Fifty Year Friday: May 1975

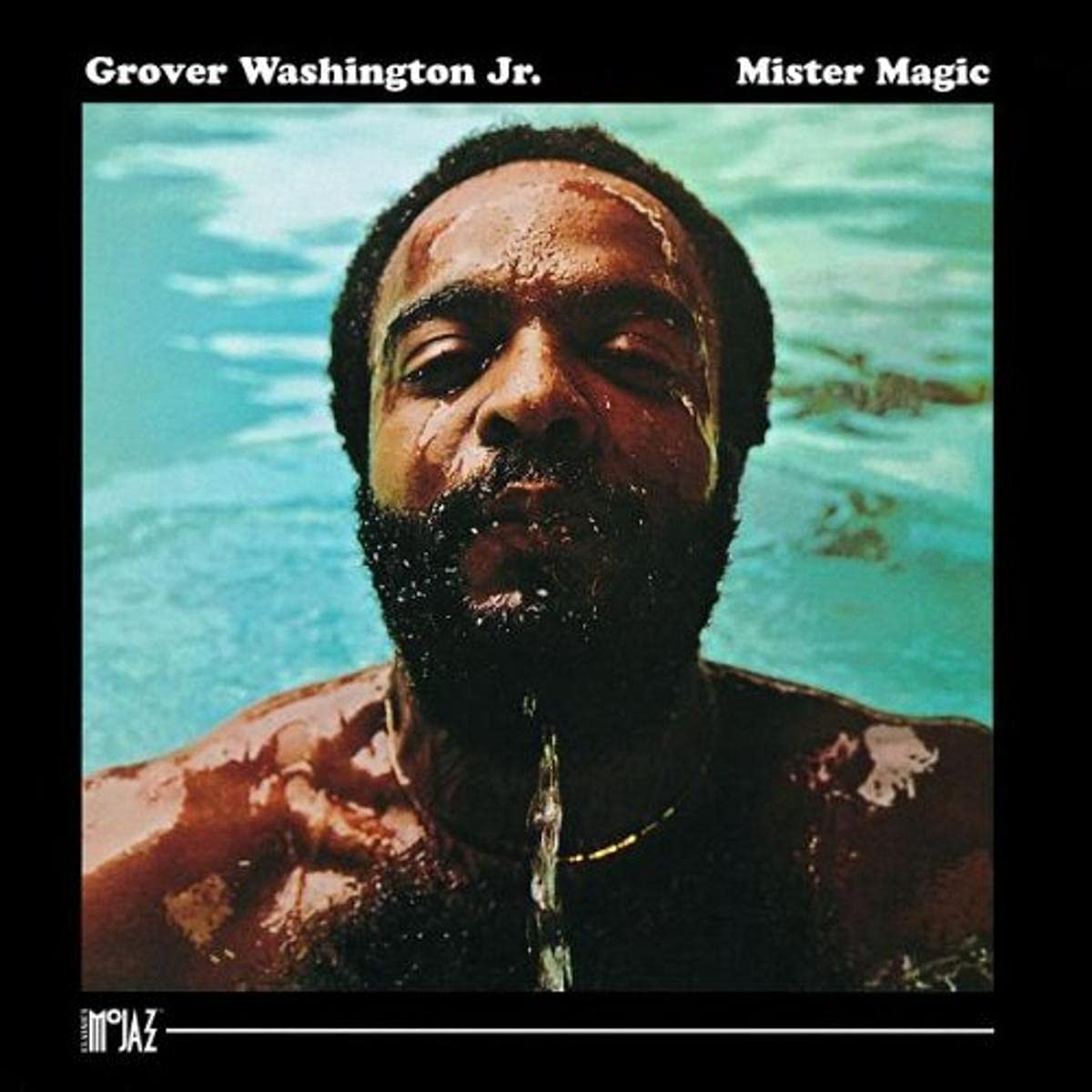

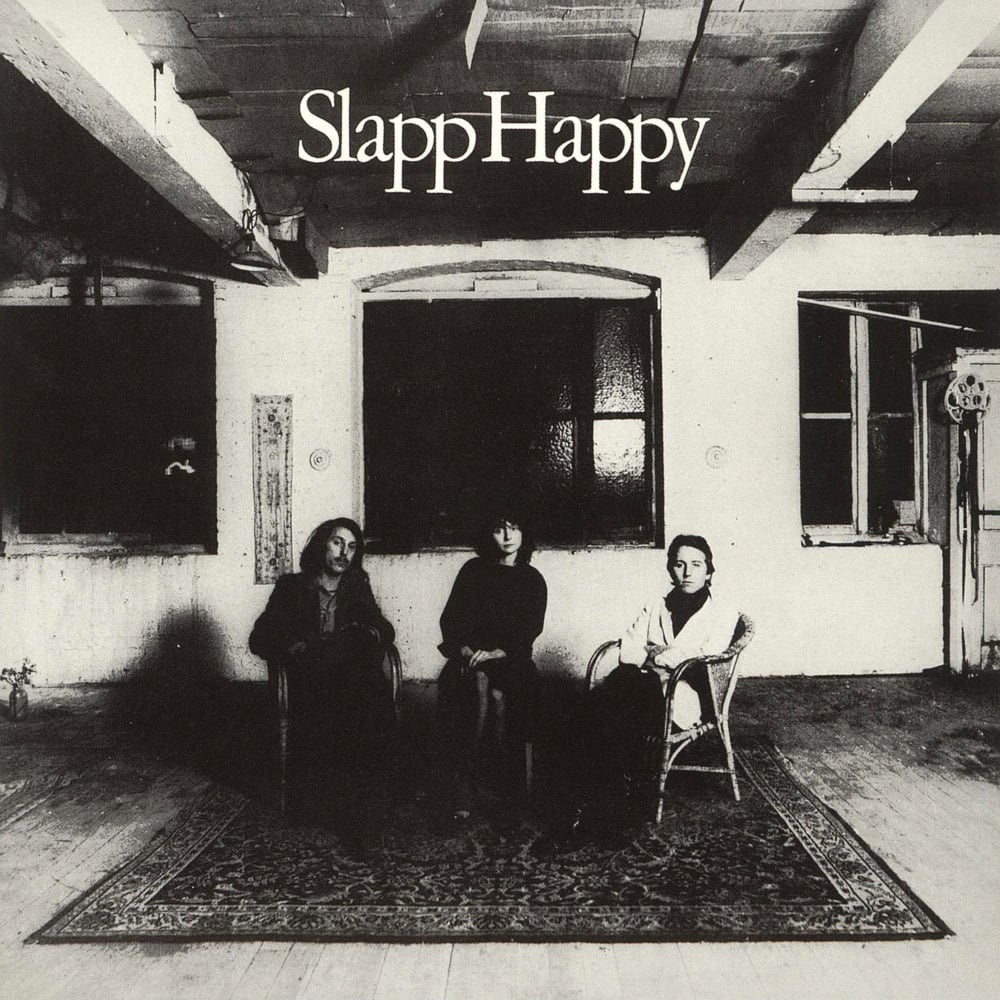

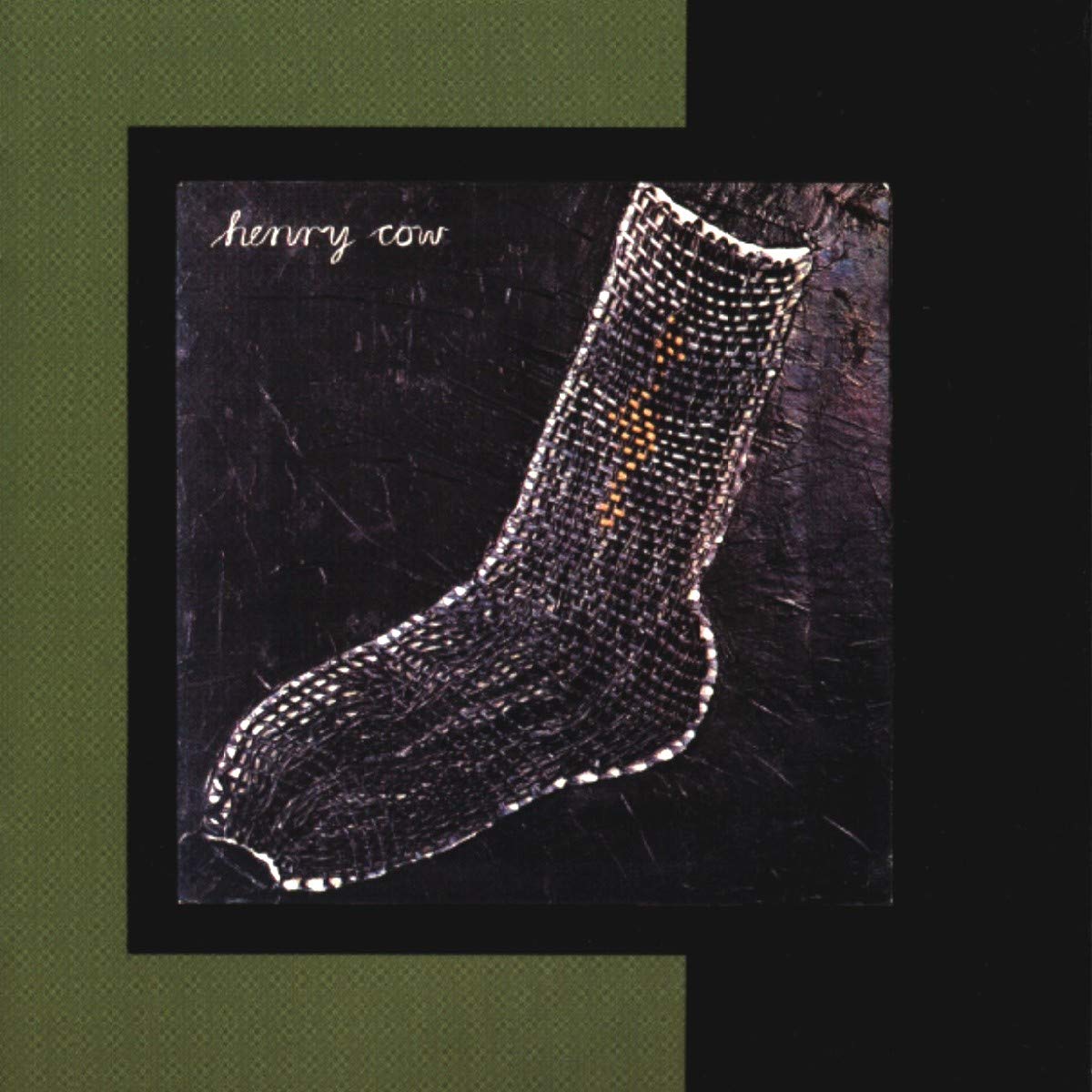

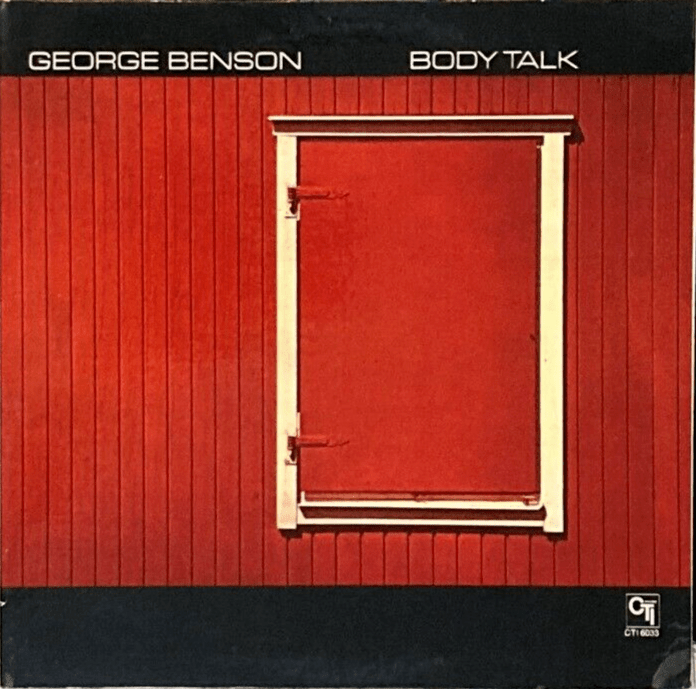

Henry Cow: In Praise of Learning

Henry Cow released their second album featuring members of Slapp Happy on May 9, 1975. Fiercely uncompromising, both musically and ideologically, it seamlessly blends rock, Twentieth century classical composition, and radical political commentary with a precision, ambition, and effectiveness as praiseworthy as any work in the 1970s.

Vocalist Dagmar Krause provides a stellar brilliancy the moment she takes over the vocals from Peter Blegard, four seconds into the album on “War,” which at 2:31 in length would have been perfect for radio play in some alternate universe — but alas our universe wasn’t quite up to the challenge of accepting irregularly