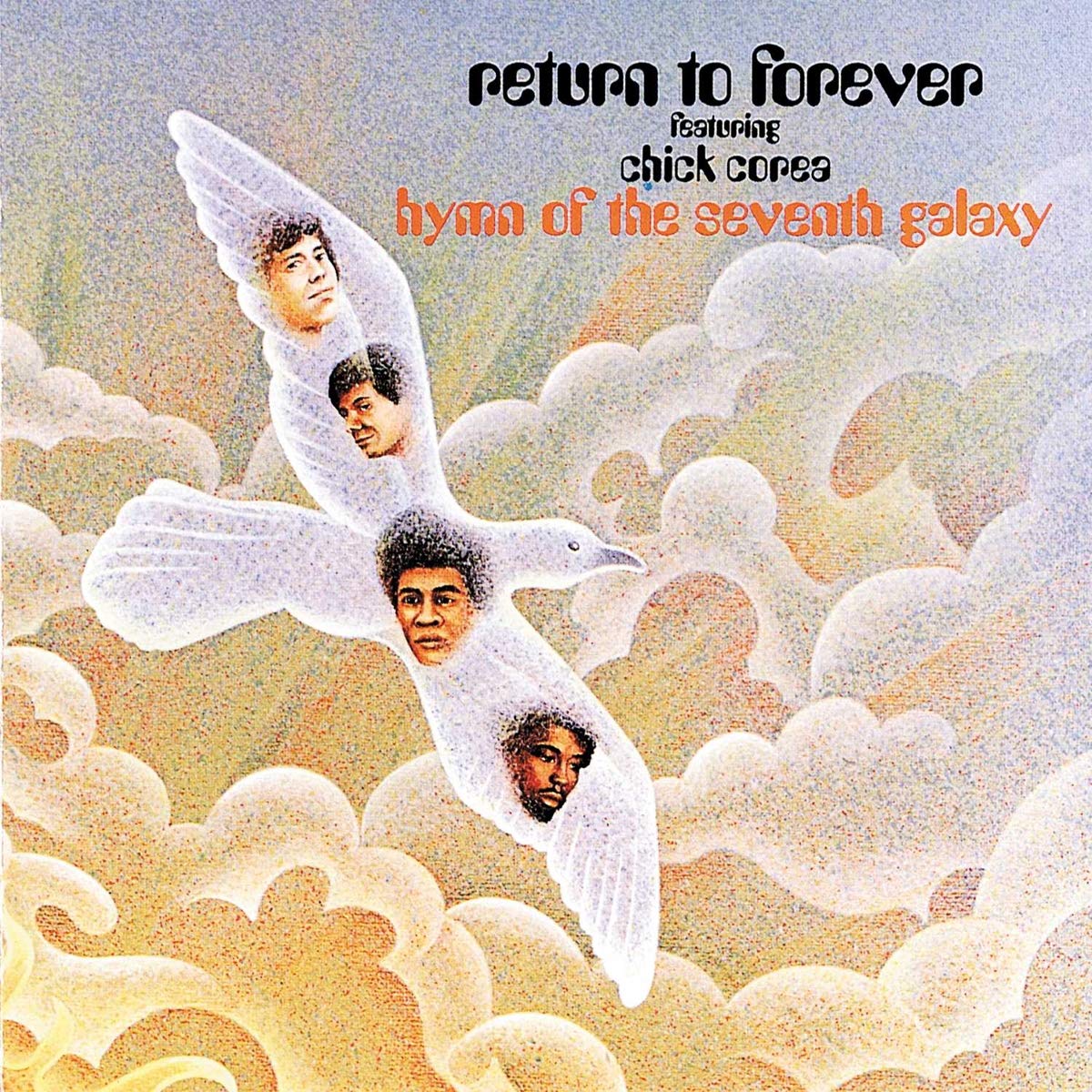

Return to Forever: Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy

Released sometime in October 1973, this third album from Return to Forever magically and masterfully weaves together elements of jazz, fusion and progressive rock. Chick Corea dazzling keyboards and his other worldly — no, make that other galactic — compositions just radiate throughout this album. Fellow band members, Stanley Clarke, Lenny White and Bill Connors are equally up to the challenge, with Mr. Clark providing a wonderfully radiant composition of his own, “After the Cosmic Rain” and exhibiting Olympic-level mastery on electric bass. The coup de grâce is the last track, “The Game Maker”, breathtakingly piloting us over intricate, wondrously, shifting musical landscapes.

