Fifty Year Friday: March 1975

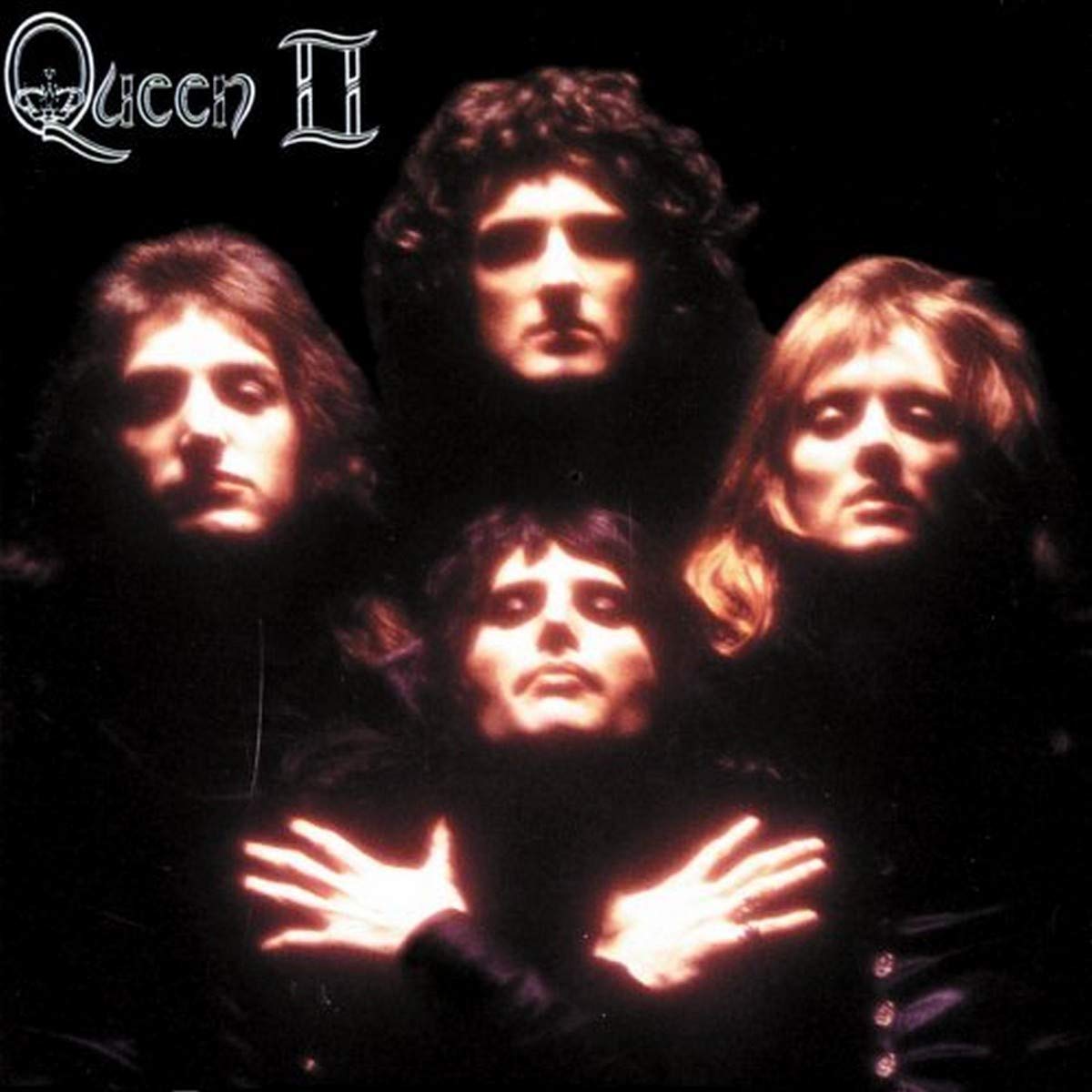

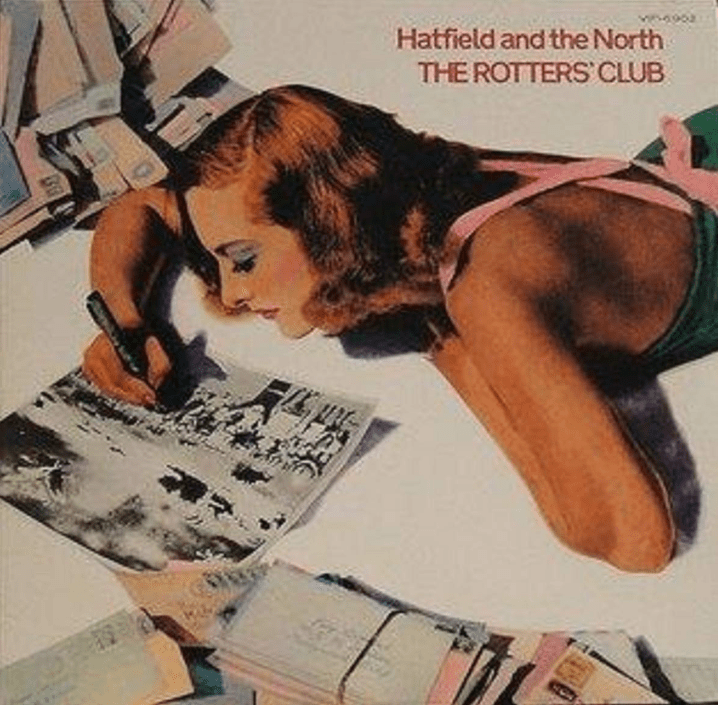

Hatfield and the North: The Rotter’s Club

Released on 7 March 1975, The Rotter’s Club is one of the finest progressive rock albums , delivering a rich blend of humor, virtuosity, and intricate composition that captures the essence of the era while being identifiably distinct from any other album of its time. As the second studio album by British avant-garde and progressive rock band Hatfield and the North, it succeeded their self-titled debut (1973), which established them as a prominent figure in the Canterbury scene. But The Rotter’s Club marked a progression, both musically and conceptually, toward an even more refined and ambitious sound. It is a record that not only brings together various aspects of jazz, rock, and classical music but also emphasizes the playful and eccentric side of progressive rock, a nice contrast to the overly serious, often over-reaching and sometimes pretentious reputation ascribed to it by is staunchest critics.

Tangerine Dream: Rubycon

With the release of Rubycon on March 21, 1975, Tangerine Dream delivered their fourth studio album, a fully realized version of their relentlessly driving “Krautrock” industrial, high-tech, space music. While Rubycon clearly evolves from their previous album, Phaedra, it represents a leap forward, much like the internet is to the stone tablet. Whether Tangerine Dream’s change in direction was influenced by considerations about what musical characteristics would work best for film soundtracks and greater audience engagement, or whether it was partly inspired by the success of Kraftwerk, Rubycon marks the undeniable establishment of a new genre of music — one distinct from anything that came before it. Tangerine Dream’s flirtations with Stockhausen and other electronic composers led them in a direction that was as different from the contemporary world of so-called “classical” and “serious” music as that music was from the tonally extended late Romantic music. What emerged was something accessible, mesmerizing, hypnotic, and directly relevant — an exciting departure from the avant-garde style that, for most of the listening public, had become irrelevant.