contoured melodic phrases, asymmetrical time signatures, complex and politically charged lyrics, ominous incursions of harmonic instability, and the interspersion of harnessed chaos between vocal passages.

With the listener’s musical mind properly attuned, Henry Cow unleashes Tim Hodgkinson’s 16-minute “Living in the Heart of the Beast.” Initially, Peter Blegvad was asked to provide the lyrics, but ultimately Hodgkinson took over the task, crafting a set of syllables and meanings that seamlessly support the music. The work avoids any traditional structure, initially navigating shifts between vocal intensity and instrumental reflection until a wonderful organ solo introduces a forceful, uplifting instrumental interlude. This gives way to serious introspection from the organ, which then returns to the insistent, march-like vocal over metrical shifts, now irrevocably increasing in intensity until the coda winds down the work. Perhaps this may musically recall for some listeners the finale of ELP’s Tarkus as the wounded Tarkus retreats from the battlefield; however, in this case, the music is a call to charge into “fight for freedom,” providing a remarkable level of optimism and energy, effectively enveloping the listener in an afterglow as side one comes to a close.

Continuing the topic of marching to fight for freedom, side two opens up with “Beginning: the Long March”, an abstract, avant-garde representation of the march towards battle. It’s unstructured collage of electronic effects and musique concrète sensibilities may not appeal to the casual listener, but for someone focused on the overall flow and intent of the album this is a very appropriate and effective transaction to the next musical milestone, “Beautiful as the Moon; Terrible as an Army with Banners.”

This second track of side two, “Beautiful as the Moon; Terrible as an Army with Banners”, begins with Krause’s finely controlled, expressively nuanced delivery, dominating the first half with the entreaty to “seize the morning.” An instrumental commentary propels the start of the second half, with some excellent pointillistic contrapuntal piano punctuation with authoritative commanding vocals seizing the spotlight again to effectively close the work.

The last track, Morning Star, given its significance by the previous track’s lyrics of “A star mourns souls ungraved – ignored. Slow wheels: Mira. Algol. Maia” and “Rose Dawn Daemon Rise Up and seize the morning” brings the album to an effective close, firmly resolute and transcendent, firmly tying the album’s musical and verbal themes of awake, consider, prepare, engage and, ultimately, arrive and be!

