Fifty Year Friday: November 1973

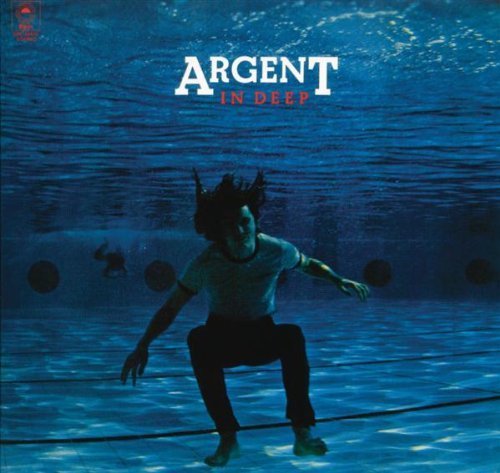

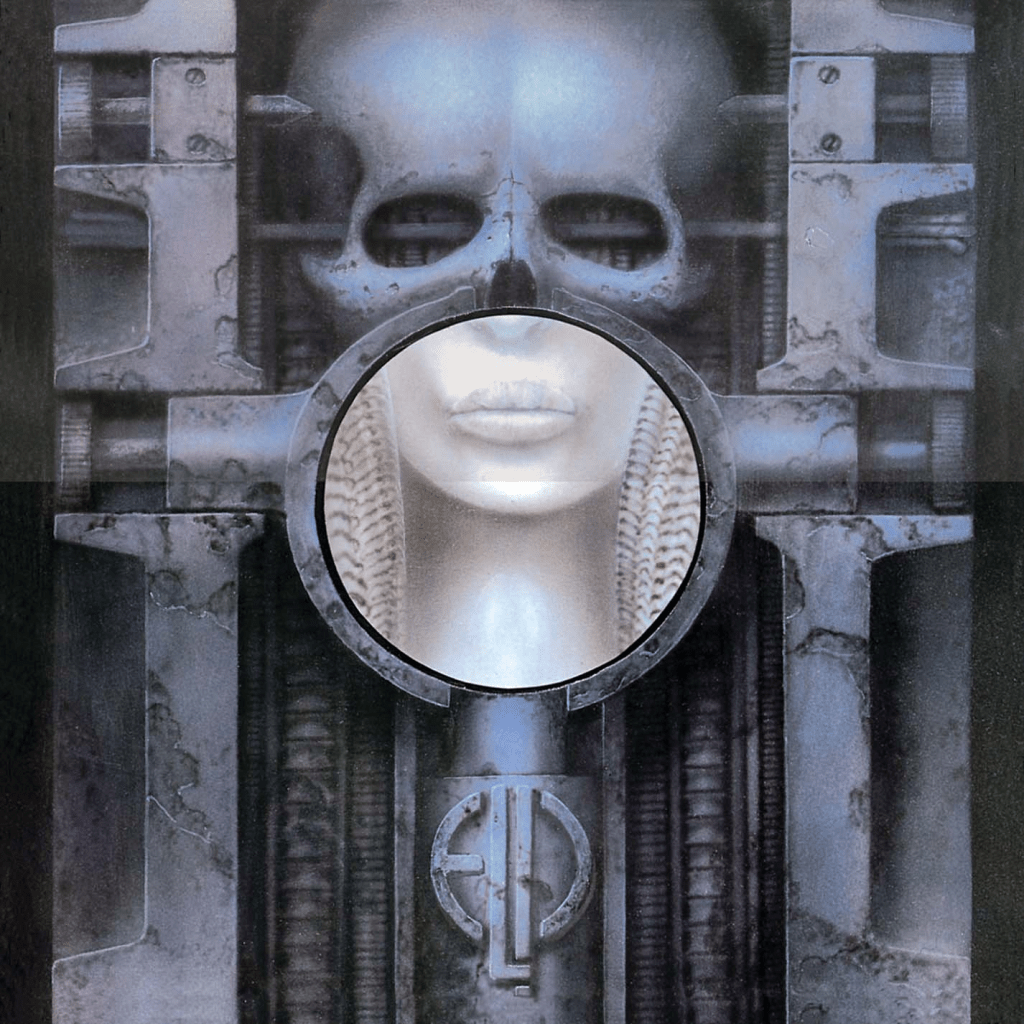

Emerson, Lake and Palmer: Brain Salad Surgery

ELP’s fourth studio album, Brain Salad Surgery, first printing released on November 19, 1973, is the most ambitious of all the ELP albums, and a classic of progressive rock music, providing both moments of dark seriousness, and lighthearted diversion.

ELP’s powerful and dramatic arrangement of Sir Hubert Parry’s “Jerusalem” hymn has a dual function. The first is as an formal opening for the album as a musical event, just as “Jerusalem” might open up a BBC Proms concert at the Royal Albert Hall, or be sung prior to the commencement of the Commonwealth Games or an important soccer match. The second function is to set the musical tone for the album: dense, dark, mysterious, martial and empirical.

This is followed by an amped-up arrangement of the main theme from the presto finale of Alberto Ginastera’s first piano concerto. That arrangement brings out the most thunderous and relentless aspects of the original work. The middle section of original material features an extended drum solo from Carl Palmer on both traditional percussion and a set of percussion synthesizers, which along with additional material provided by Emerson provides a ingeniously compatible “B” section for the piece with the original theme returning to appropriately conclude the work. Worth referencing here is a passage about this track from Mark Powell’s accompanying booklet in the 2008 Sanctuary Records release of the CD:

Soon after the adaptation (of Ginastera’s music) was committed to tape in September, the group became aware that they did not have the rights to release this music. Emerson contacted Ginastera’s publishers who responded that the composer would not allow any adaptation of his works, but they advised him to talk to him personally. So Emerson flew to Geneva to discuss the issue with Ginastera himself. Once Ginastera heard the new arrangement, he gave the authorization to use his piece. To quote Emerson: “He played our recording of “Toccata” on a tape recorder. After a few bars he stopped the tape … and exclaimed ‘Diabolic!’ I thought he said ‘diabolical’ and expected him to show us the door. He had been listening to the tape in mono and our recording was in stereo. I jumped up and switched the machine to stereo hoping he would listen again. It transpired that he wasn’t concerned about that at all. He listened again and declared ‘Terrible!’ which actually was a compliment. ‘You’ve captured the essence of my music like no one else has before’, the great maestro said.”

Greg Lake’s intimately delicate “Still… You Turn Me On” followed by the wildly humorous “Benny the Bouncer” with lyrics provided by Pete Sinfield (lyricist for that legendary first King Crimson album.) provides a sharp relief to the rest of the album and prepares the listener for the musical onslaught to follow. Notable is Emerson’s barroom piano style that adds further lightheartedness and musical interest to “Benny the Bouncer.”

Now the entryway has been opened to the main event: Karn Evil 9 — the title bringing to mind an evil carnival Karn Evil 9 is composed of three sections — the first, second and third “impression” — each symphonic in nature, and though each having its own thematic material, convincingly coalescing into one of the most impressive works in the progressive rock literature.

Karn Evil 9: First Impression brims over with a wealth of music material and alternates vocal sections with remarkable instrumental diversions. There are few if any cases in progressive rock where repeated material holds up so effectively, and part of this is because the group has advantageously leveraged the classical-music theme and variations concept so that verses have varied instrumental support, and part of it is just due to the strength and infectiousness of the thematic material.

The second impression is mostly in acoustic piano trio format, including further display of synthesized percussion nicely support by Emerson on piano and a brief suspenseful middle section that then explodes into unbridled energy with Emerson’s keyboard skills fully on display. Of course, Palmer’s precision percussion work contributes to overall excitement.

