Fifty Year Friday: September 1973

Gentle Giant: In a Glass House

With one good debut album and three excellent albums that followed, Gentle Giant released their fifth album in the UK on the 21st of September, 1973. One of the key band members, Phil Shulman, who had provided both lead and backing vocals, sax, and even some trumpet and clarinet, as well as being a significant contributor of the music and lyrics, determined that touring and other hardships were not for him and his family — and so left the band. With his absence, the group forged a slightly new direction into generally a heavier prog-rock sound with Derek Shulman taking on more lead vocals and Kerry Minnear and Ray Shulman making a greater contribution musically. The result was another excellent album, and for many, their best album yet. Unfortunately, Columbia records, which had released Octopus inin the states, didn’t much care for the music and passed on releasing it to the U.S. market. Certainly a bad decision for both Columbia and the band, as the album did relatively well in the UK, and due to its heavier sound and preference for electric instruments over acoustic would have been a more accessible album for the American public. In fact, although not available as an American release, the import of the UK album ended up becoming one of the best selling imports, selling over 150,000 copies despite the difficulties consumers had in obtaining a copy. Ultimately, the music found its way on to an American release in CD format many years later..

The album is a loose concept album more or less covering the fragility of the human psyche with a general progression from the more degraded states (criminal, psychotic) to more common/normal/prevalent states. The metaphor conveyed in the album’s title is that we live in a glass house, fragile and assailable. The music effectively complements the lyrics resulting in the prog-rock equivalent of a 19th century song-cycle — comprising a collection of interconnected songs, six in this instance. Each song delves into a different aspect of our delicate existence, with the implicit analogy being that, to some extent, we reside in a fragile state, much like an occupant in a glass house. The album begins with the shattering, terrifying, possibly panic-inducing sound of breaking glass, that condenses into a repeated loop in 5/4 time, representing a sort of PTSD-burdened recovery that moves forward, obstinately, enduringly, into the vacillating stream of precarious living. The music that follows is uninhibited and infectious — almost celebratory of the flight of the runaway described in “and free is his future”, yet there is no joy, for “all thoughts are scarred” and hopes are “stained with strange regret”; his dreams are dreams that “he cannot get.”

Next we have a passage of that wonderful Gentle Giant “stride” style (see Fifty Year Friday: July 1971 with additional examples mentioned in Fifty Year Friday: December 1972, Fifty Year Friday: April 1972, Fifty Year Friday: November 1970) followed by a sharp, brittle-ish marimba solo and some moog, haunting vocals, another brief dash of moog and the return of the main theme with final lyrics reminding us of the elusiveness of long-dreamed-for, long-desired freedom: “Senses like sharpened sword, guards for the shadow on his tail.”

While the first track, “The Runaway”, nicely covers “imprisonment escaped yet freedom unachieved”, the second track, “An Inmate’s Lullaby” explores further degradation of the human state where the subject, an insane asylum patient, hopelessly and pathologically absorbed in an opaque internal reality doesn’t have awareness of his own imprisonment..

Gentle Giant’s and Minnear’s unique approach to repetition saturates the musical essence that supports the lyrics. The track opens with celeste, vibraphone, and glockenspiel, accompanied by overlapping vocals from Derek and Kerry, as well as more vibraphone and marimba. The music is disjointed and eerie at times, reminiscent of a diseased mind. The mallet and celeste work by Minnear is generally simple but highly effective, supported nicely by Weathers’ appropriately-timed rhythmic interjections.

The third track, “Way of Life,” which is the last on side one, begins as a musical whirlwind — energetic and occasionally more raw and relaxed, but with interjected, repeated, pointillistic musical cells. The second theme contrasts as a beautiful ballad sung by Minnear, evoking reflection and wistfulness. It’s restated at a higher volume instrumentally, followed by a dramatic transitional passage that guides us into a brief reprise of the first theme. This is then succeeded by an organ-dominated reiteration of the second theme, featuring a yearning repeated organ passage that concludes side one, repeating until it gradually fades away.