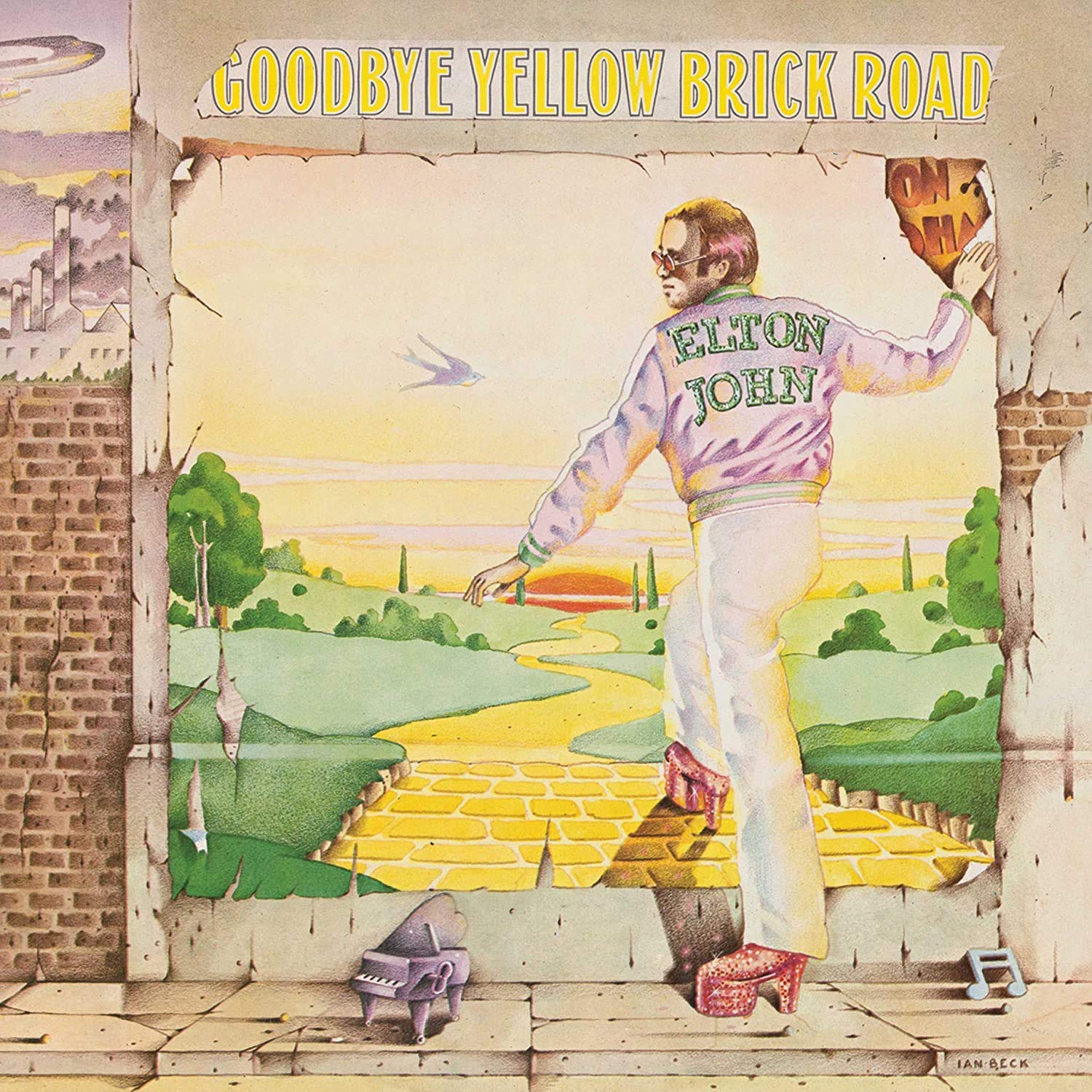

Elton John: Goodbye Yellow Brick Road

The one obstacle that prevented The Who’s Quadrophenia ever getting to the number one album spot in the UK or in the US, was the multi-million-sales avalanche of Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, released on October 5, 1973, almost two weeks before Quadrophenia. Of the slightly over one hundred million copies of albums Elton has sold, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road accounts for over thirty-one million, and continues to sell in substantial quantities to new Elton John fans today.

Rather than compose music and then fit lyrics into the music, Elton John’s method in the 1970’s, like that of many songwriters, was to take already written lyrics, in Elton’s case partnering with Bernie Taupin, and then create music too complement those lyrics. Considering the nature of many of Taupin’s lyrics, it is rather incredible that Elton created so many highly popular and widely-appealing songs from the initial material. Goodbye Yellow Brick Road, in a sense a loose or partial concept album, provides insight into Elton’s range of compositional skills, with the initial track, “Funeral For A Friend:, being one of his rare instrumentals, providing a glimpse into the depth of his creativity when not bound by lyrics. This instrumental introduction is effectively paired with “Love Lies Bleeding” providing an almost progressive-rock opening for the album.