The third impression opens with synthesizer fanfare, and the music, in march time, has clear militaristic overtones. Sinfield has again provided lyrics and the sci-fi content is even more topical today with the advanced made in Artificial Intelligence. The unrestrained delivery of the lyrics by Lake, the military Moog fanfares from Emerson, and the relentless percussion contributions from Palmer all over the inexhaustible 2/4 march meter propels us forward into a epic-level instrumental section. The vocals return for the climatic finale with its dramatic end. As a final exclamation point, we get an accelerating, synthesized looped-motif that, on a properly set up audio system, images death-spirals around one’s head.

Back in the last few weeks of 1973, and in the two live concerts I attended in 1974, I found this music exhilarating, impressive, immersive, and magnificent. The same holds today, fifty years later, with the passage of time providing one important alteration to such a summation — the music is also timeless.

Greenslade: Bedside Manners are Extra

Greenslade’s second album, though not particularly cohesive as a whole, contains much to engage and nourish the listener. Underrated, both as a group and as individuals, the level of musicianship here is worth remarking on. Dave Greenslade is an accomplished keyboardist and as a composer would later be in high demand for his knack at writing short instrumentals appropriate as themes for television shows. Doug Larson had a unique, emotionally impactful vocal style, a gift at writing subtly ironic lyrics, and excellent keyboard skills, particularly with electronic synthesizers (he plays the Arp 2600 in the memorable Star Wars Tatooine cantina scene.) Tony Reeves had a jazz background and provided unusually interesting bass work with the group. Andrew McCulloch, played on King Crimson’s second album, and was notably referred to in The Guardian as being one of the most skillful and inventive drummers working anywhere in the jazz or rock spectrum.

The album contains three instrumental pieces, all good, but the highlight are the three vocal works, all of which address the subject in the second person. The title track, is a wistful farewell to the narrator’s current love who will soon be separated from him by being sent off to a distant school, with a particularly poignant ending. The other two songs has the singer intimately yet critically addressing the subject with enough of a cynical tone so that the commentary reflects negatively on the character of the speaker, himself, adding a dimension of irony. The music ably supports the qualities of the lyrics, with notable instrumental passages, making these three vocal works particularly memorable.

Le Orme: Felona e Sorona

Le Orme’s fourth studio release serves as a textbook example of Italian symphonic prog-rock. The album takes the form of a concept album revolving around two interdependent neighboring planets: Felona, a prosperous and idyllic world, and Sorona, a blighted and hopeless realm in decline. The interconnected destinies of these planets become evident near the album’s conclusion when attention shifts to the restoration of Sorona, yielding unforeseen and seemingly unavoidable consequences for the state of Felona.

This allegory of the risks of shifting the focus and care of one undertaking to another and the consequences of such a shift is musically narrated in the band’s native language, Italian, perfect for the associated music created for this concept album. As non-English lyrics were a commercial hurdle for European bands, effectively limiting exposure in American and European markets, an English language version of the album, authored by Van Der Graaf Generator’s Peter Hammill was recorded and released by 1974. The new version, though nicely done, has the drawback of altering the details of the original story, though still true to the allegorical message. More importantly, the use of English-language lyrics, does not provide the same musical compatibility with the original material as Italian. Think La Bohème in English or the English version of PFM’s “É Festa” — just not a good match.

The album sound is pretty good for 1973 — the overall production quality enhances the sonic depth, allowing each instrument to properly contribute to the overall soundscape. Though this trio’s makeup of keyboard extraordinaire (Tony Pagliuca), bassist/guitarist responsible for vocals (Aldo Tagliapietra) and skilled percussionist (Michi Dei Rossi) matches that of the German prog-rock group Triumvirat and the better known Emerson, Lake and Palmer, the music is quite different. Yes, the musical arrangements are intricate, there is the artful and judicious deployment of multiple time signatures, and the musical diversity is remarkable, yet the overall sound is more symphonic with less of the trio-based intimacy of the other two groups. The work is polished, logical, and above all, a joy to listen to, rivaling other prog rock music of its time.

