Fifty Year Friday: August 1973

Henry Cow: Legend (Leg End, The Henry Cow Legend)

Henry Cow’s first album was released on August 31, 1973, with recording sessions in June and May. Like the Beatles’ White album, there is no visible title to the album, plus, the band’s name is not anywhere to be found on the front cover. Fortunately, the band name is on the back, with a list of tracks and credits (including who played what instrument), and more importantly the music is first class — an off-kilter, but exhilarating mixture of progressive rock and free jazz. It is as unique and important as Gentle Giant’s Power and the Glory, Yes’s Close to the Edge, Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick, and ELP’s Brain Salad Surgery, even though it lacks the consistency of quality. However, those tracks that are excellent on Leg End, and there are several, shine brightly and reach deeply into one’s musical soul.

Album starts off strongly with Fred Firth’s “Nirvana For Mice”, a playful, quirky and adventurous track, that starts of with some nuggets of catchy musical motifs and then opens up to some freely improvised jazz sax over a structured rhythmic and tonal foundation. I think it important to note, this is not free jazz, there is a structure in place, and this structure not only keeps the music accessible, but provides the proper foundation for the improvised parts to shine. Piece closes with a mixed meter fanfare, followed by a short vocal section.

The second track, “Amygdala”, written by Tim Hodgkinson, starts off with a pastoral tone that includes a calming, moss-covered mix of a beautiful, flowing blend of myriad instruments supported nicely by Firth’s jazz-style electric guitar with some acoustic flute from Geoff Leigh. We then get a sequence of passages that includes an exciting mixed-meter passage with some incredible musicianship, a lengthier, more reflective section, which brings us back to the pastoral and idyllic and transitions into a more propulsive section with some mixed meters and exciting accents, and then some alternation between the calm, reflective mood and the adventurous and exhilarating, with the piece ending in relative calm — punctuated by a concluding musical period.

The third track is all-out free-jazz, done well, even if not my cup of tea, and transitions nicely into the fourth track, “Teenbeat.” “Teenbeat” is another short masterpiece angular and compelling, unabashedly dancing over metrical microseisms. “Teenbeat” winds down nicely with contemplative clarinet commentary.

Side Two opens with a soothing and reflective composition by Firth titled “Extract from With the Yellow Half-Moon and Blue Star.” Its middle section evokes echoes of Messiaen, while the third section briefly hints at elements reminiscent of King Crimson. This section gracefully winds down, culminating in a slightly pensive coda. From there, it seamlessly launches into the upbeat and perpetually moving first section of “Teenbeat Reprise,” which, in turn, transitions to a quieter second section adorned with a livelier coda.

“The Tenth Chaffinch”, starts off as if picking up the more serene tone of the second section of “Teenbeat Reprise”, but that gradually dissolves into the more abstract, avante-garde personality of the composition, first with hints of finch bird whistles, and then, as best as I can make it, some reversed human dialogue, and then finishing with a bit of an art-rock avante-garde pastiche. Overall, this track is less interesting than their earlier free-jazz track, “Teenbeat Introduction”, but it is what it is, at least until it is rescued by the final track, “Nine Funerals of the Citizen King” with its literary refences and its sinewy melody — convincingly ending a very unusual, but fulfilling, musical journey.

Stevie Wonder: Innervisions

In 1973, like most teenagers, I had heard numerous AM hits by Stevie Wonder over the course of many years, but nothing resonated enough for me to purchase an album. That changed on a cruise to Hawaii with my parents on the Princess Italia cruise ship, a cozy, comfortably-sized cruise ship accommodating around 700 passengers with a cool movie theater, great dining and a modestly-sized nightclub where a four-piece band played a range of dance tunes. It was a perfect place to hang out until the midnight buffet was served, and then, after indulging in numerous tasty treats and multiple slices of pizza, return to for more dancing and drinks, at least for those of us over 17, or in that general neighborhood, as no one questioned birth dates or ages. The first night of dancing, the band played “Living For the City.” I didn’t know the name of it, or who wrote it, but I loved the synthesizer part, played by the band’s keyboardist, and the tune was great to dance to, and it was also the lengthiest of the rock tunes that they played. The last night on the ship, I asked the keyboard player for the name of the tune, and then once back in Southern California, bought Stevie Wonder’s Innervision, for the sole purpose of having access to “Living For the City.” As it turned out, Innervision was an exceptionally good album — my favorite track would continue to remain “Living For the City” but the albumAs it turned out, Innervisions proved to be an exceptionally outstanding album. “Living For the City” remained my favorite track, but the album as a whole creates a captivating forty-five-minute listening experience with superb arrangements and excellent engineering and mixing. makes for a great forty-five minute listening experience with overall superb arrangements, excellent engineering and mixing.

