Fifty Year Friday: Trout Mask Replica, Brave New World

“I don’t know anything about music.” Don Glen Vliet (aka Captain Beefheart)

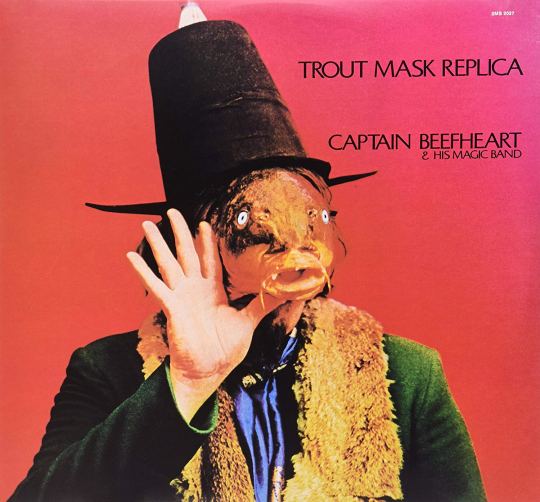

Captain Beefheart & His Magic Band: Trout Mask Replica

Recorded from August 1968 to March 1969 and released on June 16. 1969, Trout Mask Replica is a double album for the ages whether you might love it or hate it — and for most people, it’s rather easy to hate. Far different from Captain Beefheart’s previous album, Safe As Milk (which though partly confined within a traditional blues framework and ethos, provides many imaginative moments and approaches), Trout Mask Replica breaks into territory no artist has yet covered on record: it’s been called out as the musical equivalent of rusty barbwire, and it certainly is as about as far away from easy listening as music gets. But careful, focused, not-so-easy listening reveals the complexity in a large portion of music on the album which includes complex polyrhythms and polytonality.

Yes, there is a lot of non-musical content on the album — Frank Zappa produced this gem and granted total artistic freedom to Captain Beefheart and his band, so one doesn’t get continuous, highly refined music. Instead one gets pockets — and the treasures here are in the instrumental accompaniment and interludes. It’s been said that Captain Beefheart’s voice makes Tom Waits sound like Julie Andrews, that’s true, and the engineering of the album emphasizes these vocals as does their general lack of alignment with the backing instrumentation. It has been alleged that the lack of synchronization was due to Beefheart’s not wanting to wear headphones during recording, which resulted in him becoming hopelessly dependent on his own sense of time and on the immediate sonic reverberations of the studio.

Though there are people that will swear that the main value of this album is to drive away unwanted visitors, its influence on many musicians is indisputable. Bands or individuals reportedly influenced include Henry Cow, The Residents (clearly), The Clash, Tom Waits, The Sex Pistols, Velvet Underground, The Little Feat and myriad others. For me, the repeated polyrhythmic motifs anticipate Gentle Giant, King Crimson and some of the more aggressive math rock bands. If you don’t like this album immediately, try it again, clearing away any possibility of distractions, as well as any expectations, taking the music and non-musical elements for what they are — rejoicing in the unusual, and what most would consider weird, amalgam of musical freedom and musical discipline.

rack listing [from Wikipedia]

All tracks written by Don Van Vliet and arranged by John French.

| Side One | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Title | Length |

| 1. | “Frownland” | 1:41 |

| 2. | “The Dust Blows Forward ‘n the Dust Blows Back” | 1:53 |

| 3. | “Dachau Blues” | 2:21 |

| 4. | “Ella Guru” | 2:26 |

| 5. | “Hair Pie: Bake 1” | 4:58 |

| 6. | “Moonlight on Vermont“ | 3:59 |

| Side Two | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Title | Length |

| 7. | “Pachuco Cadaver” | 4:40 |

| 8. | “Bill’s Corpse” | 1:48 |

| 9. | “Sweet Sweet Bulbs” | 2:21 |

| 10. | “Neon Meate Dream of a Octafish” | 2:25 |

| 11. | “China Pig” | 4:02 |

| 12. | “My Human Gets Me Blues” | 2:46 |

| 13. | “Dali’s Car” | 1:26 |

| Side Three | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Title | Length |

| 14. | “Hair Pie: Bake 2” | 2:23 |

| 15. | “Pena” | 2:33 |

| 16. | “Well” | 2:07 |

| 17. | “When Big Joan Sets Up” | 5:18 |

| 18. | “Fallin’ Ditch” | 2:08 |

| 19. | “Sugar ‘n Spikes” | 2:30 |

| 20. | “Ant Man Bee” | 3:57 |

| Side Four | ||

|---|---|---|

| # | Title | Length |

| 21. | “Orange Claw Hammer” | 3:34 |

| 22. | “Wild Life” | 3:09 |

| 23. | “She’s Too Much for My Mirror” | 1:40 |

| 24. | “Hobo Chang Ba” | 2:02 |

| 25. | “The Blimp (Mousetrapreplica)” | 2:04 |

| 26. | “Steal Softly thru Snow” | 2:18 |

| 27. | “Old Fart at Play” | 1:51 |

| 28. | “Veteran’s Day Poppy” | 4:31 |

| Total length: | 78:51 | |

Personnel

Musicians

- Captain Beefheart (Don Van Vliet) – lead and backing vocals, spoken word, tenor saxophone, soprano saxophone, bass clarinet, musette, simran horn, hunting horn, jingle bells, producer (uncredited), engineer (uncredited)