Roxy Music: Stranded

Roxy Music’s “Stranded” is a tasteful testament to the band’s art rock ingenuity, offering a lush and immersive experience that adroitly exposes layers of accessible melodic and harmonic material, a range of rhythmic content, a spectrum of suave musical sophistication and even a touch of avant-garde sensibilities. Released sometime in November 1973, this album marks a pivotal shift in the band’s sound with the inclusion of Eddie Jobson, whose contributions add an additional sonic dimension to the overall effort. Historically, this is an important album with influences on later glam, new wave, synth-pop, alternative and indie rock, as well as (even in Brian Eno’s absence) ambient and electronic pop music.

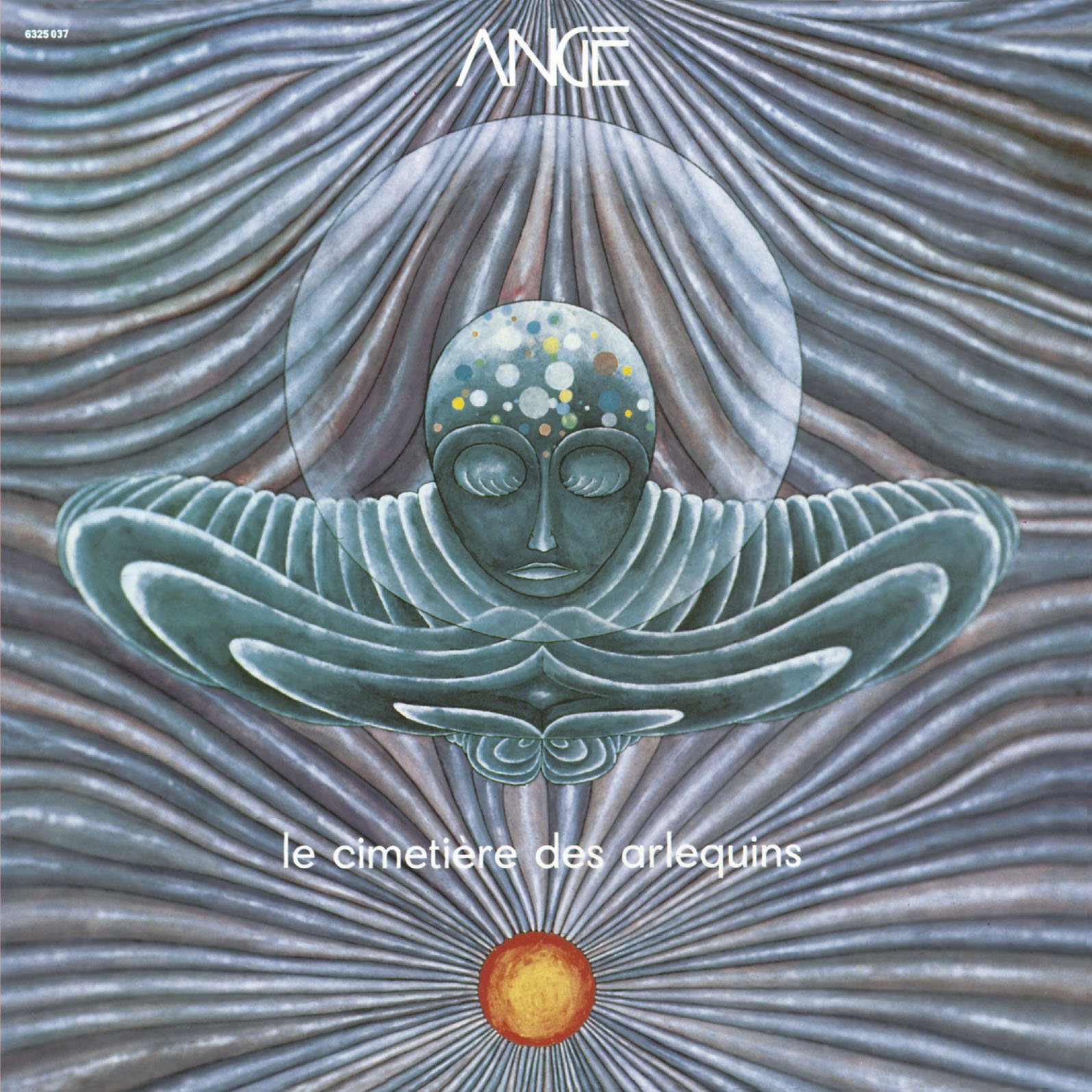

Ange: Le Cimetière Des Arlequins

Ange’s second album, though not as varied and musically complex as their first, has a greater sense of cohesiveness and unity. The lyrics are exceedingly challenging for non-French speakers, but the music is readily accessible and provides an overall musical continuity and art rock sensibility, similar to Roxy Music’s Stranded, even though the styles are very different.

Keith Jarrett: Solo Concerts Bremen/Lausanne

I purchased this three LP set, released in November 1973 at the end of December using some of the Christmas money I had received. I eagerly looked forward to listening to over a couple of hours worth of solo piano. However, there was significant surface noise on the LPs which was particularly audible for solo piano, particularly as the overall sound level on the recording was lower than optimal and there we many quiet passages. I also found it annoying that one of the Bremen pieces was split across sides, and that both the Lausanne pieces were split up.

Fortunately, the CD version of this solves both these issues. The recording still requires setting the volume a bit higher than usual, but there is no disadvantage to this as there is no corresponding surface noise. More importantly one can listen to the improvised pieces as intended and follow the entire flow of the music without interruption — which is a key requirement for this music which beautifully unfolds and evolves, Jarrett being a master musical story-teller.