Side Two opens up with “Experience” which starts out reflecting on the selfishness of youth, music nicely supporting the character’s musings: “Once I was a boy, and innocent to life and my role in it.” This is interspersed with instrumental commentary, repetition-based, and exquisitely layered with multiple instruments. Included is a subtle motific reference (unveiled to the listener by Phil on bass) to the later hard-rock chorus-like section. But before this “chorus” section, we have a new section with organ and discant recorder presenting a new theme, reflecting the view of maturity, “Now I am a man, I realize my unwordly sins pained many lives.” Included in this is multiple reiterations of the bass-line motif until it explodes into the next section, the loud volume hard-rock chorus with Derek on vocals thunderously proclaiming “I’ve mastered inner voices (for?, of?) making any choices.” Next is a short instrumental section, trademark Gentle Giant repetition, with a stretto-like tail, followed by a short reference to earlier material with bass motif intact, and then a repetition of the chorus with additional electric guitar material from Gary Green. Next is a brief reprise of the opening material with a coda based on earlier material, repeated to the close of the track. All in all, this track offers a truly musical experience, featuring multiple musically diverse yet seemingly related sections, and multiple time signatures that seamlessly work together to form a unified whole.

The fifth track of the album, “A Reunion, is the shortest (two minutes, eleven seconds) and most beautiful section of the album with Phil and Kerry providing string accompaniment (Phil on violin, Kerry on cello) accompanied with acoustic guitar. While the lyrics start off as the innocuous and tender, sentimental reflection of the past spurred by a chance meeting of former partners (lovers, business partners, band members, etc.), the relation of this song to the “glass house” concept is soon revealed: “Sharing thoughts and deeds, simple harmony, plans and hopes erased in our maturity. Now, tomorrow’s dreams are now yesterday” — making this beautiful ballad notably bitter-sweet.

The album ends with the title track, a summation, with very dark lyrics, but very upbeat, exciting music. Much that we identify as classic, post-Octopus, Gentle Giant is included here, the compact phrase-based repetition, instrumental interplay and imitation, Derek’s intense, assertive vocals, multiple time signatures, what I call the Gentle Giant “stride-style” (at the 3:03 mark), and overall infectious music that (depending on the listener) results in listener euphoria. This amazing album then ends with a short unlisted track that is a concatenation of short samples of each track.

Like many long-time Gentle Giant fans, I cannot readily answer what my favorite album is; each is distinct, and even the multiple weaker albums that follow the 1975 Free Hand album have some indispensable material. My best reply to any query about my favorite GG album, is to reference my personal list of Must Listen to Music.

Eloy: Inside

Eloy’s second album, Inside, is a bleak and dense offering, a dark blend of intricate musical craftsmanship. The centerpiece instrument is the electric organ, the sole keyboard used throughout the album. The thick textures are unusually mesmerizing without ever risking tediousness or monotony, and over the course of the album, they provide an overarching binding element.

Such is the consistency of the bleakness that even toward the end of the first track, during a section of repeated triad-based arpeggios—a typical prog technique often bringing a sense of elation and energy—this passage remains dimly shaded due to the music’s minor tonal center.

A notable point to mention is that the second track bears a recognizable similarity to the musical style of Jethro Tull’s Aqualung. This similarity led to substantial FM radio airplay, which, in turn, contributed to bolstering the American sales of Inside.

Faust: Faust IV

With their fourth studio album, released on September 21, 1973, Faust delivers an exemplary masterclass in German Progressive Rock. The first track, appropriately titled “Krautrock,” stands out as the highlight of the album, providing a perfect example of the driving, hypnotic style of “Kosmische Musik” that would soon become the signature of groups like Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk. The second track, “The Sad Skinhead” mixes reggae and punk elements to provide appropriate musical support for commentary on the ethical character of the second iteration of the skinhead — not the relatively harmless skinhead of the sixties, but the fascist-leaning, violent skinhead that would gain numbers in the late seventies. The lyrics reflect this shift: “Apart from all the bad times you gave me, I always felt good with you. Going places, smashing faces, what else could we do? What else could we do?

The remainder of the album continues with a diversity of German Progressive Rock substyles. The third track, “Jennifer”, starts off with a portentous bass that soon provides the foundation for lighter, more dreamy music with repetitive lyrics, followed by a storm of electronic effects and then some rag-tag, saloon piano to finish off the first side of the LP. The second side is also adventurous with five diverse compositions including “Just a Second” with its repetitive bass and expressive electric guitar that gives way to a Stockhausen-like “electroacoustic music” second section, “”Giggy Smile” in 13/8. The final track “It’s a Bit of a Pain”, opens up acoustically, and serenely, eventually followed by strategically placed electronic effects providing the appropriate musical irritation.