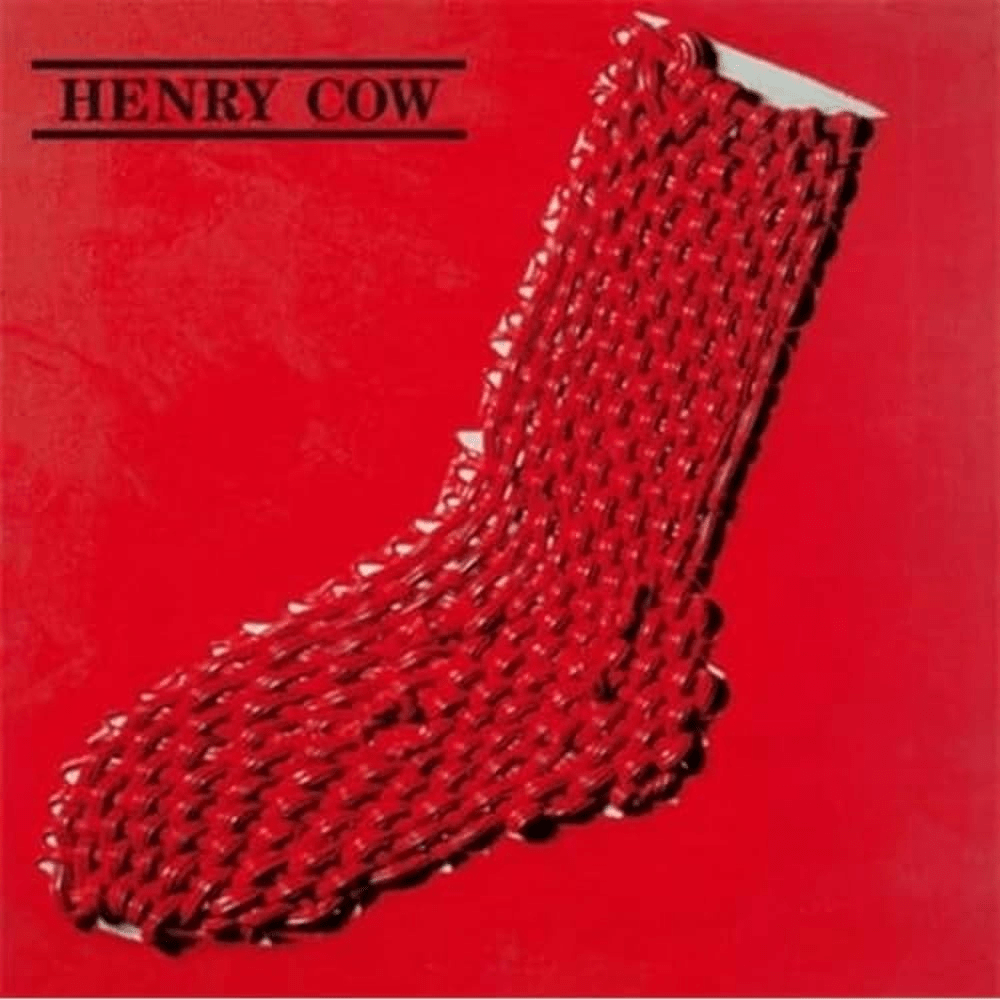

Robert Wyatt: Ruth Is Stranger Than Fiction

Robert Wyatt’s Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard, released in May 1975, is a strikingly unpredictable album, filled with angular compositions that shift direction almost from note to note. Unlike his previous two solo albums, which were composed entirely of his own material, this third album finds Wyatt showcasing the music of others, creatively arranging and in most cases adding lyrics. Most compositions are by Wyatt’s friends and musical associates, but Wyatt also provides a fine treatment of jazz bassist Charlie Haden’s “Song for Che.”

The album’s eclecticism is immediately apparent with a strong focus on jazz. Is this jazz-rock, jazz-prog-rock or mostly jazz? Not sure, but it is wonderful and a non-stop thrill from start to finish! The flow of the album never flirts with predictability, its angularity lending a sharp, dynamic energy that keeps the listener engaged.

With contributions from Brian Eno, trumpeter Mongezi Feza and Fred Frith on piano, Ruth Is Stranger Than Richard thrives on musical interplay and spontaneity. It’s a thrilling listen, bursting with invention, providing a richness of the unexpected without being disjointed or even mildly inaccessible. Wyatt’s vision is as playful as it is sophisticated, making this a truly exciting and engaging listening adventure.

