Gentle Giant: Free Hand, Renaissance, Klaus Schulze. Harmonia; Fifty Year Friday: July and August 1975

Progressive Rock in the Summer of ’75

The summer of 1975 marks the zenith of progressive rock: the moment when the genre reached its cultural and commercial apex. The journey had been remarkable. The late 1960s and early 1970s saw its birth and evolution, a period of explosive creativity as bands honed their technical abilities and expanded their conceptual ambitions. The artistic potential evident in foundational works like Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and Days of Future Passed was fully realized in a wave of masterpieces, each pushing the boundaries further: In the Court of the Crimson King, Fragile, Thick as a Brick, and Brain Salad Surgery.

By 1975, progressive rock was no longer an exceptional burst of creativity; it had become a normal, even dominant, mode of musical expression. The audience for long-form, complex compositions—accommodating multi-part suites, shifting time signatures, and grand conceptual themes—had been built. The music was not only artistically impressive but commercially triumphant, filling the largest concert halls, arenas, and stadiums across America and Europe.

Yet, this peak was also a turning point. Just as any artistic movement has its heyday followed by phases of sustainment, adaptation and imitation, whether finely-crafted Baroque, emotionally-evocative Impressionism, or intoxicating Swing, so too did progressive rock begin its next chapter. Having reached its summit, the genre moved out of the creative spotlight and began to solidify its place in history, setting the stage for new bands to adapt its sounds and for its original architects to navigate the changing tastes of a global audience.

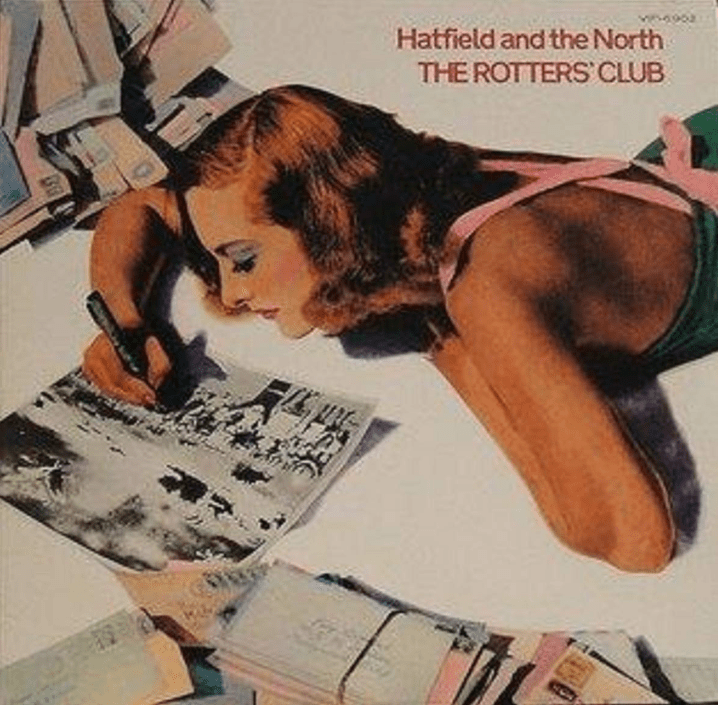

Gentle Giant: Free Hand

Progressive Rock certainly had to be popular for one of the most underpromoted and generally ignored progressive rock groups to have an album climb as high as number 48 on the U.S. Billboard chart. One was still likely to get blank looks when recommending Gentle Giant to friends, but they had made such considerable progress in achieving recognition that they were now more often the main attraction rather than a predominantly supporting act, playing larger and larger venues, getting placed into multi-act festivals and headlining the 7,000-capacity Montreal Forum Concert Bowl and selling out the Centre Municipal des Congrès in Quebec City.

This well-deserved increase in success was crucial, as it helped buffer the band psychologically during a bitter two-year conflict with their UK label, WWA Records. The disputes were numerous and severe: WWA’s US counterpart, Columbia, had refused to release the brilliant but challenging In a Glass House; the band’s management was siphoning off an obscene amount of money; and the label was relentlessly pressuring them to become more commercial and produce a hit single.

After much legal maneuvering (and at what was apparently a significant financial cost), the band finally managed to extricate themselves from their contract. They promptly signed with the more prog-friendly Chrysalis, which had already expressed interest should they become available. This move was not just a business transaction; it was a liberation.

Now on their new label, Gentle Giant could create without constraints. The result was an immediate celebration of this freedom. The first side of their new album, Free Hand, serves as a defiant and musically intricate declaration of independence. Its overarching theme is interwoven with introspective lyrics on a fractured relationship, functioning both as a literal commentary on their breakup with WWA and as commentary on a romantic breakup.