Overall the album is quite good and along with his two albums from 1970 (Elton John and Tumbleweed Connection) and his live album from that period (17-11-70) are a set of his works I hold in high esteem. Now, though the first side and last side of the original 2 LP “GYBR” is indispensable, as is the first track of side two, and the last track of side three, the material in between could be omitted, to get a very fine single LP album, at a total length of around 45 minutes. Now some may wish to further add another track like “The Ballad of Danny Bailey (1909–34)” resulting in an album that still comfortably adheres to standard LP limits. That said, the CD, containing over 76 minutes of the original material, is now sold at roughly the same price as other Elton John albums from the early seventies — so even though a slimmer, arguably better album could be achieved, what’s the point — given how effortless it is to replay favored tracks on a CD or to skip those not currently of interest.

Billy Cobham: Spectrum

Spectrum, Billy Cobham’s first album as a leader, released October, 1, 1973, is as impressive and important as any fusion album of 1973. The combination of Cobham and Jan Hammer dominate the album, and the supporting resources, particularly Tommy Bolin who is present on over half of the musical material, round out this excellent work. Album includes duets between Cobham and Hammer, Hammer soloing on acoustic piano on the beautiful ballad, “To the Woman but it is the longer tracks, and several lengthier tracks including the opening track, “Quadrant 4” full of energy and purpose, “Stratus” with remarkable bass work from Leland Sklar, and the fast-paced, electrically-charged title track, “Spectrum” with Joe Farrell on sax and flute, and Jimmy Owens on trumpet and flugelhorn.

Gryphon: Gryphon

Gryphon’s first album is a unique blend of folk and rock, incorporating both modern elements (guitar, bass, bassoon, trombone, drums) and earlier musical instrumentation (mandolin, recorder, crumhorn) into a successful set of songs. In late 1973, there were several folk rock groups, such as Fairport Convention, Steeleye Span, and Pentangle, but Gryphon, with two of the group members—Brian Gulland and Richard Harvey, both graduates of London’s Royal College of Music—distinguish themselves through a level of originality that transcends replicating traditional Celtic folk harmonies and melodies. Their occasional use of late 19th-century and 20th-century dissonance, not found in traditional English, Irish, Scottish, or Welsh music, coupled with their colorful and sometimes unconventional instrumentation, creates a new sound that effectively captures and maintains the listener’s attention. Later, the group would develop a more progressive-rock sound, but this first album is a fine one, deserving to be enjoyed and appreciated on its own terms.

Renaissance: Ashes are Burning

Renaissance’s fourth album, “Ashes are Burning,” was released on October 10, 1973. The album opens with full intensity, featuring the instrumental introduction of “Can You Understand?” This segues into the introspective acoustic main section, accompanied by some orchestration, showcasing Annie Haslam’s spellbinding vocals. The introductory material returns to conclude the piece. Such artistry and high-quality musical content are defining characteristics of this album, effectively blending classical, folk, and rock elements. The album concludes with the majestically crafted and musically uplifting “Ashes are Burning,” providing an emotionally captivating ending to a highly enjoyable album.