Rick Wakeman: Myths & Legends Of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table

Rick Wakeman’s King Arthur, released March 27, 1975, is filled with interesting keyboard and instrumental passages that should interest most progressive rock fans. Though the vocal sections are not exactly comprised of tunes your likely to sing on your own or even along with — they functionally provide narrative, much like Baroque and Classical Era recitatives and, overall the album works well as a dramatic experience. An alternative to the original, with much better overall sound and additional musical content (which had to be left off the original single LP due to time constraints) is the 2012 two-CD version. If you haven’t hear either, best to go for the updated version with the extra material and superior production.

Soft Machine: Bundles

Released in March 1975, Soft Machine’s Bundles is successfully melds an electronic jazz-rock sound with compatible prog-rock elements. The addition of guitarist Allan Holdsworth. known for his fluid, virtuosic playing, injects the album with a fresh intensity, particularly notable in the multi-track Hazard Profile, a nineteen minute five-part suite that showcases Soft Machine’s new direction inclusive of Holdsworth’s soaring guitar work supported by a propulsive, energetic rhythm section. Side one concludes with Holdsworth’s acoustic and beautifully introspective “Gone Sailing.”

Side two is equally compelling with the first four tracks seamlessly blending into a a single experience. The next track, “Four Gongs Two Drums” provides a short percussive intermission, with hints of Indonesian Gamelan followed by the final track, “The Floating World”, a reflective, drifting, neo-Impressionistic composition that gently glides the listener through a bliss-invoking, peaceful and relaxing musical state, providing a fittingly tranquil, dreamlike-end to this excellent album.