The opening finger-snapping is overlaid with Kerry Minnear’s simple, syncopated piano line, which is quickly joined by Gary Green’s guitar—first with on-beat chords, then with off-beat stabs that accentuate the rhythm. Derek Shulman’s voice enters as another independent line, creating as exhilarating a syncopated opening as has ever been created in rock music.

During the verses, the rhythm section of Ray Shulman on bass and John Weathers on drums lays down a solid six-to-the bar beat. Superimposed over this foundation, the lead vocal and the primary melodic instruments (piano and guitar) operate in a conflicting meter of 7/4. This is not merely a display of technical prowess; it is the lyrical theme made manifest in rhythm. This irrationally persistent dual-meter creates a feeling of daredevil friction — a propulsive yet unsettling groove that is constantly pulling against itself. It musically represents the band’s position: they are intentionally “out of step” with the standard pulse of the industry but are perfectly in sync with their own complex internal logic. The two meters coexist, creating a challenging but ultimately coherent whole — a sonic metaphor for forging one’s own path.

The track ends with a coda carved from the intro, leading directly into the dramatic fugato opening of “On Reflection.” The texture builds with breathtaking complexity: first a single voice, then a second independent voice, then a third, and a fourth. After a short contrasting section, the four-part vocal polyphony is doubled by instruments. The track then shifts to a new, ballad-like theme, delicately supported by recorders, violin, and vibraphone, before the opening fugato returns on instruments alone, trailing off into silence.

The first side culminates with the title track, “Free Hand”, which serves as the narrative and thematic centerpiece. The swaggering, layered opening provides musical continuity, while the lyrics offer a triumphant and unambiguous celebration of autonomy. The aggressive first section is effectively contrasted by a reflective, free-flowing instrumental interlude. Derived from the opening theme, this section alternates between fluid passages and sharp, staccato outbursts. Exciting, climactic transitional material then builds tension before a final recapitulation of the primary theme. A short coda indulges in a few moments of development and ends with a notable cadential flourish — an in-your-face flip of the heels — a musical “so there!”

With “Killing the Time”, side two unexpectedly and amazingly opens up with the sound of Pong — the unassuming, but highly popular video game once found in pizza parlors, pubs, and hotel arcades throughout the U.S., Canada, the U.K., Japan and much of Europe in 1974 and 1975. The brief sound of Pong is followed by musical tone painting at its finest — the music captures idleness effectively with its representation of the seeds of the rhythm searching for a groove and coalescing into what I call Gentle Giant’s stride style (see Fifty Year Friday: July 1971 with additional examples mentioned in Fifty Year Friday: September 1973, Fifty Year Friday: December 1972, Fifty Year Friday: April 1972, Fifty Year Friday: November 1970.)

Functionally, this track extends the album’s concept of new found freedom, portraying the band killing time between concerts. Though primarily minor and minor/modal with its distinctive off-kilter character, once past the opening section, the structural form relies on traditional verse and chorus relationships with a contrasting bridge after the third verse — but with the welcome addition of a sixteen-bar development section after the bridge with a standard repeat of chorus, verse, chorus and fade out. Though the harmony is generally straightforward, using a dominant key and the relative major as contrasting tonal areas, the deployment of chromatic passing chords and controlled dissonance adds to the overall musical interest.

“His Last Voyage” is the most lyrical work on the album, a soft and beautiful Kerry Minnear composition. The form is generally strophic, but constant variation and development provide a sense of passage through tumultuous seas, turning a tragic narrative into a powerful musical metaphor.

This is followed by the penultimate track, “Talybont,” a refreshing neo-Renaissance instrumental that lightens the mood with its cheerful Mixolydian mode and playful counterpoint. Originally composed for a never-released Robin Hood film, its inclusion here provides effective contrast while its melodic contour echoes the album’s opening track, adding to the record’s cohesive feel. It is in rondo form (A B A B A B A) with some musical variation to further increase interest. Interestingly, while the track provides necessary contrast, it also shares the melodic contour of the main theme from “Just the Same.” This subtle connection enhances the album’s sense of unity.

The album ends with “Mobile”, describing life on the road and returning to the album’s general conceptual theme.

“… Moving all around, going everywhere from town to town

All looking the same, changing only in name

Days turn into nights, time is nothing only if it’s right

From where you came, don’t you think it’s a game?