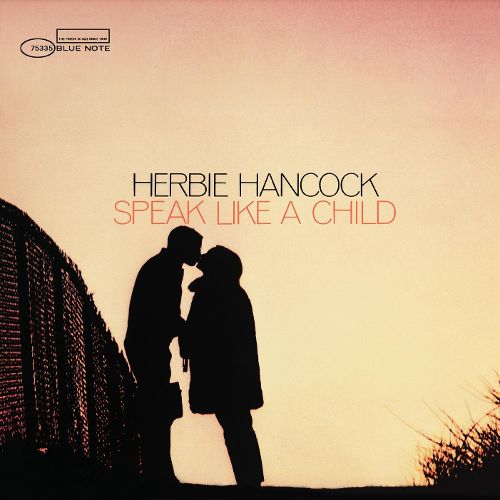

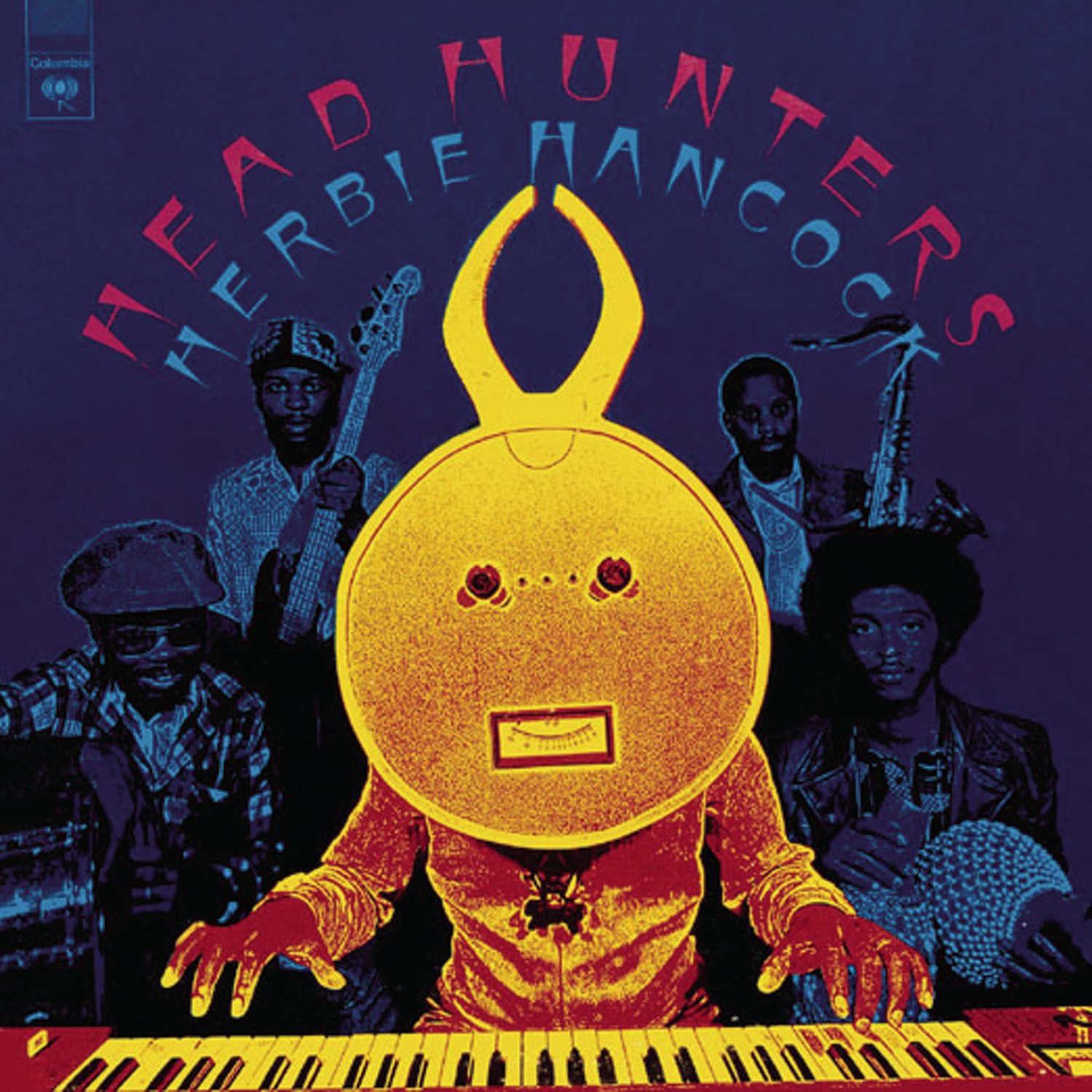

Herbie Hancock: Head Hunters

Released on October 26, 1973, and recorded the previous month, this landmark album signifies a conscious shift in direction for Mr. Hancock. It departs from his previous, more progressive and adventurous modal-based music, embracing a solidly tonal funky style of jazz. For this endeavor, he replaced all the members of his previous sextet except for himself and the talented Bennie Maupin on reeds. Remarkably, this jazz album achieved significant commercial success, foreshadowing George Benson’s stunning commercial breakthrough three years later.

The album starts off with “Chameleon,” featuring its initial foundation of two relentlessly repeated bass figures. However, the music is far from stagnant; it organically develops as it progresses, with the bass occasionally taking a secondary role but always remaining fundamental to the overall forward motion. The improvisation, while solidly jazz-based, aligns with a generally funky mood. Toward the end of “Chameleon,” we encounter sparkling chord changes reminiscent of a chameleon changing its exterior color, yet it retains its essential nature—similar to the music—concluding with a more static, funky ending. This is followed by an abstracted, funky rendition of Hancock’s classic, “Watermelon Man,” creatively presented to sound fresh, innovative, and slightly futuristic.