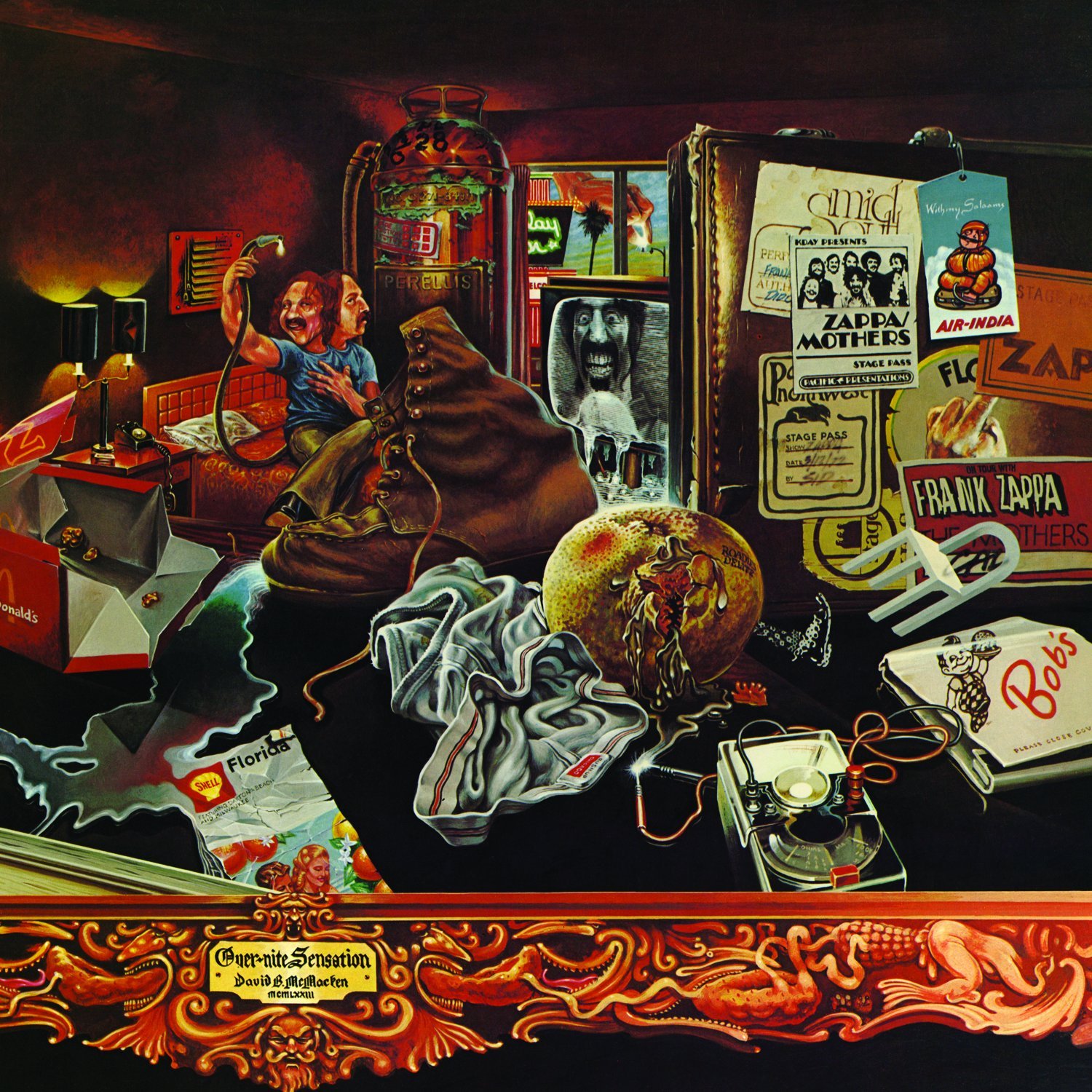

Frank Zappa and the Mothers: Over-Nite Sensation

Released on September 7, 1973, and recorded at the same time as Zappa’s “Apostrophe” solo album, this work artfully brings together rock, progressive rock, jazz-rock, and R&B elements (with uncredited backup vocals provided by Tina Turner and the Ikettes). Though progressive and musically innovative, it is still easily accessible to a wide range of listeners. One may possibly find the often sexually-focused lyrics clever, witty, and sardonic, providing an often detached, dry-humored commentary—or perhaps one will perceive them as waywardly placed in the deeper recesses of the gutter. However, the music itself is generally elevated, showcasing outstanding solo work, including saxophone (Ian Underwood, of course), keyboards (George Duke), and guitar (Zappa), complemented by some excellent mallet work from Ruth Underwood. The music is inherently entertaining, and I believe that it likely had a strong influence on the San Francisco-based Tubes, who began releasing albums in 1975.

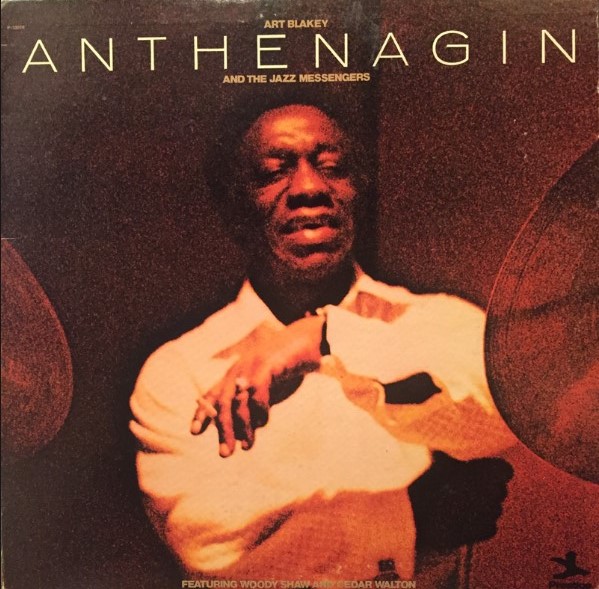

Art Blakey: Anthenagin

Including remaining tracks from the same March 26-29 sessions used for the Buhaina album, Anthenagin is a particularly enjoyable album with Woody Shaw’s brilliant trumpet radiantly shining during his various solos. Cedar Walton is mostly on electric piano except for the introduction of “Without A Song” and for the entirety of Walton’s “Fantasy in D”, the latter being my favorite track on the album. And though my preference would be to have Walton play piano for all the tracks, his electric piano is crucial to the overall impact of another one of his compositions on the album, the title track, “Anthenagin.” This album, sadly, appears to have never been released on CD, but is available on streaming services and on the original Prestige LPs.