No, no, don’t ask why

Do it as you’re told, you’re the packet, do it as you’re sold…”

The music rocks hard with a solid 4/4 time signature but is enriched with aggressive syncopation, rhythmic displacement, use of synthetic stretto (my term for removing notes in a repeated pattern) for creating momentum and tension, implied metrical shifts (while still in 4/4) and hints of polyrhythm. Add to this effective musical support of the lyrics, and ample musical development, and we have an exhilarating conclusion to one of Gentle Giant’s most unconstrained, most unified albums — an album celebrating, and ultimately documenting, their creative freedom.

Renaissance: Scheherazade and Other Stories

Renaissance’s sixth studio album, Scheherazade and Other Stories, released in July 1975, captures the band operating at the peak of their artistry. Side one starts with John Tout’s piano solo, setting a dramatic tone for the album. Annie Haslam’s ethereal, wide-ranging, and always captivating vocals soar over the first track, “Trip to the Fair,” with its waltz-like foundation reminiscent of a merry-go-round. The 3/4 meter extends into the instrumental middle section, punctuated by snippets of 5/4 that nicely set up the return to the primary theme. This is followed by a short, upbeat, and energetic piece, “The Vultures Fly High,” with its effective modulation in the middle instrumental section. “Ocean Gypsy,” a reflective ballad with subtle musical twists and turns, closes side one.

The highlight of the album is the nearly 25-minute “Song of Scheherazade,” based on the multicultural classic collection of folktales, One Thousand and One Nights. The work is so effectively arranged to incorporate the London Symphony Orchestra that the orchestration seamlessly supports the musical and narrative effort. Annie Haslam is in top form, her voice navigating the epic’s dynamic shifts with grace and power, and John Tout contributes some truly memorable and impressionistic piano interludes that serve as narrative turning points.

Fifty years later, this is an exceptional album to revisit, beautifully showcasing Renaissance’s unique blend of progressive rock and classical influences. This truly effective, enduringly relevant, and genuinely engaging album is one of those artistic excursions that showcase how great music transcends stylistic boundaries to establish its own identity, one ultimately independent of time and genre.

Klaus Schulze: Timewind

Released in August of 1975, Timewind is a turning point for Klaus Schulze, a monolith of sequenced sound that answers the artistic challenge thrown down by Tangerine Dream’s Phaedra. Schulze’s response was to forge his own approach to the analog step sequencer, using its relentless, hypnotic ostinato patterns to create a new musical language that taps into the listener’s subconscious desire for rhythmic order. Time is no longer measured; it is created. This gives Klaus Schulze the freedom to forgo conventional melody, yet provide an accessible, orderly musical landscape: a slow tectonic drift of ambient continents stratified from electronic synthesis.

Even with this new technology, the album demands patience, which in turn allows the listener to fully enter and remain within the two slowly evolving universes that occupy each side of the original LP. This transformation of a mechanical pulse into the catalyst for a new realm of immersive experience now gives talented musicians like Klaus Schulze entirely new architectural tools to build previously undiscovered worlds. For the willing listener, the opportunity is that of complete immersion into the inner dimensions of pioneering soundscapes where time and space are collectively managed by the composer’s creative capabilities and the listener’s personal engagement.

Harmonia: Deluxe

Released in August of 1975, Deluxe, the second album from Harmonia — brimming with sonic colors, warmth and optimism — provides one of the best examples of listener-friendly German “Kosmische Music” (cosmic music). Where some of their contemporaries explored challenging dissonance or more Stockhausen-influenced content, this trio of Neu! guitarist Michael Rother and Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius from Cluster, supplemented by drummer Mani Neumeier from Guru Guru, successfully crafted a sound that was both innovative and accessible, at least to those more adventurous listeners who explored the alternative avenues of music of the 1970s.

The album unfurls a vibrant, welcoming sonic world, seamlessly blending kaleidoscopic electronics with an insistent, forward-driving momentum that immediately engages the listener. The overall architecture relies on rhythms, ostinatos and the artful use of a drum sequencer. This is not consistently pulse-driven, rigid music, but music that appropriately flows, changes course, provides calm and turbulence, and ultimately invigorates with a sense of exploration, motion and scenic excursions.

The synthesizer work is particularly appealing, controlling the tint, brightness and saturation of the passing soundscape so colorfully it becomes visually evocative. The rich, shimmering textures seem to radiate a sonic equivalent of the visual spectrum allowing one to perceive the music in vibrant, shifting hues. With the addition of Rother’s contrasting guitar lines melodically interacting with the multitracked shimmering keyboards, the composite result creates the necessary wonder and interest to give Deluxe its overflowing positive and enduring energy.