Steely Dan: Katy Lied

Donald Fagan and Walter Becker follow up the classic Pretzel Logic album, with another strong album, rich with jazz-flavored chords, Katy Lied, released in March of 1975. Though not strictly a concept album, the album sounds musically unified and could be considered a song cycle of sorts, justifying the term “lied”, a German term applied to art songs, giving us an additional meaning underneath the mysterious reference to the “Katy tried” and “Katy lies” lyrics in the fifth and final track on the first side, “Dr. Wu.”

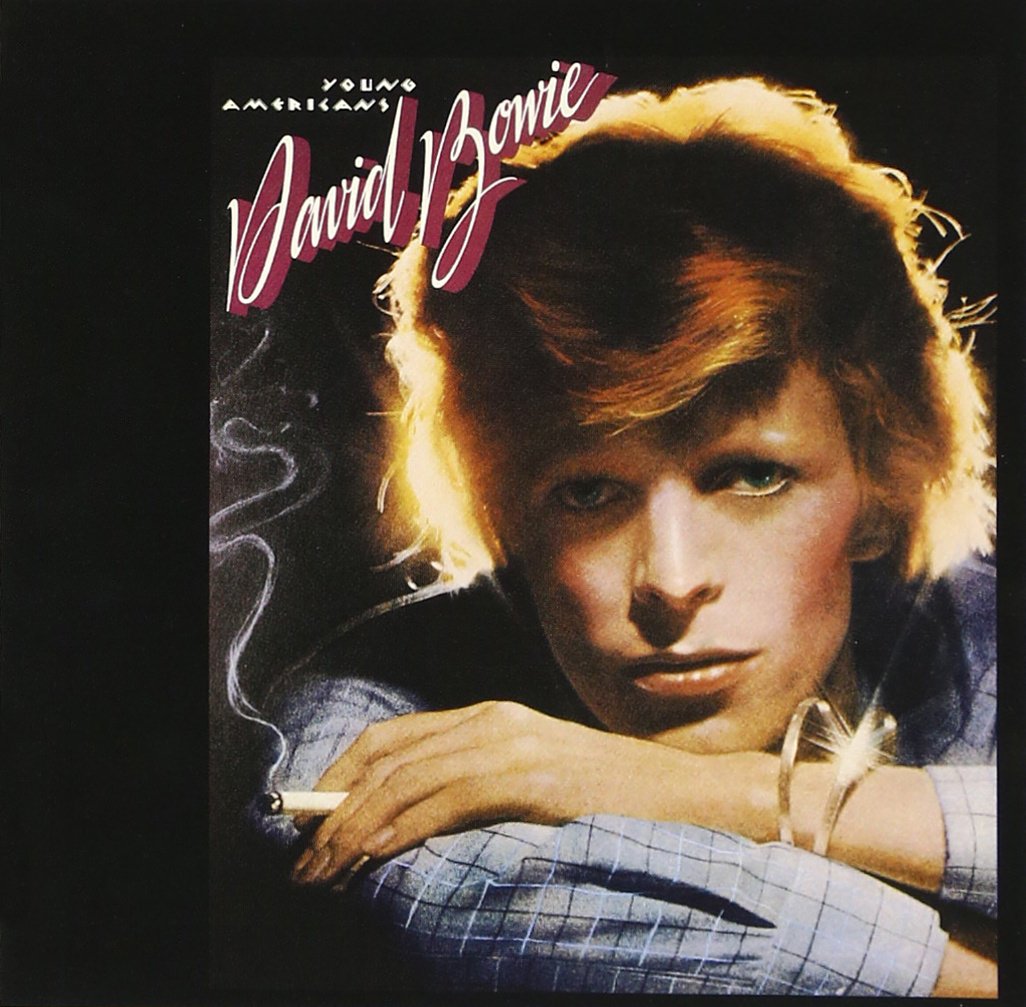

David Bowie: Young Americans

With his ninth studio album, released March 7, 1975, once again, Bowie takes off in another musical direction, extending the elements of soulfulness found in Diamond Dogs and in “Lady Grinning Soul” from the earlier Aladdin Sane, into an all-out exploratory, high-art treatment of American soul music. The arrangements are sophisticated, with Tony Visconti deserving similar praise as Bowie for his musical versatility and with strong contributions from Carlos Alomar and additional input from a twenty-three year-old Luthor Vandross. The strongest track, “Fame,” was initially based on an Alomar guitar riff, with John Lennon, who was visiting the New York Electric Ladyland studios, assisting David Bowie in the authoring of the song by providing his sarcastic, ironic, and pessimistic take on the vagaries of fame.