It’s not very difficult to make the case for Chopin being the greatest composer for the piano of the last 190 years. I chose 190 years, since Beethoven was around until 1827, and its irrelevant, and even irreverent, to compare Beethoven and Chopin. One can even make a good case for Chopin being the greatest Western composer of the last 190 years despite weaknesses and/or apparent lack of interest in mastering orchestration and writing pieces for full orchestras that go beyond providing general accompaniment for the piano.

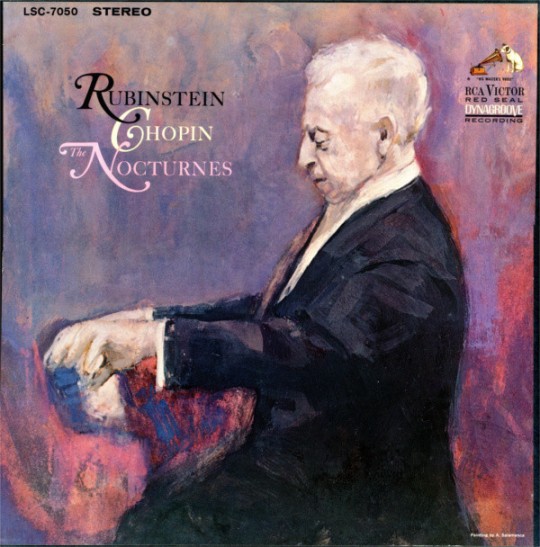

One can also make a good case for Arthur Rubinstein being the greatest Chopin performer of the Twentieth Century. In 1967, RCA released a 2 LP set of Rubinstein playing all the Chopin Nocturnes. All of these were recorded in 1965, except for Opus 55, No. 2 which was recorded in 1967. (Interesting, that is the only track that has notable distortion or harshness. For all the other nocturnes, the recording sound is quite good and provides an intimate, warm listening experience.)

What makes Rubinstein such a welcome interpreter of Chopin is that he doesn’t overemphasize the emotional nature of the music. Some performers go a bit to far in slowing down, speeding up, playing too loudly here, playing too softly there — trying to eke out as much emotion as possible. “Rubato” is the performing technique of slightly changing the notated rhythmic duration of notes, thus deviating from notes strictly aligning with their written place within the pulse of the rhythm. When done right the overall pace is not violated so that if a given note is made shorter, another note or other notes are then made longer so the one doesn’t lose the overall beat of the music. When overdone, rubato, along with accelerando (speeding up), rallentando (slowing down) and tenuto (holding on to notes for additional time) becomes a violation of the original spirit of the music, effectively remaking it into something akin to over-dramatic acting. Many performers, particularly in the first seventy years of the twentieth century, took extreme liberty with the music, stamping it with their own mark or as a means of pulling out inherent meaning in the music they felt was implied but not notated.

Rubinstein, who takes a relatively sober approach with Chopin, has so much control over which notes within chords or concurrent groups of notes get emphasized (and the general loudness or softness of each and every note he plays) that he can get a full range of emotions within even a strict tempo. His tempo, of course, is far from strict or mechanical, but he never allows it to escape into regions of extreme excess. Instead of taking unacceptable liberty with the tempo or individual note values, he makes the music sing and sparkle, providing a window into the inherent expression and delicate craft of each of these nocturnes: each one providing their own world of night-like expressiveness with subtle emotional twists and turns sometimes exploring sadness, loss, longing, darkness, tenderness, patience, determination, reflection, wistfulness, sympathy, sensitivity, sentimentality, loneliness, isolation, discovery, thoughtfulness, triumph, confusion or other emotions and aspects of the human psyche.

This recording is currently available as a 2 CD set, remastered and either in 16-bit or 24-bit (SACD) versions. Value-conscious consumers will be wise to opt for “The Chopin Collection” box set which is an 11 CD set with all these nocturnes, and all the mazurkas, waltzes, preludes, other solo piano music (minus the etudes), and as a bonus, the piano concertos — this entire set currently selling at under $24. Those with a larger budget and more available listening time may choose to get the much more expensive 142 CD “Arthur Rubinstein Complete Album Collection” set (with 2 DVDs and a 164 page booklet.)

