Fifty Year Friday: March 1970

Miles Davis: Bitches Brew

It was sometime around 1971 (and maybe as early as 1970) that I first saw some promotional marketing material for a mail-based membership club called the Seven Arts Society. It wasn’t offering the usual record club membership (where one could buy 10 albums for $1 and then have to buy more albums later), it was a one time $7 fee to a club that sold mostly books on the seven arts (painting, sculpture, architecture, drama, literature, music and photography) as well as small book-shelf friendly reproductions of sculptures. I put it aside and didn’t think about it again, until a received another version of their promotional mailing that included a picture of the stunning cover of Miles Davis’s Bitches’ Brew. At this point, even though I had never knowingly heard a note of Miles Davis, I took the ad very seriously and noticed that for $7 one could get membership into the Seven Arts Society that included a couple of items I wasn’t particularly interested in and two items that did capture my interest: the Miles Davis album and a 10 LP set of classical piano masterpieces. The first thing I did was to get my father’s take on the overall legitimacy of the membership and his personal verification that there were really no strings attached, and though he advised against my signing up, he did so with limited conviction. This step completed, I then had to decide which was the better choice: the Miles Davis two record set or the Piano Masterpiece. I knew nothing about Miles Davis at that time, and wasn’t sure what kind of music I would be getting. On the other hand I was developing a growing love for classical music, and this 10 LP set had one entire LP of Mozart, two LPs of Beethoven, and half a side of Tchaikovsky — composers of which I had recently been buying recordings of their symphonies. I also knew a little bit about the other composers included as I had started casually listening to the local commercial classical AM and FM radio station., KFAC-FM. Ultimately I decided that 10 LPs were much better than 2 and figured I could buy the Miles Davis 2 LP album later.

It turned out the 10 LP set was a smart purchase. The set was in a quality box with the highest quality LPs I had ever seen. Deutsche Grammaphon produced thick, heavy, noiseless LPs. The sound was clearly superior, even on our modest sound system, which had been very recently upgraded from a mono cabinet to a radio shack stereo turntable, amplifier and a pair (a pair!) of speakers. And even to my rather limited sensibilities, it seemed to me the orchestras and pianists were of the highest possible quality. I started by listening to the Mozart and Beethoven, working through the 10 LPs in order, and playing the Beethoven LPs several times before getting to what I considered to be the second tier composers of the fourth LP, Schubert and Schumann, composers I had heard little about and less of their music. I was pleasantly surprised with Schubert’s Marche Militaire and Opus 103 Fantasy and by the delicateness and clarity of the solo piano sound. The music sparkled and sounded so perfect and so, well, pianistic. Next, I was really impacted by the Schumann piece that started on that same side and continued on the second side. A piece with both an English name, “Scenes From Childhood” — and a German name that I couldn’t pronounce, Kinderszenen, but now knew what it meant. That first “scene”, “Of Foreign Lands and Peoples” had one of the most haunting, evocative melodies I have ever heard up to that time — the second theme, even further heightened by its harmonic, rhythmic and thematic relationships to the first, simpler, more innocent theme. That first side of that fourth LP would get played many more times, more than the Beethoven LPs . However, it wouldn’t get played the most of those ten LPs. Soon I came across the famous Chopin A-flat Polonaise (slightly familiar to me from hearing it once on the radio [hadn’t yet realized it was used in the Wizard of Oz] and promising myself that I would one day have a recording of it) on the second side of side six and Prokofiev’s Opus 11 Toccata on the tenth LP both played by Martha Argerich who along with Christoph Eschenbach who was the pianist on the Kinderszenen and Sviatoslav Richter who was the pianist on the Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto became immediate favorites of mine. By the time I had finished that tenth LP, this was my favorite LP set in my modest collection, at least until I spent $20 to buy a 21 LP set of Alfred Brendel performing Beethoven’s piano works.

Now, please note, that I had expected I would purchase the Bitches Brew LPs when I received the catalog from Seven Arts. However, much to my surprise, it was priced at twelve dollars, more expensive than what it would be if I had purchased it at one of the newly-being-built discount mega-record stores. So I told myself that I would purchase it later. But time went on, and it wasn’t until the end of the 1980’s that I purchased my first Miles Davis album, Amandla and it wasn’t a few days ago that I first heard the entire Bitches Brew album from start to end.