Side two starts with “Sly,” a vibrant homage to Sly Stone that includes some wild, abandoned, but clearly intricate interplay between Maupin’s sax and Hancock’s keyboards. This dynamic exchange offers all the excitement and vigor of the free jazz of the era, yet within a tonal, structured framework—making it accessible to a wide range of listeners. The album concludes with the reflective jazz tone poem, “Vein Melter,” seemingly representing the impact of heroin. The sense of time is significantly slowed by the floating, detached music, free from earthly worries or concerns. Notice the slow beat that initiates, persists, and concludes the track, possibly symbolizing the futility of the heroin experience. This second side, featuring “Sly” and “Vein Melter,” stands as one of the best single LP sides of any album from the 1970s.

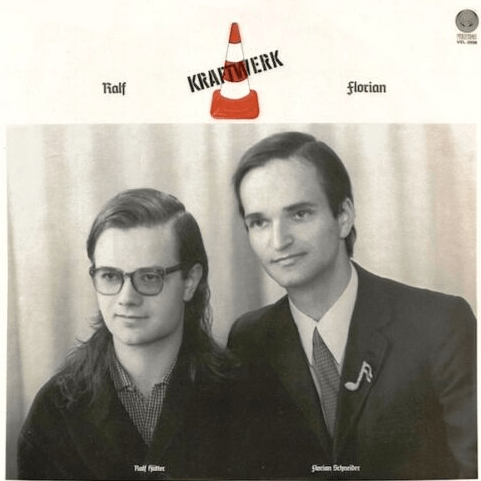

Kraftwerk: Ralf und Florian

Released sometime in October1973, Ralf und Florian is the third studio album by the soon-to-be influential German electronic music pioneers, Kraftwerk. At this time there group is just the two former students of Düsseldorf’s Robert Schumann Conservatorium, Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider The album is influenced heavily by “classical” or conservatory/university ideas about electronic music, but it is clear that a more accessible element is added into their works. This is far from their pop-flavored, and very influential, fourth album, but it still holds a special place in the band’s discography, marking that important transitional phase between their early “experimental” electronic work and the groundbreaking sound they would later be known for. The most intriguing work on the colorfully diverse side one is the pattern-based “Kristallo.” The second side open with “Tanzmusik”, which comes the closest to the music of their next album, with its lighthearted texture, vocoder-enhanced vocals and relentless drive. The album concludes strongly with the longest track, the relatively accessible “Ananas Symphonie” (“Pineapples Symphony”) with the vocoder, this time, used to modulate their voices to sound detached and machine-like. Ironically, though, the piece also creates a relaxing, mediative soundscape reminiscent of a tropical island — pineapples and traces of seashore sounds included.

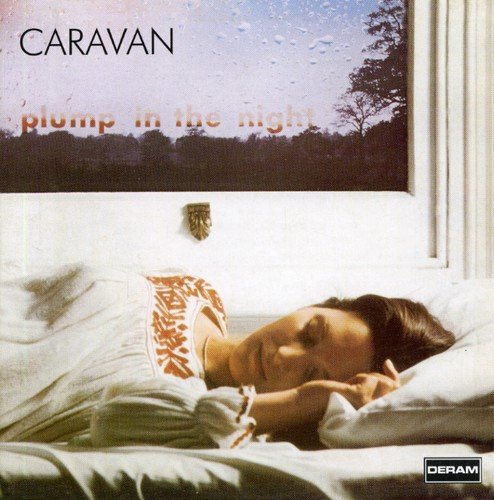

Caravan: For Girls That Grow Plump in the Night; Lou Reed: Berlin

With changes to their lineup, the loss of bassist Richard Sinclair and keyboardist Steve Miller and the addition of Richard’s cousin, Dave Sinclair on keyboards, and Geoff Richardson on viola, Caravan moves away from the more progressive, jazz-infused sound of their previous album, to a less progressive sound infused with some pop elements of the late sixties The highlight of this fifth studio album, released on October 5th, 1973, is the medley on the last track, “L’Auberge Du Sanglier / A Hunting We Shall Go / Pengola / Backwards / A Hunting We Shall Go – Reprise”, which includes strong guitar work from Pye Hastings, impressive electric viola and cello from Richardson and Paul Buckmaster, respectively, some sensitive acoustic piano from Dave Sinclair and a solid orchestral arrangement from John Bell and Martyn Ford.

Also, on October 5, 1973, Lou Reed releases his poignant concept album, Berlin. Though not as melodically memorable as his previous album, and with some musical content from earlier works recycled or redeployed, the album is still deserving of attention. The last track, in particular, provides an affecting and fitting conclusion to the work.