Tracklist [from discorgs.org]

| A1 | Opus 9, No. 1 In B-flat Minor | |

| A2 | Opus 9, No. 2 In E-flat | |

| A3 | Opus 9, No. 3 In B | |

| A4 | Opus 15, No. 1 In F | |

| A5 | Opus 15, No. 2 In F-sharp | |

| B1 | Opus 15, No. 3 In G Minor | |

| B2 | Opus 27, No. 1 In C-sharp Minor | |

| B3 | Opus 27, No. 2 In D-flat | |

| B4 | Opus 32, No. 1 In B | |

| B5 | Opus 32, No. 2 In A-flat | |

| C1 | Opus 37, No. 1 In G Minor | |

| C2 | Opus 37, No. 2 In G | |

| C3 | Opus 48, No. 1 In C Minor | |

| C4 | Opus 48, No. 2 In F-sharp Minor | |

| D1 | Opus 55, No. 1 In F Minor | |

| D2 | Opus 55, No. 2 In E-flat | |

| D3 | Opus 62, No. 1 In B | |

| D4 | Opus 62, No. 2 In E | |

| D5 | Opus 72, Op. 72, No. 1 In E Minor |

Credits

- Composed By – Chopin*

- Piano – Arthur Rubinstein

- Producer – Max Wilcox

In my junior year of high school, with summer not too far off, one of my favorite people of all time, who I will just refer to with the initial “P”, and I were discussing music in the back of trig class and P. mentioned how good Pink Floyd was. The year was 1972 and I was probably talking about King Crimson, Yes, Jethro Tull, or ELP when P. started expressing his approval of Pink Floyd. I was interested and accepted his offer to lend me three of his albums, Ummagumma (1969), Atom Heart Mother (1970) and A Saucerful of Secrets (1968), finding many things I liked, but also finding several detours from what I considered the general flow of music. P. also, perhaps at a later point in time, lent me the first album, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” (1967). I was more pleased with that album then the others, and puzzled that this was the first album as it seemed the strongest to me, which was not the usual pattern that I saw for most groups where the first album was the weakest, the second better and the third or fourth finally being the break-out album. This first album, though sounding dated to my early 1970’s sensitivities, seemed stronger and more consistent than the other three I had previously heard. I am not sure if I had noticed that one musician, “Syd Barett”, was the composer of most of the music for the first album but was absent on the others. I think its possible I did realize this and was probably why I didn’t pay much attention to any new releases by Pink Floyd until I saw the movie “Pink Floyd at Pompeii” , at our local art-house theater, The Wilshire theater. This film captures Pink Floyd performing several selections of their music in an empty Pompeii amphitheater, the music completely enveloping and engaging. After seeing this, I was sold on Pink Floyd, and had I seen this a couple of years earlier, I would have listened much more intently to those albums my trigonometry classmate had lent me.

Looking back now with thousands of additional hours of listening to lots of different music, I can better appreciate this album much more than I ever could have at age sixteen. It doesn’t matter whether this is labeled art-rock, space-rock, psychedelic rock or something else: it is bold, original and relevant for 1967 and is still fun to listen to today.

The album borrows its title from a title of the seventh chapter of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows a cool title, indeed, but also a chapter that contains an interesting reference for a musical group that started out primarily as a psychedelic dance band:

“(Rat:) ‘…And hark to the wind playing in the reeds!’

`It’s like music–far away music,’ said the Mole nodding drowsily.

`So I was thinking,’ murmured the Rat, dreamful and languid. `Dance-music — the lilting sort that runs on without a stop — but with words in it, too — it passes into words and out of them again — I catch them at intervals — then it is dance-music once more, and then nothing but the reeds’ soft thin whispering.'”