Vangelis: Earth

Earth, Vangelis first official solo studio album, stands as a testament to Vangelis’s pioneering spirit and creative prowess, marking his inaugural foray into the realm of official studio albums. Within this musical odyssey, Vangelis reveals not only his compositional finesse but also his remarkable aptitude for arrangement and his astute selection of instruments. While certain moments of the album’s foundational melodic and harmonic material are less than notable , it’s through Vangelis’s virtuosic touch that these seemingly straightforward elements metamorphose into a tapestry of captivating sonic storytelling.

Vangelis’s deliberate curation of instruments becomes a central pillar of the album’s enchantment. His choices encompass a diverse array of sonic colors, each instrument meticulously positioned to weave its own narrative thread. Through this meticulous crafting, the album transcends its individual components, elevating them to become harmonious voices within a grand symphony of sound. Vangelis’s ability to orchestrate these instruments with precision and sensitivity results in a truly immersive experience, where listeners are invited to traverse the intricate landscapes he has diligently designed.

Osanna: Palepoli

Episodic with a few rough edges, Osanna’s 1973 album provides a great immersive listening experience from its relaxed unhurried world-music opening that breaks unabashedly into a passage of celebratory, Italian folk-based dance music until it closes with a mysterious coda based on the opening of Stravinsksy’s The Firebird. This isn’t just Italian Progressive Rock, this is Neapolitan Progressive Rock at its best — uninhibitedly creative and reveling in musical freedom!