Throughout the album, Jarrett’s improvisational prowess is on full display. Covering a wide range of emotions and styles, he effortlessly weaves together motifs, melodic fragments, and harmonic progressions, creating intricate and layered compositions on the spot. The way he navigates the keyboard, often employing extended techniques and innovative rhythmic patterns, showcases his mastery of the instrument and his willingness to push its boundaries. His technical skills are incredible, and its a marvel to hear the perfect execution of left-hand ostinatos providing an unfailing foundation for the unbridled excursions for the right hand. The Lausanne improvisations are particularly exciting: Part 1 is a whirlwind of musical innovation, while Part 2 masterfully blends an array of styles and techniques including tapping and knocking against the piano’s wooden exterior with plucking of strings, occasionally punctuated by pressed keys, as well as traditional keyboard performance ranging from a tumultuous free-jazz passage to a number of introspective harmonically-based musings.

Black Sabbath: Sabbath Bloody Sabbath

Black Sabbath’s fifth studio album, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, is a successful expansion of the band’s musical and technical perimeters, We still have the trademark sinister-sounding ostinato patterns throughout the album, but the band has taken a distinctly progressive turn more with more complex song structures, greater musical variety, effective use of synthesizers, and incorporation of other prog-rock elements including strings on the final track and the participation of Rick Wakeman on piano on the fourth and sixth track.

Santana: Welcome

Santana’s fourth studio album, released on November 9, 1973 marked a continuation of Santana’s fusion of rock, Latin, and jazz influences, while also masterfully exploring additional progressive musical elements. Interestingly, the album as also more accessible and more melodic than their previous efforts.

The album begins with Alice Coltane’s evocative and imaginative arrangement of the “Going Home” theme of the Largo of Dvorak’s New World Symphony. The album is consistently excellent and varied, with Flora Purim on vocals for the gravity-defying “Yours is the Light”, the multi-faceted and percussion-dominated “Mother Africa”, and the final track, an effervescent recasting of John Coltrane’s “Welcome” with Alice Coltrane on piano.