And though it is nowhere close to Kinderszenen, Chopin’s famous A-flat Polonaise, the Prokofiev Toccata or even the Ravel Piano Concerto performed also by Martha Argerich (in that 10 LP Great Piano Masterpieces set I am still in love with), Bitches Brew is a very consequential album that makes use of sound and space much like the Miles album before it, In a Silent Way, but has a greater focus on energy, drama and drive than the more ethereal and beautiful In a Silent Way. It combines elements of psychedelic rock with jazz and modern classical improvisation. Along with In a Silent Way, Bitches Brew has had considerable influence on many styles of music in the next few years including rock, funk, jazz and prog-rock.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: A Beard of Stars

At around the same time I purchased the 10 LP Great Piano Masterpieces, my dad had taken my sister and I to one of the newly opened Wherehouse record stores, the first one opened in Orange County, a car drive of about 20 to 25 minutes. Not having much money, I bought a bargain-priced ($4.99) three-LP box of Mozart late symphonies, and some “cut out” records — records reduced in price with a corner cut out, or a small notch cut or small whole punched in the in the outer area of the cover. The records I got were three or four LPs from the Czech Supraphon label of exotic named composers like Jiří Antonín Benda, Vojtěch Matyáš Jírovec, Václav Pichl and Václav Voříšek each priced at $1.99 — and a single cut-out LP priced priced at exactly 99 cents, an album that did well in the UK and so was released in the US on Blue Thumb, but failed to sell and so ended up in the cut-out bin. I had never heard of this two-person band (their name was not one to invoke confidence) and the dreary photo of a single, unknown musician on the front cover and another on the back, was not particularly appealing, but there was something appealing about the title of the album, Beard of Stars, and the track names on the jacket, the first of which was title “Prelude” with the ones following seemingly having a connection to folklore or fantasy with titles like “Pavilions of Sun, “Wind Cheetah” and “Dragon’s Ear.” What sealed the deal was a sticker on the LP indicating that there was also included inside (as a bonus!) their hit single, “Ride a White Swan”, which, like the name of the group, I had never heard of before, and, all things considered, I figured there was no harm in taking a chance at 99 cents — money I could quickly recover working at the school cafeteria before school started and during half of my lunch period each day.

I can’t say how much I was amazed and delighted at all six of the symphonies in the Mozart box set. Also, my sister had bought a two-record set of Puccini’s La Boheme. I had never heard an entire opera before, and how very exciting it was to follow the English translation of the Italian as the plot of the opera unfolded accompanied by a continuous stream of drama-steeped melodies and melodic-like fragments. The Supraphon Czech composer LPs were not as novel as the opera experience, but were quite good in terms of performance and musical content. Then there was the Tyrannosaurus Rex Beard of Stars album, which I had pretty low expectations and much to my surprise was both intriguing and musically satisfying from the opening prelude. There is a level of intimacy throughout each track, and I thought of these two musicians performing in a small venue or someone’s den, crosslegged on the floor. But there is also an intensity, liveliness and forward motion to the album that propels itself through the slower tunes like the simple “Organ Blues” or the dissonant “Wind Cheetah” that ends side one. Side two opens up with more upbeat energy with the title track, of “A Beard of Stars” which effectively serves as an instrumental prelude for side two. It is not until the very end, in the final moments of side two, that the tone and consistency of the album is disrupted with the closing three minutes of the last track inexplicably veering off into an rather unstructured and wild — and seemingly unrelated — electric guitar excursion by Marc Bolan. And though a better and more cohesive ending would be welcome, all in all this is an excellent fantasy-folk rock album filled with a variety of well-crafted and laudably idiosyncratic tunes that make this my favorite T. Rex album.

As mentioned this cut-out version also included a single hurriedly shoved into the interior of the jacket — a single, “Ride A White Swan” that held little interest for me upon first listening and held none of the charm or uniqueness of the album it came with. “Ride A White Swan” produced by Tony Visconti (earlier Tyrannosaurus Rex including Beard of Stars, later T. Rex, David Bowie and the first Gentle Giant album ) was well received in the UK, where it peaked at the number two spot. Though a simple blues-based tune, “Ride A White Swan” is often credited as the first glam-rock song and with its success was the second step towards fame and fortune for Marc Bolan and his new percussionist, Mickey Finn — the first step towards fame being this Beard of Stars album, recorded in 1969 and released March 13, 1970, which, though it didn’t catch on in the U.S. as mentioned earlier, did pretty well in the UK.

Egg: Egg

If Bitches Brew or Beard of Stars aren’t usually classified as progressive rock, even though they should be, Egg’s first album, Egg, released the same day as Beard of Stars, on March 13, 1970, clearly has left the late-sixties genre of psychedelic rock behind, incorporating classical and jazz elements into a rock foundation, but very differently, and less organically, than Bitches Brew. Egg embraces one of the signature elements (excuse the pun since I am indeed referring to odd and sometimes alternating time signatures) of prog-rock to such a degree that the single that preceded the album, their first and only single, starts off with a 4/4 verse with a brief 5/4 part and then with a chorus in 7/8 with the returning verse going from 4/4 to 11/8 — all with matching lyrics that clearly call out what is happening. The first album is equally adventurous with a progressive rock treatment (percussion and bass added à la Keith Emerson’s Nice) of Bach’s famous D minor organ Fugue as well a complete part original, part classical-based symphony taking up the entire second side. Well, almost a complete symphony, as the third movement was dropped by the record execs due to it using material so close to the still-under-copyright “dances of the adolescent girls” section of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and replaced by an alternate, stand alone composition, fitted in at the spot where the third movement was. Fortunately, a test pressing was made and saved that included that third movement which is now available on more recent digital versions of the album. All in all a strong debut by Egg, showcasing Dave Steward on keyboards.