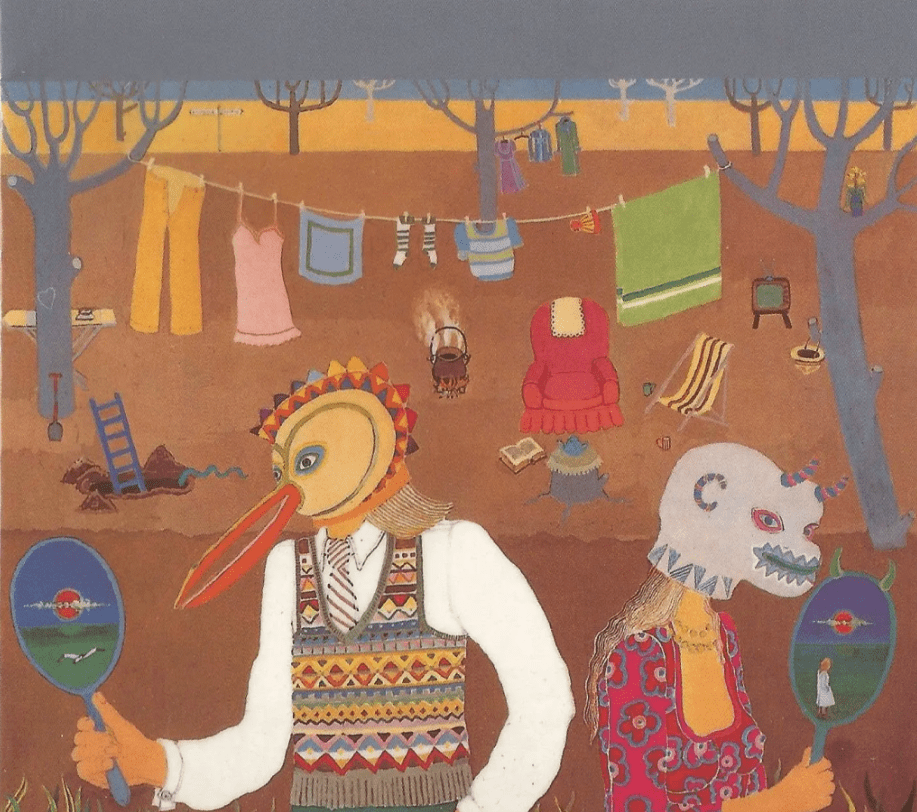

Weather Report: Tale Spinnin

Tales Spinnin’, released in May of 1975, is a vibrant, colorful album that showcases Weather Report at the height of their fusion creativity. The first side of the album is particularly striking, filled with bold, dynamic compositions that blend intricate melodies with rich textures. It is if I can almost hear colors when listening to this first side — it is that visually evocative, aurally. I wish I had some sophisticated color display screens for both the left and right channels that would translate the music into various bursts and evolving strands of colors, but lacking that, I can luxuriate in the radiant waves of Zawinul’s lush synthesizers and Wayne Shorter’s fluid, expressive saxophone work. The interplay between all five musicians is electric, creating a vivid musical landscape that’s both sophisticated and exploratory. The rhythms are complex yet accessible, propelling the tracks into lush, otherworldly soundscapes that are full of life and color.

Hawkwind: Warrior On the Edge of Time

Released on May 9. 1975, Hawkwind’s Warrior on the Edge of Time is both engaging and consistently accessible, effectively blending their signature space rock with more traditional prog-rock elements. There is strong emphasis on synthesizers with some effective flute, guitar and even violin to supplement the keyboards, thundering bass, and the often incessant forward-driving percussion. “Assault & Battery” begins the album in grand style, immediately immersing the listener in Hawkwind’s signature Space Rock. This album showcases Hawkwind at their peak, delivering a memorable, mythic sci-fi journey through the fabric of time and space rock.