Can: Future Days

Can’s fourth studio album came out around August 1973, less experimental, but no less innovative than their previous three albums. There is a substantial difference in tone and style, with Future Days being a generally ambient, atmospheric work. Damo Suzuki’s vocals retreat into the instrumental gestalt, taking more of an instrumental role. That doesn’t keep me from trying to understand the words, as difficult as that task is, and then once understood, trying to interpret their meaning. But that is a diversionary activity when the real story here is the music, magically unfolding, ethereal and spellbinding.

The album begins with the title track, relaxing and calming, with “Spray” being more rhythmical, particularly at the start. The first side ends with Can’s attempt at a single, “Moonshake”, as groovy and laid back as a isolated spot on a Caribbean beach, not too distant from the flow and ebb of the tides with the sounds of distant birds and a Caribbean band intwined into our half-waking moments.

The masterpiece of the album is “Bel Air” which absorbs all of side two. The work moves forward with a German Prog-rock inevitability, within a more-or-less nebulous structure. The “more or less” qualifier is required due to the use of a traditional, though brief, catchy chord sequence occurring near the beginning and then later recurring at the end, providing a more traditional sense of form. Despite this, the work maintains a beautiful nebulosity, shimmering, reflectively and refractively, evolving in its nomadic passage.

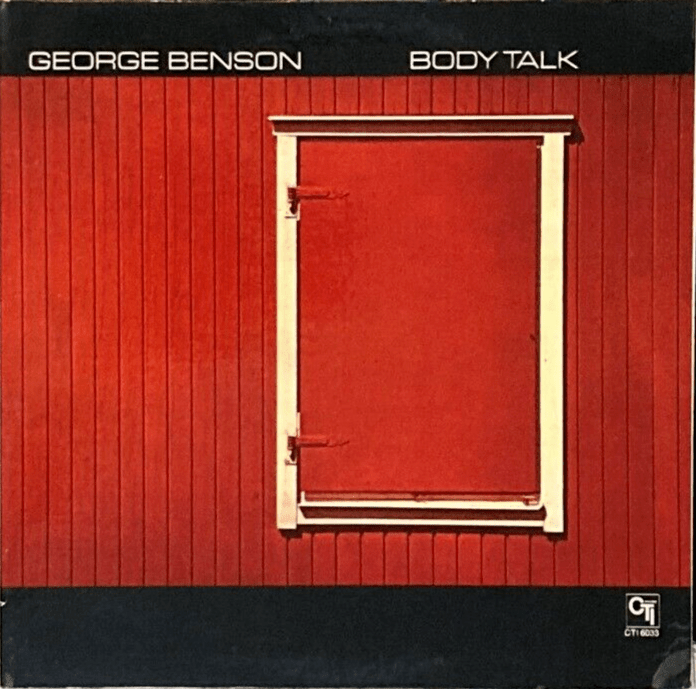

George Benson: Body Talk

Released August 23, 1973, George Benson’s twelfth studio album, Body Talk, is mostly a jazz-funk album, and a pretty good one. The opening track, “Body Talk” is historically notable as it, together with “Dance” influenced Michael Jackson’s “Wanna Be Startin’ Somethin.'” (Basically, it sounds as if it is these two tracks that provided the primary musical material for Jackson’s rhythmically vibrant song.)

Putting aside the jazz-funk material, the real highlight of the album are the two more traditional jazz tunes here, the elegantly beautiful “When Love Has Grown” with notable guitar work from both Benson and Earl Klugh, and the melodically-catchy “Plum” with solid ensemble work, some exciting, energetic guitar from Benson and distinguished solos from Frank Foster on sax and Harold Mabern on electric piano.