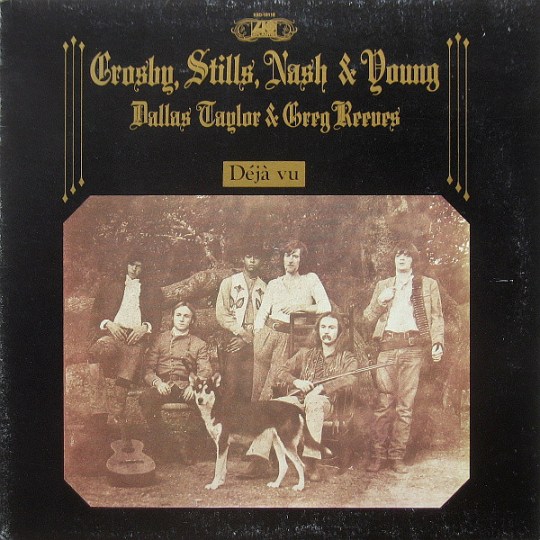

Cosby, Stills, Nash and Young: Déjà Vu

Released on March 11, 1970 Déjà Vu adds Neil Young to the Crosby, Stills and Nash lineup, providing three radio-airplay hits (Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock” and Graham Nash’s “Teach Your Children Well” and “Our House”) as well as Stephen Stills “Carry On” and Neil Young’s “Helpless” and “Country Girl.” If you are looking for a post-Beatles example of what is meant by “Classic Rock”, this album fits the bill as well as any with its strong songwriting, tightly executed harmonies, and brilliant arrangements.

Joni Mitchell: Ladies of the Canyon

This brilliant album, filled with the 20th Century folk-pop equivalent of 19th century art songs, was released on March 2nd 1970. The lyrics range from personal, philosophic, poignant and playful, with the music always of the highest caliber. “Free” is one of many examples from this album of how lyrics and music come together perfectly and includes evocative cello and a brief, illustrative clarinet solo by Paul Horn. By the time I was in college (1973), this was an album that every girlfriend of my close guy friends had in their collection and in the collection of the first young lady I moved in with as well as my close gay friend who always got the best scores on our music theory ear training tests and, then years later, two consecutive English singer-songwriter roommates (one female, one male) when I lived in England. There is just something special about both Joni Mitchell and this album that everyone who has a more sensitive side to them should find intellectually, emotionally and musically appealing.

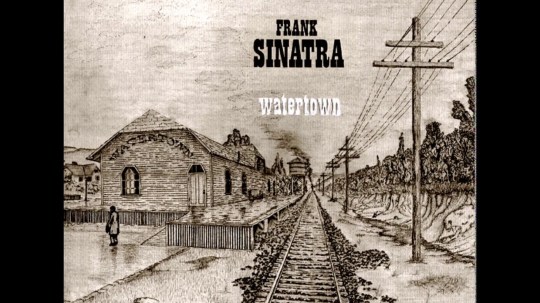

Frank Sinatra: Watertown

One doesn’t usually think of concept albums and Frank Sinatra, but here we have a true concept album of the early 1970s — not a grand prog sci-fi theme, but an real-life concept with appropriate, corresponding songs about a guy whose wife leaves both him and his children. This one tears at your heartstrings and the songs are well written and sung simply and without any bravado. One annoying drawback is that Sinatra is dubbing his voice over the recorded orchestrations — very different than his usual method of operation of recording in real time with the musicians. And although this overdub approach detracts from the album, the album is still worth multiple listenings.

Jimi Hendrix: Band of Gypsies

Whether live or in the studio, it seems that every moment of Jimi Hendrix on tape is priceless! Released on March 25, 1970, this album is still as fresh as when it was recorded on January 1st, 1970. Yes, it’s far from the best Hendrix album or even the best live Hendrix, and Buddy Miles singing (and even some of his drumming) does get in the way at times. But we get some amazing — no, some transcendental — guitar work from Hendrix on the longest track, “Machine Gun”, and side two also has its strengths with renditions of “Power of Soul” and “Message to Love.”

Also worthy of mention is Alice Cooper’s weirdly offbeat, partly Zappa-and-Captain-Beefheart influenced album, Easy Action, Rod Stewart and the Faces’ album First Step, The Temptations Psychedelic Shack, the live Delaney and Bonnie with Friends album, On Tour with Eric Clapton, and Leon Russell’s debut self-titled album, with that classic Leon Russell gem, “A Song For You.’ There is also the live Ginger Baker’s Air Force album that I listened to once when in college and remember little of, but I heartily welcome any comments or reflections about it or any other album from March of 1970.

Which of these many and diverse, distinctive albums of March 1970 do you remember or still listen to (even if only now and then) in the 21st century?

Woodstock: Aug 16-18

Woodstock: Aug 16-18