And we have dance music with words and far-away lilting non-stop psychedelia-based tunes with their first two singles, written by Syd Barret, “Arnold Layne” and “See Emily Play” and their less dance-able, more exploratory, third single, “Apples and Oranges” also written by Syd Barrett.

And this album is filled with easily accessible dreamy, languid, melodic gems: these all written by Syd Barrett. The UK version (import version for us Americans) is different from a somewhat messed-up U.S. version (the version I will reference below is the superior UK version.)

“Astronomy Domine” is a masterpiece of space rock – vast, unfolding, hints of the infinite and timeless, paced with a relentless, cosmic inevitability, modal and chromatic.

“Lucifer Sam”, about a Siamese cat, is more whimsical but still edged with an embrace of psychedelia and a chromatic passage reminiscent of the James Bond theme.

“Matilda Mother” opens slow-paced, relaxed, and dreamy, shifting to a more rhythmic passage and then back to the dreamy opening before its short Indian-like instrumental — providing but short contrast to the returning dreamy theme and a brief instrumental coda.

While other groups at this time are starting to augment their music with strings, woodwinds, and exotic instruments, Pink Floyd achieves equally impressive results with a traditional line-up of vocals, guitar, bass, organ/piano and drums. Syd Barrett’s guitar, though not textbook virtuosic, is expressive, flexible and effective. Vocals include wind effects and bird calls, “oohs” and “aaahs”. The organ provides drones and other relatively simple effects. “Flaming” and the more free-form “Pow R. Toc H.” shows off the ability of the band to create very different soundscapes, the former showcasing guitar and organ, the latter, nicely showcasing piano, bass drums, guitar, simple vocal effects, and organ in various moods and attitudes with an almost jazz-like piano and drum interlude providing welcome contrast.

Roger Waters provides a very sixties contribution in the opening of “Take up Thy Stethoscope and Walk” which then dissolves into a group jam.

We get back to great music on side two with the opening of “Interstellar Overdrive”, though it does soon meander, losing focus — but better uncompromising and adventurous, than bland and commonplace: perhaps the band assumes the listener will have some assistance with illicit substances. Pretentious, often a term overused as an invective against progressive rock much more than psychedelic rock, is a term I am loathe to use — but I will concede that the ending is a bit over the top.

We get back to Barrett mini-masterpieces for the last four tracks. The music is unassuming, natural and foundationally simple. “Gnome” is pure pop, but with a Barrett twist. “Chapter 24” is spacey and reflective with lyrics apparently based on the 24th chapter of I Ching “The Return” (or “Turning Point”) as translated below by Richard Wilhelm:

“Everything comes of itself at the appointed time. This is the meaning of heaven and earth. All movements are accomplished in six stages, and the seventh brings return. Thus the winter solstice, with which the decline of the year begins, comes in the seventh month after the summer solstice; so too sunrise comes in the seventh double hour after sunset. Therefore seven is the number of the young light, and it arises when six, the number of the great darkness, is increased by one. In this way the state of rest gives place to movement”

Compare this to the Barrett lyrics:

“A movement is accomplished in six stages

And the seventh brings return.

The seven is the number of the young light.

It forms when darkness is increased by one.

Change returns success,

Going and coming without error.

Action brings good fortune:

Sunset.

“The time is with the month of winter solstice

When the change is due to come.

Thunder in the other course of heaven;

Things cannot be destroyed once and for all.

Change returns success,

Going and coming without error.

Action brings good fortune:

Sunset, sunrise.

“Scarecrow” opens up with some nifty percussive syncopation upon which the melody is overlaid, giving us a short song that’s simple and complex simultaneously.

“Bike” magnificently ends this album with more hazy, dreaming psychedelia based on simple melody and chords effectively arranged and presented. This is a perfect conclusion to a very different album than anything else in 1967 popular music.