- Drumbo (John French) – drums, percussion, engineer (uncredited on the original release), arrangement (uncredited)

- Antennae Jimmy Semens (Jeff Cotton) – guitar, “steel appendage guitar” (slide guitar using a metal slide), lead vocals on “Pena” and “The Blimp”, “flesh horn” (vocal with hand cupped over mouth) on “Ella Guru”, speaking voice on “Old Fart at Play”

- Zoot Horn Rollo (Bill Harkleroad) – guitar, “glass finger guitar” (slide guitar using a glass slide), flute on “Hobo Chang Ba”

- Rockette Morton (Mark Boston) – bass guitar, narration on “Dachau Blues” and “Fallin’ Ditch”

- The Mascara Snake (Victor Hayden) – bass clarinet, backing vocals on “Ella Guru”, speaking voice on “Pena”

Additional personnel

- Doug Moon – acoustic guitar on “China Pig”

- Gary “Magic” Marker – bass guitar on “Moonlight on Vermont” and “Veteran’s Day Poppy” (uncredited)

- Roy Estrada – bass guitar on “The Blimp” (uncredited)

- Arthur Tripp III – drums and percussion on “The Blimp” (uncredited)

- Don Preston – piano on “The Blimp” (uncredited)

- Ian Underwood – alto saxophone on “The Blimp” (uncredited/inaudible)

- Bunk Gardner – tenor saxophone on “The Blimp” (uncredited/inaudible)

- Buzz Gardner – trumpet on “The Blimp” (uncredited/inaudible)

- Frank Zappa – speaking voice on “Pena” and “The Blimp” (uncredited); engineer (uncredited); producer

- Richard “Dick” Kunc – speaking voice on “She’s Too Much for My Mirror” (uncredited); engineer

Steve Miller Band: Brave New World

Also released on June 16, Steve Miller and his band’s Brave New World and Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band’s Trout Mask Replica are as far apart musically as composers such as Muzio Clementi and Harry Partch. Brave New World may display less overt, convention-defying courage than Trout Mask Replica, but the musicianship is solid and Steve Miller’s vocals flexibly fit the songs whether those vocals are reassuring and comforting as with the dreamy evocative “Seasons” or appropriately bluesy as on the Hendrix-like “Got Love “Cause You Need It.” Of course, the hit of this album, is “Space Cowboy” which borrows the ostinato-like chromatic blues riff from Lady Madonna, possibly with Paul McCartney’s blessing who jams (under the psuedonym, “Paul Ramon”,) with Steve Miller on another track on this album, “My Dark Hour.”

Track listing [from Wikipedia]

|

Side one |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

# |

Title |

Writer(s) |

Length |

|

1. |

“Brave New World” | Steve Miller |

3:27 |

|

2. |

“Celebration Song” | Miller, Ben Sidran |

2:33 |

|

3. |

“Can’t You Hear Your Daddy’s Heartbeat” | Tim Davis |

2:30 |

|

4. |

“Got Love ‘Cause You Need It” | Miller, Sidran |

2:28 |

|

5. |

“Kow Kow” | Miller |

4:28 |

|

Side two |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

# |

Title |

Writer(s) |

Length |

|

6. |

“Seasons” | Miller, Sidran |

3:50 |

|

7. |

“Space Cowboy” | Miller, Sidran |

4:55 |

|

8. |

“LT’s Midnight Dream” | Lonnie Turner |

2:33 |

|

9. |

“My Dark Hour” | Miller |

3:07 |

| Total length: |

29:52 |

||

Personnel

- Steve Miller – guitar, lead vocals (1, 2, 4–7, 9), harmonica

- Glyn Johns – guitar, backing vocals, percussion

- Lonnie Turner – bass guitar (all but 9), backing vocals, guitar

- Ben Sidran – keyboards

- Tim Davis – drums (all but 9), lead vocals (3, 8)

- Additional personnel

- Nicky Hopkins – piano (5)

- Paul McCartney (as “Paul Ramon”) – drums (9), bass guitar (9), backing vocals (2,9),guitar (9)