After listening to this album, and looking at the song credits, one might very well conclude that Syd Barrett was the key member of Pink Floyd and without them they would either struggle as a band or be very different and probably not nearly as good. Without getting into the tragedy of Barrett’s behavioral disorders, likely an after-effect of repeated LSD usage, which is covered by numerous resources on the web including Wikipedia and several WordPress blogs (most of which are generally much better written than this one), the band soon dropped an unreliable and unpredictable Syd Barrett from their line-up. Barrett continued to struggle from the aftermath of chemically-caused neurological damage, subsequently recording two solo albums in 1969, and then more or less becoming a recluse until his death in 2006 at the age of 60. From such a promising first album ensues an heart-sickening tragedy; just another instance of a unconventional, creative genius taken away from us in the turbulent, unpredictable, ever-changing 1960s.

Track listing [from Wikipedia]

UK release

| Side one | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | “Astronomy Domine“ | Syd Barrett | Syd Barrett and Richard Wright | 4:12 |

| 2. | “Lucifer Sam“ | Barrett | Barrett | 3:07 |

| 3. | “Matilda Mother“ | Barrett | Barrett and Wright | 3:08 |

| 4. | “Flaming“ | Barrett | Barrett | 2:46 |

| 5. | “Pow R. Toc H.“ |

|

instrumental | 4:26 |

| 6. | “Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk“ | Waters | Roger Waters | 3:05 |

| Total length: | 20:44 | |||

| Side two | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | “Interstellar Overdrive“ |

|

instrumental | 9:41 |

| 2. | “The Gnome“ | Barrett | Barrett | 2:13 |

| 3. | “Chapter 24“ | Barrett | Barrett | 3:42 |

| 4. | “The Scarecrow“ | Barrett | Barrett | 2:11 |

| 5. | “Bike“ | Barrett | Barrett | 3:21 |

| Total length: | 21:08 | |||

US release

| Side one | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | “See Emily Play“ | Barrett | Barrett | 2:53 |

| 2. | “Pow R. Toc H.” |

|

instrumental | 4:26 |

| 3. | “Take Up Thy Stethoscope and Walk” | Waters | Waters | 3:05 |

| 4. | “Lucifer Sam” | Barrett | Barrett | 3:07 |

| 5. | “Matilda Mother” | Barrett | Barrett and Wright | 3:08 |

| Side two | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocals | Length |

| 1. | “The Scarecrow” | Barrett | Barrett | 2:11 |

| 2. | “The Gnome” | Barrett | Barrett | 2:13 |

| 3. | “Chapter 24” | Barrett | Barrett | 3:42 |

| 4. | “Interstellar Overdrive” |

|

instrumental | 9:41 |

Personnel

Pink Floyd

- Syd Barrett – lead guitar, vocals

- Roger Waters – bass guitar, vocals

- Richard Wright – Farfisa Combo Compact organ, piano, celesta (uncredited), vocals (uncredited)

- Nick Mason – drums, percussion

Production

- Syd Barrett – rear cover design

- Peter Bown – engineering

- Peter Jenner – intro vocalisations on “Astronomy Domine” (uncredited)

- Vic Singh – front cover photography

- Norman Smith – production, vocal and instrumental arrangements, drum roll on “Interstellar Overdrive”[125]

Previous Fifty Year Friday Posts:

Comments on: "Fifty Year Friday: Arthur Rubinstein “Chopin: The Nocturnes, Pink Floyd “Pipers at the Gates of Dawn”" (7)

Interesting pairing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

VC,

Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I seem to recall writing somewhere that the Floyd were working on this at Abbey Road at the same time that the Beatles were there creating Sgt Pepper and that there was (or probably was) some influence/inspiration. Unfortunately I can’t remember in which direction this (or might have) flowed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, Ben. Abbey Road was the studio they used for this album. They, of course, spent less studio time than the Beatles did. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Inspiration only requires a second though. It’s the fahioning of its expression that takes the time. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

thanks for sharing all this! I have not heard his music, only his name! I will love to!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sharmishtha,

Thanks! Worth checking out, for sure!

LikeLike